Purpose

Lip cancer is a rare malignancy among the global population, with an incidence of 0.3 cases per 100,000 per year [1,2]. There are regions where a number of cases are higher than average. It may be linked to sun exposure, combined with specific skin phenotype (e.g., Spain, Australia) or with increased consumption of tobacco and alcohol (e.g., Central and Eastern Europe) [1]. Other factors include male sex and low level of education. The decrease in the incidence of lip cancer may be associated with educational activities, an increase of self-consciousness, and a drop in tobacco use in the last 20 years [1,2]. Ninety-five per cent of lip malignancies are squamous cell carcinomas [3].

Radical surgery, with or without lymphadenectomy, is the first choice and gold standard of treatment [4,5,6,7,8,9]. However, if surgery is subtotal (i.e., positive or close margins), which is not unusual, there is a need for adjuvant irradiation to decrease the risk of a recurrence [10,11]. Recommendations for adjuvant treatment following non-radical lip cancer surgery seem to be imprecise. Positive margins or perineural invasion are mentioned as the indications for irradiation; a panel of experts issued no opinion on close margins proceedings, but they added that every squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) case should be treated individually [5,10,12].

There are data available on brachytherapy regarding the treatment of lip cancer [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21, 22,23]. Results reported in these studies are encouraging, with five-year local control of 77-100%, and mostly good cosmetic outcomes and no grade 4 late toxicities. However, these publications analyzed heterogeneous groups of patients, with either primary tumors, local relapses, or after non-radical surgery, treated with low-dose-rate brachytherapy (LDR-BT), pulse-dose-rate brachytherapy (PDR-BT), or high-dose-rate brachytherapy (HDR-BT). There is no recommendation on adjuvant brachytherapy after surgical excision. Interstitial PDR-BT is preferred for lip cancer management in our center. We aim to analyze the efficacy and toxicity of adjuvant PDR-BT retrospectively after insufficient surgery in the management of lip cancer.

Material and methods

Twenty lip cancer patients, with a median age of 66.5 years (range, 45-94 years) were treated from January 2012 to September 2016. There were three women and 17 men in the analyzed group. Most of them had lower lip (95%) involvement. Primary treatment included surgery with or without reconstruction, 75% and 25%, respectively. Moreover, 70% of patients underwent neck dissection. Either bilateral lymphadenectomy (40%; with suprahyoid bilateral neck dissection, 35%) or selective neck dissection (30%) were performed. All patients were diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma, while most of the tumors were pT1 (60%, according to UICC/AJCC TNM version 7, 2009). One patient had micrometastasis in a node of IA group. Patients were qualified for adjuvant PDR-BT due to positive or close post-operative margins (< 5 mm). Patients characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

