Introduction

Atherosclerosis (AS) is a complex and chronic inflammatory disease, which is considered as one of the most common vascular diseases [1, 2]. Oxidative stress is a common mediator in the pathobiology of risk factors for cardiovascular disease [3], and endothelial cell injury caused by oxidative low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) is usually characterized as an early marker for AS [4]. Recent reviews have shown that ox-LDL is mainly taken up by macrophage scavenger receptors, which trigger pro-inflammatory cytokine release and further cause endothelial cell dysfunction [5, 6].

Recently, accumulating proof indicates that the long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) function as pivotal regulators in diseases [7, 8]. Meanwhile, numerous lncRNAs were identified to be involved in the physiology and tumourigenesis. For example, lncRNA ZEB1-AS1 was identified as a cancerogenic regulator in cancer progression [9]. It is currently considered to be a crucial cancer-related lnc-RNA. It was observed to be highly expressed in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma [10], osteosarcoma [11], bladder cancer [12], glioma [13], colorectal cancer [14], and B-lymphoblastic leukaemia [15]. Li et al. summarized current evidence concerning the ZEB1-AS1 in the form of tables. The combined data show that ZEB1-AS1 acts as either a tumour inhibitor or as a carcinogen during tumourigenesis. However, the function and regulatory mechanism underlying ZEB1-AS1 in ox-LDL-induced endothelial cells still need further investigation.

In addition, non-coding RNAs, including lncRNA and microRNAs (miRNAs), play crucial roles in the occurrence and progression of cancer by regulating several physiological and pathological processes [16]. LncRNA are longer than 200 nucleotides in length, while miRNA as endogenous small RNA consists of 18-24 nucleotides. LncRNA acts as a competitive endogenous RNA to interact with miRNA [17, 18]. Both of these play a crucial regulatory role in the complex mechanisms of cancer development [19].

In a previous study, ZEB1-AS1 played a role in ox-LDL-induced endothelial cell damage [20]. On the basis of the above findings, in order to explore ZEB1-AS1/miR-590-5p underlying the molecular relationship in ox-LDL-treated endothelial cell damage, the effects of the ZEB1-AS1/miR-590-5p/HDAC9 axis on ox-LDL-mediated endothelial cell proliferation and apoptosis were investigated.

Material and methods

Samples and ethics statement

Blood samples were obtained from 30 normal persons and 30 AS patients in Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University. Serum was obtained from the blood after standing overnight at 4oC, and then stored at –20oC until total RNAs were extracted. This protocol was authorised by the Ethical Committee of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, and all patients gave written informed consent.

Cell culture and ox-LDL treatment

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were obtained from the Bena Culture Collection (Suzhou, Jiangsu, China). At 37°C and 5% CO2, HUVECs were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) and 1% antibiotics (Gibco). Ox-LDL (UnionBiol, Beijing, China) was purchased and diluted to different concentration gradients. HUVECs were incubated with increasing concentrations of ox-LDL (0, 25, 50, 100 µg/ml) for 24 h or at different points in time (0 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h) at the concentration of 50 µg/ml, and then a quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assay was utilized to estimate the level of ZEB1-AS1 and miR-590-5p in HUVECs.

qRT-PCR reaction

Total RNA from serum samples or cells was extracted using TRIzol (Takara, Dalian, China) and transcribed into cDNA via FastQuant RT reagent (Takara), and qRT-PCR was conducted with SYBR Green I Kit (Takara) on an ABI 7500 HT system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). All data were normalized to U6 or GAPDH. The relative expression of genes was calculated using the 2-△△Ct method [21]. The main primer sequences for qRT-PCR were as follows: ZEB1-AS1, forward, ATTTGAATTGAGGGGCGAGG and reverse, GGAAACCAGGCGTCCCTTT; U6, forward, CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA and reverse, AACGCTTCACGAATTTG; HDAC9, forward, AGTAGAGAGGCATCGCAGAGA and reverse, GGAGTGTCTTTCGTTGCTGAT; GAPDH, forward, GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC and reverse, ATGGTGGTGAAGACGCCAGT. Besides, Silencing RNA sequences were as follows: si-ZEB1-AS1#1, GACCGGAGUAUUGGAAAUA; si-ZEB1-AS1#2, GGGCACUGCUGAAUUUGAA; si-ZEB1-AS1#3, GCUGAAGUCUGAUGAUUUA; si-NC, GACCTACAACTACCTATCA.

Cell transfection

Interference fragment of ZEB1-AS1 (si-ZEB1-AS1#1, si-ZEB1-AS1#2, si-ZEB1-AS1#3), miR-590-5p inhibitor (anti-miR-590-5p), overexpression of HDAC9 (pcDNA-HDAC9), and their negative controls (si-NC, anti-miR-NC, or pcDNA) were received from RiboBio (Guangdong, China). HUVECs were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and induced by ox-LDL (100 µg/ml) for the later experiments.

MTT assay

HUVECs were grown after ox-LDL induction in a 96-well flat-bottomed plate. MTT solution was added into cell culture wells and incubated with cells for 4 h at a temperature of 37oC. The upper media was taken away, and then DMSO was utilized to dissolve formazan crystals. Finally, the absorbance of cells was determined at 490 nm. All assays were conducted more than 2 times.

Annexin V/PI double-staining assay

HUVECs were grown and exposed with the indicated concentrations of ox-LDL. After a certain period of time, cells were harvested and then stained with annexin V-FITC and PI. The apoptosis rates of cells were evaluated by flow cytometry (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and analysed using software. Each assay was performed 3 times.

Western blot assay

Well-grown cells were treated with ox-LDL. Total protein extraction was performed via RIPA buffer (Pierce, Rockford, USA). Protein was segregated by SDS-PAGE after quantification, and then transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The blots were incubated with primary antibodies against tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) (1 : 200, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), cleaved caspase-3 (1 : 1000, Abcam), cleaved PARP (1 : 1000, Abcam), or GAPDH (1 : 2000, Abcam, UK), and then added with secondary antibody (1 : 5000, Abcam). Finally, the signal was detected via an ECL Plus Detection kit (Pierce).

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

The binding sites of ZEB1-AS1 and miR-590-5p were predicted by StarBase v2.0. The potential target HDAC9 of miR-590-5p was searched with TargetScan. The wild-type or mutant ZEB1-AS1 (ZEB1-AS1-wt and ZEB1-AS1-mut) and HDAC9-3’UTR (HDAC9-wt and HDAC9-mut) fragments were constructed and inserted into pMIRGLO™ luciferase vectors (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Ox-LDL-treated HUVECs were cotransfected with above plasmids and miR-590-5p or miR-NC by using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen). Then, luciferase activity was detected via Dual-Luciferase Assay Kit (Promega).

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay

To attest the relationship between ZEB1-AS1 and miR-590-5p, an RIP assay by EZ-Magna RIP kit (Millipore) was used. Briefly, ox-LDL-treated HUVECs were obtained and resolved in RIP lysis buffer. Next, the cell lysates were incubated with protein A/G bead-conjugated anti-Argonaute2 (Ago2) antibody (Abcam) or control immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody (Abcam) at 4°C for 4 h. Finally, co-precipitated RNA was measured by qRT-PCR analysis.

Results

ZEB1-AS1 was upregulated in AS patient serums and ox-LDL-treated HUVECs, the opposite of miR-590-5p