Patients characteristics

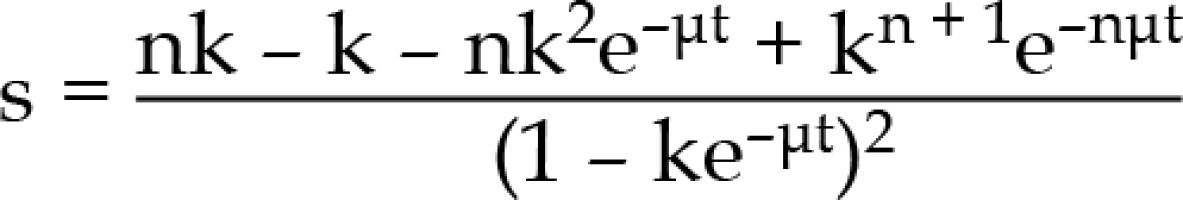

Brachytherapy procedures were completed after post-operative wound healing (median of 62 days; range, 40-96 days). Plastic catheters (flexible implant tubes by Nucletron, an ELEKTA company, ELEKTA AB, Stockholm, Sweden) were implanted, with insertion needles into the tumor bed under local anesthesia in the operating theatre. Median of three plastic tubes were implanted (range, 1-5). A free-hand technique was used. After the implantation, computed tomography scanning without contrast was done, with maximum slices of 1.2 mm (Figure 1). Treatment planning was completed the OncentraBrachy system (Nucletron, an ELEKTA company, ELEKTA AB, Stockholm, Sweden). Two PDR-BT treatments with two separate implantations were scheduled for every patient, with a gap of median 13 days (range, 6-17 days). Patients were connected to microSelectron PDR (Nucletron, an ELEKTA company, ELEKTA AB, Stockholm, Sweden) afterloader (192Ir stepping source, with nominal activity 1 Ci) for whole treatment session and could be disconnected on demand between pulses. The presence of physician and qualified nurse on the ward during the procedure was required, but their presence in the afterloader control room was not – the patient was continuously observed via audio-visual system. The planned dose was 0.8-1 Gy per pulse to total dose from two PDR-BT treatments of 50 Gy. A physician defined clinical target volumes (CTV) after every implantation (median, 3.95 ml; range, 1.4-12.83 ml), which was a scar with margins adapted to the initial tumor volume, location, and pathological report; the total margin of surgery and PDR-BT should be at least 1 cm. The transversal plane was used for catheters reconstruction. Source step was 2.5 mm, while no active positions were allowed outside the CTV. An initial plan was prepared with inverse planning simulated annealing algorithm for dwell time deviation constraint of 0.3. In the next step, the treatment plan was graphically optimized by a physicist. A final plan was chosen according to 90% isodose coverage of CTV (D90) and volumes of 100% and 150% isodoses (V100, V150). Maximal dose and volume of 200% isodose were reported. Maximal dose on the skin surface (Dmax skin) was investigated retrospectively for this analysis.

Fig. 1

Axial, coronal, and sagittal view, and 3D reconstruction of computed tomography-based treatment plan for adjuvant PDR-BT of lip cancer. Four interstitial applicators were inserted with free-hand technique

Eleven patients (55%) received 1 Gy per pulse and four patients (20%) 0.8 Gy per pulse, while for five patients (25%), 1 Gy per pulse was prescribed for the first PDR-BT and 0.8 Gy per pulse for the second treatment due to logistic reasons. Every treatment contained 25 to 32 pulses, given every 50-60 minutes. Median total dose from two fractions was 50 Gy (range, 49.8-50.6 Gy). Utilizing α/β = 10 Gy and sublethal damage repair halftime T1/2 = 1 h for squamous cell carcinoma for early effects, and α/β = 3 Gy and T1/2 = 1.5 h for late effects biologically effective dose (BED) formula were used to compare scheduled doses and dose-volume parameters (Table 2):

Table 2

Achieved dose parameters for interstitial pulse-dose-rate brachytherapy (PDR-BT)

[i] D90 BED 10 – dose covering 90% of CTV calculated for α/β = 10 (early tox/tumor cells), PD BED 10 – planed physical dose calculated for α/β = 10 (early tox/tumor cells), Dmax skin BED 10 – maximum dose reported in skin calculated for α/β = 10 (early tox/tumor cells), D90 BED 3 – dose covering 90% of CTV calculated for α/β = 3 (late tox), PD BED 3 – planed physical dose calculated for α/β = 3 (late tox), Dmax skin BED 3 – maximum dose reported in skin calculated for α/β = 3 (late tox)

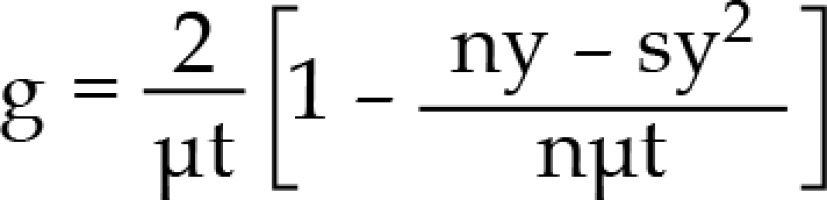

BED = nd [1 + dg/(α/β], where

n – number of pulses, d – pulse dose, α, β – coefficients determining the death of cells as a result of the passage of one or more radiation quanta, g – repair function

k = e–μx , y = 1 – e–μt, where

μ - repair constant (In/T1/2), t – pulse time, x – time between pulses

No shields were used during the treatment. Patients were discharged after catheters removal. First follow-up visit was planned four weeks after the treatment and then, patients were evaluated every 3-6 months. Follow-up time was counted from the last day of treatment to the last control visit in our center. Early and late toxicities were assessed with RTOG scale after clinical examination. The intensity of acute adverse-events was evaluated until the first visit, while late events were defined as occurring four months after PDR-BT.