In order to explore the relationship between genes expression levels in the serums of normal persons and patients the levels of ZEB1-AS1 and miR-590-5p and ox-LDL treatment dose or treatment time were studied. The ZEB1-AS1 level was increased in AS patient serums relative to that of normal persons (Fig. 1A), which was accompanied by dose-dependent ox-LDL-induced endothelial cell injury. The expression level of ZEB1-AS1 was the highest at 100 µg/ml, compared to other concentrations (Fig. 1B). Similarly, ZEB1-AS1 was upregulated in a time-dependent fashion after ox-LDL-challenged injury of endothelial cells at the concentration of 100 µg/ml (Fig. 1C). Moreover, a reduced miR-590-5p level was shown in AS patients (Fig. 1D), and miR-590-5p abundance was lowered followed by the addition of incremental concentration of ox-LDL treatment in HUVECs (Fig. 1E), as well as the ox-LDL treatment time in HUVECs (Fig. 1F), which was exactly the opposite of the expression trend of ZEB1-AS1. The results indicated that the ox-LDL concentration of 100 µg/ml should be used for further experiments. Hence, HUVECs that treated with 100 µg/ml ox-LDL for 24 h were employed as an in vitro cellular model for AS in subsequent research.

Fig. 1

Expression of ZEB1-AS1 and miR-590-5p in the serum of AS patients and ox-LDL-treated HUVECs. A, D) The levels of ZEB1-AS1 and miR-590-5p were detected by qRT-PCR in AS patient serums. B) HUVECs were treated with 0, 25, 50, and 100 μg/ml ox-LDL for 24 h. C) HUVECs were treated with 100 μg/ml ox-LDL for 0, 12, 24, and 48 h. E, F) Ox-LDL treatment decreased miR-590-5p expression in a dose- or time-dependent manner. *p < 0.05

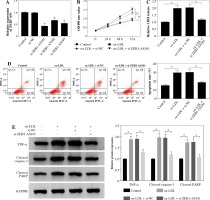

Knockdown of ZEB1-AS1 promoted ox-LDL-treated HUVEC proliferation and inhibited HUVEC apoptosis

To explore the potential character of ZEB1-AS1 in ox-LDL-induced HUVEC injury, the HUVECs were treated with ox-LDL for 24 h at 100 µg/ml. ZEB1-AS1 was silenced by using 3 specific silencing oligonucleotides (si-ZEB1-AS1#1, si-ZEB1-AS1#2, and si-ZEB1-AS1#3) in HUVECs. The qRT-PCR results demonstrated that the abundance of ZEB1-AS1 was significantly downregulated compared with negative controls after si-ZEB1-AS1#1 transfection (Fig. 2A); thereby, it was utilized for subsequent study. MTT assay indicated that ZEB1-AS1 silence promoted ox-LDL-treated endothelial cell proliferation (Fig. 2B). ZEB1-AS1 interference overtly overturned the accelerated effect of ox-LDL addition on LDH liberation (Fig. 2C). Flow cytometry results showed that knockdown of ZEB1-AS1 inhibited HUVEC apoptosis (Fig. 2D). In addition, western blot assay showed that the levels of TNF-α, cleaved caspase-3, and cleaved PARP were significantly downregulated after ZEB1-AS1 silencing (Fig. 2E). These data suggest that knockdown of ZEB1-AS1 facilitated the proliferation of endothelial cells induced by ox-LDL and inhibited endothelial cell apoptosis in vitro.

Fig. 2

ZEB1-AS1 silencing promoted ox-LDL-treated endothelial cell proliferation and inhibited endothelial cell apoptosis. A) ZEB1-AS1 was silenced by transfection of specific ZEB1-AS1 siRNAs (si-ZEB1-AS1#1, si-ZEB1-AS1#2, and si-ZEB1-AS1#3). B, C) HUVECs (treated with ox-LDL or not) were transfected with si-NC or si-ZEB1-AS1#1. Cell viability (B) and LDH release (C) were measured by MTT assay and LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit, respectively. D) HUVEC apoptosis was detected after treatment with ox-LDL or knockdown of ZEB1-AS1 for 24 h. E) The protein levels of TNF-α, cleaved caspase-3, and cleaved PARP were measured in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs transfected with si-ZEB1-AS1#1. *p < 0.05

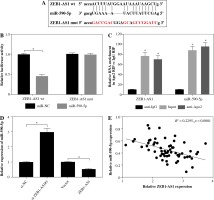

MiR-590-5p was targeted by ZEB1-AS1 in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs

Considering the opposite expression of ZEB1-AS1 and miR-590-5p in the ox-LDL-treated HUVECs, we speculated that ZEB1-AS1 and miR-590-5p may have a targeted relationship. As expected, Starbase software showed that ZEB1-AS1 had complementary sequence with miR-590-5p (Fig. 3A). Luciferase reporter results showed that miR-590-5p visibly lessened the luciferase expression of ZEB1-AS1-WT in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs but did not affect that of ZEB1-AS1-MUT (Fig. 3B). RIP assay suggested that ZEB1-AS1 and miR-590-5p were both particularly enriched in HUVEC extracts of Ago2 group compared to that of the IgG group (Fig. 3C). The level of miR-590-5p was distinctly raised after ZEB1-AS1 knockdown, and ZEB1-AS1 overexpression inhibited miR-590-5p expression levels (Fig. 3D). The abundance of ZEB1-AS1 and miR-590-5p had a significant negative correlation (Fig. 3E). Collectively, these findings hinted that ZEB1-AS1 could directly bind to miR-590-5p and served as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA).

Fig. 3

miR-590-5p is a direct target of ZEB1-AS1 in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs. A) The predicted binding sites of miR- 590-5p in ZEB1-AS1. B) Luciferase activity was detected in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs cotransfected with luciferase vectors containing ZEB1-AS1-wt or ZEB1-AS1-mut and miR-NC or miR-590-5p. C) RIP assay was conducted in ox- LDL-treated HUVECs extracts to examine miR-590-5p endogenously associated with ZEB1-AS1. D) The expression of miR-590-5p in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs transfected with si-NC, si-ZEB1-AS1#1, Vector or ZEB1-AS1 was detected by qRT-PCR assay. E) The negative correlation between ZEB1-AS1 and miR-590-5p in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs (R2 = 0.2295, p = 0.0001). *p < 0.05

ZEB1-AS1 silencing attenuated ox-LDL-induced endothelial cell injury through regulation of miR-590-5p

Inhibition of ZEB1-AS1 could significantly increase miR-590-5p expression, while inhibition of miR-590-5p could significantly mitigate the effect of the ZEB1-AS1 knockdown (Fig. 4A). MTT assay showed that ZEB1-AS1 silencing promoted ox-LDL-induced endothelial cell proliferation (Fig. 4B) and decreased the release of LDH. While ZEB1-AS1 was knocked down, miR-590-5p silencing could abolish these effects (Fig. 4C). ZEB1-AS1 silencing attenuated ox-LDL-induced apoptosis of endothelial cells through regulation of miR-590-5p (Fig. 4D). In addition, knockdown of ZEB1-AS1 inhibited TNF-α, cleaved caspase-3, and cleaved PARP protein levels (Fig. 4E). The data indicate that ZEB1-AS1 silencing attenuated ox-LDL-induced endothelial cell damage via regulation of miR-590-5p.

Fig. 4

ZEB1-AS1 silencing attenuated ox-LDL-induced endothelial cell injury through regulation of miR-590-5p. After treatment with ox-LDL, the HUVECs were transfected with si-NC, si-ZEB1-AS1#1, anti-NC, or anti-miR-590-5p + si- ZEB1-AS1#1. A) The expression levels of miR-590-5p were detected by qRT-PCR. B) The viability of ox-LDL-induced HUVECs was detected at the indicated time points by MTT. C) Relative LDH release of ox-LDL-induced HUVECs was analysed by ELISA. D) The apoptosis of HUVECs were detected by using flow cytometry. E) The TNF-α, cleaved caspase-3, and cleaved PARP protein expressions were measured by western blot analysis. *p < 0.05