Statistical analysis

Data was collected in a spreadsheet (MS Excel). Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 12.0 (StatSoft, Inc. Tulsa, USA). Students unpaired t-test was applied to determine the significance of the differences for continuous variables between the two-sample means. The Mann-Whitney test was used for ordinal and continuous variables without normal distribution. DFS survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Statistical significance was considered if p-value was lower than 0.05.

Results

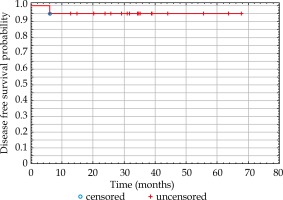

Average follow-up was 34.7 months (median, 34.5 months; range, 12.7-67.6). Local control at last follow-up was 100%. There was no difference between three- and five-year estimated disease-free survival, which was 95% (Figure 2). One patient suffered from regional relapse in the submental region (IA lymph node group). The same patient was diagnosed with micrometastasis in the pathological examination after the neck dissection; however, due to the extension of the surgery, multi-disciplinary tumor board resigned from adjuvant elective radiotherapy to the neck lymph nodes.

Fig. 2

Kaplan-Meier curve of disease-free survival (DFS) probability after adjuvant brachytherapy of the lip cancer

Acute toxicity was grade 2 or below. Skin erythema or dry desquamation (grade 1) or wet desquamation (grade 2) were observed in 13 patients (65%) and one patient (5%), respectively. Six patients presented no acute toxicity. Moreover, there were no complications involving lip mucosa.

All patients had grade 1 soft tissue fibrosis in the irradiated area, besides that, late toxicity included only skin complications: five patients (25%) reported grade 1 depigmentation, three patients (15%) had mild telangiectasia (grade 2), and two patients suffered from skin ulceration (grade 4). The female patient had diagnosed systemic lupus erythematosus a few months after PDR-BT was finished. The male patient denied medical recommendations during and after PDR-BT; he also was a heavy smoker. Both cases were treated successfully with surgical excision.

There were no significant factors associated with skin late toxicity ≥ grade 2; however, a tendency was observed for higher Dmax skin BED3. Statistical analysis is presented in Table 3.

Table 3

Comparison of skin late toxicity G < 1 and skin late toxicity G > 2 factors

| Factors | Late toxicity G < 1 (n = 15) | Late toxicity G > 2 (n = 5) | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | SD | Mean | Median | SD | ||

| Age (years) | 66.5 | 66 | 10.3 | 65.2 | 72 | 14.6 | 0.76† |

| Time from surgery (months) | 66.9 | 64 | 17.4 | 58.6 | 54 | 13.5 | 0.35§ |

| D90 BED 3 (Gy) | 118.3 | 117 | 18.5 | 126 | 125 | 57.3 | 0.4§ |

| PD BED 3 (Gy) | 117.4 | 121 | 4.9 | 114.6 | 115 | 11.7 | 0.38† |

| Dmax skin BED3 (Gy) | 279 | 244 | 124.5 | 404.4 | 408 | 6.5 | 0.12† |

| V100 (cc) | 3.85 | 3.0 | 2.58 | 2.64 | 1.7 | 166.26 | 0.28+ |

| V150 (cc) | 2.08 | 1.7 | 1.21 | 1.48 | 1.0 | 1.71 | 0.32§ |

| V200 (cc) | 1.15 | 1.1 | 0.62 | 0.82 | 0.5 | 0.82 | 0.24† |

| Follow-up (months) | 35.6 | 34.3 | 17.3 | 31.9 | 34.7 | 4.4 | 0.64§ |

Discussion

Even though interstitial brachytherapy is invasive, this irradiation technique seems to be favorable for patients with lip cancer [22]. Due to brachytherapy dosimetric advantages and high conformity, it is eligible for local treatment [24,25,26].

Our study confirmed that interstitial PDR-BT for patients after non-radical lip cancer surgery is efficient and safe. It is in agreement with other brachytherapy studies; however, data on adjuvant brachytherapy in lip cancer management are scarce and limited. Grabenbauer et al. presented head and neck cancer patients treated with adjuvant LDR-BT [14]. Although investigated group included 318 patients diagnosed with oral cavity or oropharynx cancer (a primary or a recurrent tumor; staged from I to IV), only 19 patients (6%) suffered from lower lip cancer. Similarly, Strnad et al. showed large head and neck cancer patient group of 385 patients treated with PDR-BT, but only 19 (3.6%) patients suffered from lip cancer [15]. Ten patients (11%) had adjuvant LDR-BT due to positive margins (6 patients) or relapse after surgery (4 cases), among 89 lip cancer patients described by Rio et al. [16]. In a study, Guinot et al. [17] presented results of a cohort including 102 patients with lip cancer, out of which, twenty cases (20%) were treated with post-operative HDR-BT. Johansson et al. reported long-term results of PDR-BT in the management of lip cancer in 43 patients, but only 11 patients (26%) were treated because of positive margins [18].