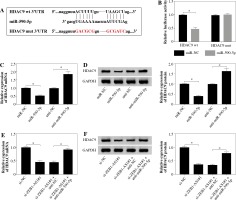

ZEB1-AS1 regulated HDAC9 expression via miR-590-5p

TargetScan suggested that 3’UTR of HDAC9 contained with the miR-590-5p seed sites, and the bases of the binding site sequence were mutated (Fig. 5A). To evaluate the direct binding between miR-590-5p and HDAC9, dual-luciferase reporter assay was implemented. It was certified that miR-590-5p observably decreased the luciferase activity of HDAC9-wt plasmid (p < 0.05) but had no effect on that of HDAC9-mut plasmid (Fig. 5B). Next, qRT-PCR and western blot assay showed that HDAC9 was strongly downregulated after miR-590-5p transfection in HUVECs and was upregulated after miR-590-5p interference in mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 5C, D). MiR-590-5p inhibition partially reversed the effects of ZEB1-AS1 knockdown on HDAC9 expression of ox-LDL-treated HUVECs (Fig. 5E), as well as HDAC9 protein expression levels (Fig. 5F). All data indicate that ZEB1-AS1 regulated HDAC9 expression by targeting miR-590-5p.

Fig. 5

ZEB1-AS1 targeted miR-590-5p to regulate HDAC9 expression. A) The predicted binding sites of miR-590-5p in 3’-UTR of HDAC9. B) The wild-type or mutated HDAC9 3’-UTR reporter plasmids were co-transfected into ox-LDLinduced HUVECs with miR-NC or miR-590-5p, and then luciferase activity was detected. C, D) Expression levels of HDAC9 mRNA and protein were examined by qRT-PCR (C) and western blot (D) in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs treated with miR-NC, miR-590-5p, anti-NC, or anti-miR-590-5p, respectively. E, F) Expression levels of HDAC9 mRNA and protein were examined by qRT-PCR (E) and western blot (F) in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs treated with si-NC, si-ZEB1- AS1#1, si-ZEB1-AS1#1 + anti-NC, and si-ZEB1-AS1#1 + anti-miR-590-5p, respectively. *p < 0.05

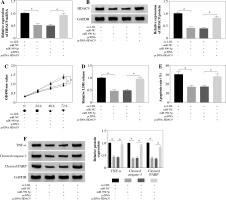

HDAC9 reversed the influence of miR-590-5p on proliferation and apoptosis of ox-LDL-induced endothelial cells

To explore the functional relationship between miR-590-5p and HDAC9 in ox-LDL-induced endothelial cells, the expression of HDAC9 was measured in HUVECs after miR-590-5p overexpression and pcDNA-HDAC9, respectively. As presented in Figure 6A, B, miR-590-5p overexpression dramatically repressed expression of HDAC9 in mRNA and protein levels; however, this effect was evidently improved by HDAC9 overexpression. Furthermore, HUVECs were cotransfected with miR-590-5p mimics and pcDNA-HDAC9 to investigate their roles in cell progression. MTT assay demonstrated that overexpression of miR-590-5p overtly enhanced ox-LDL-induced HUVEC proliferation (Fig. 6C). Relative LDH release was decreased in HUVECs after overexpression of miR-590-5p (Fig. 6D), whereas HDAC9 supplement relieved these effects. Meanwhile, the apoptosis of HUVECs transfected with pcDNA-HDAC9 vector was dramatically increased compared with control groups (Fig. 6E). In addition, the introduction of miR-590-5p triggered an evident reduction in TNF-α, cleaved caspase-3, and cleaved PARP expression in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs, and pcDNA-HDAC9 reversed the above effects (Fig. 6F). These data suggest that HDAC9 reversed the impact of miR-590-5p on proliferation and apoptosis of ox-LDL-induced endothelial cells.

Fig. 6

HDAC9 reversed the effect of miR-590-5p on proliferation and apoptosis of ox-LDL-induced endothelial cells. After treatment with ox-LDL, the HUVECs were transfected with miR-NC, miR-590-5p, pcDNA, or pcDNA-HDAC9. A, B) The expression levels of HDAC9 mRNA and protein were detected by qRT-PCR and western blot analysis, respectively. C, D) Cell viability and LDH release were measured by MTT assay and ELISA, respectively. E) HUVEC apoptosis was detected by using flow cytometry assay. F) The TNF-α, cleaved caspase-3, and cleaved PARP protein expression were measured by western blot analysis. *p < 0.05

Discussion

Recently, the causal mechanisms of AS development have been explored by more and more researchers. According to previous studies, lipid metabolism disorder is the basis of AS lesions. Moreover, ox-LDL-mediated endothelial cell injury is a crucial factor in the development and progression of AS [22, 23]. AS is an inflammatory disease [24, 25]. It is the primary cause of coronary heart disease, cerebral infarction, and peripheral vascular disease, which are among the leading causes of disease death in the world today [26]. Therefore, it is highly important to inspect the mechanism of ox-LDL-induced endothelial cell injury.

Emerging studies suggest a crucial regulatory effect of lncRNAs in human diseases, particularly in tumourigenesis. For example, the lncRNA MALAT1 level was significantly higher in patients with unstable angina and could protect the endothelium from ox-LDL-induced endothelial dysfunction [27]. LncRNA CCAT1 was also up-regulated in colorectal cancer and was considered as a detectable marker for early detection of colorectal cancer [28]. Studies have shown that lncRNA XIST is upregulated in ox-LDL-mediated HUVECs, and knockdown of XIST alleviates ox-LDL-mediated endothelial cell injury [29]. Therefore, it is necessary to exploit more lncRNAs and target genes and illuminate their underlying mechanism in the development of cancers.

ZEB1-AS1 has been identified as an oncogenic regulator during the occurrence and development of diverse malignancies. Originally, differentially expressed ZEB1-AS1 was identified and investigated in hepatocellular carcinoma [30]. Meanwhile, different splicing variants of ZEB1-AS1 were explained in different cell lines [31]. More importantly, ZEB1-AS1 as a transcription factor functions in the development of cancers [32]. Recently, more and more attention has been paid to the functional roles of ZEB1-AS1 in ox-LDL-mediated endothelial cell injury.

Significant roles of miRNA in AS have been studied. miR-590-5p has been shown to keep endothelial cells from ox-LDL-induced apoptosis by regulating LOX-1 expression [33]. Based on animal models of AS, miR-590 suppressed ox-LDL-induced apoptosis in HAECs through inhibition of the TLR4/NF-κB pathway [34]. In this study, ZEB1-AS1 was increased in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs, the opposite of miR-590-5p, and relative expression of ZEB1-AS1 and miR-590-5p had a negative correlation. Further studies indicated that ZEB1-AS1 knockdown enhanced ox-LDL-treated endothelial cell proliferation and inhibited endothelial cell apoptosis, and attenuated ox-LDL-treated endothelial cell injury through regulation of miR-590-5p. Bioinformatics software predicted that miR-590-5p and HDAC9 have targeted binding sites. Previous studies showed that HDAC9 played regulatory roles in ox-LDL-induced endothelial cell inflammation [35]. HDAC9 was differently up-regulated in endothelial cells [36]. The deletion of HDAC9 could reduce the occurrence of inflammation and AS [37]. Previous reviews indicated further roles of HDAC9 in AS and inflammation [38]. Therefore, we speculated the roles of HDAC9 may be involved in endothelial cell damage. In agreement with previous findings, the results in this study showed that HDAC9 reversed the effect of miR-590-5p on proliferation and apoptosis of ox-LDL-induced endothelial cells.

This study showed that ZEB1-AS1 regulated HDAC9 expression by affecting miR-590-5p expression in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs. However, a deeper inquiry of whether ZEB1-AS1/miR-590-5p/HDAC9 signalling affects the activation of certain pathways associated with endothelial cell injury will be a subject of our further research.

Conclusions

We identified the targeting correlation between lnc-RNA ZEB1-AS1 and miR-590-5p by establishing a model of ox-LDL-induced endothelial cell injury. Moreover, our results further attested that ZEB1-AS1 silencing alleviates ox-LDL-induced endothelial cell damage by regulating the miR-590-5p/HDAC9 signalling axis, which might be a novel strategy to target therapy of endothelial cell injury in AS.