Despite the heterogeneous groups comprising either primary or adjuvant approach, the efficacy of post-operative brachytherapy is excellent. Our results showed 100% local control at last follow-up. Patients from other studies had a similar outcome. Large PDR-BT head and neck study showed no significant differences between anatomical sites, with local control of 86% estimated for 5 years [15]. Another PDR-BT study presented 5-year local control of 95% after median follow-up of 54 months (telephone interviews included) [18]. Loco-regional failure (second head and neck tumor, no lip recurrence) was observed in one (2%) post-operative PDR-BT patient. Also, LDR-BT showed its efficiency, with at least 77% of 5-year local control in combination with external-beam radiotherapy [14]. The same study reported 5-year local control of 89% for post-operative brachytherapy alone. A different study on LDR-BT in lip cancer estimated 100% local control after five years, but all patients treated with excision combined with brachytherapy were staged as T1 [16]. HDR-BT study demonstrated 100% local control after a median follow-up of 45 months; however, two nodal relapses were observed in this group [17].

The GEC-ESTRO recommends interstitial brachytherapy for primary lip cancer treatment [22]. The 2017 update of the GEC-ESTRO ACROP recommendations advise the use of brachytherapy also in the adjuvant option for head and neck tumors, but without any suggestions for dose scheduling [27]. While the interstitial insertion of catheters was consistent among reported groups, treatment schedules varied. Physical prescribed doses are hard to compare, particularly among PDR-BT, LDR-BT, and HDR-BT [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,21]. Nevertheless, biologically effective doses were between 57-73 Gy (tumor α/β = 10 Gy), which was similar to our group (median, 65 Gy; range, 62-65 Gy). Patients assessed in this paper received total physical dose between 49.8-50.6 Gy, which was less than reported PDR-BT patients (range, 55-57 Gy) [15,18]. However, similar BED was achieved with higher pulse doses, 0.8-1 Gy every 1 hour versus 0.55 Gy/h or 0.834 Gy every 2 hours, even though efficacy and side effects were comparable. Evaluation of available brachytherapy regimens are summarized in the Table 4.

Table 4

Comparison of the lip cancer adjuvant sole brachytherapy regimens used in published literature

| n | Dose rate | Prescribed dose [Gy] | Schedule | OTT (days) | BED [Gy] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grabenbauer et al. [15] | 19 | LDR | 50-60 | 0.5 Gy/h | 4-5 | 57.1-68.6 |

| Strnad et al. [16] | 14 | PDR | 55* | 0.55 Gy/pulse/1 h | 4.2 | 63.9* |

| Rio et al. [17] | 6 | LDR | 58* | 1 Gy/h | 2.5 | 73.8* |

| Guinot et al. [18] | 20 | HDR | 40.5-45 | 9 fractions (4.5-5 Gy) | 5 | 58.7-65.2 |

| Johannson et al. [19] | 11 | PDR | 55-60 | 0.834 Gy/pulse/2 h | 5.5-6 | 62.6-68.3 |

| Present group | 20 | PDR | 50* | 0.8-1.0 Gy/pulse/1 h in 2 implants | 14* | 65* |

Interstitial brachytherapy as a local adjuvant treatment yields mild toxicity with good cosmetic results. In our group, 90% of patients developed late side effect of grade 2 and below. This is comparable with other PDR-BT groups. Severe complications were reported in 2 up to 10% of lip cancer and head and neck cancer patients [15,18]. Also, some LDR-BT and HDR-BT studies showed low toxicity, with no grade 4 late complications [16,17]. Other LDR-BT head and neck cancer study reported 7.5% of persistent ulcers, with or without osteonecrosis [14].

These results show that even patients with close margins (i.e., < 5 mm) should be considered as candidates for PDR-BT due to its low toxicity and short treatment time. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s (NCCN) recommendations of minimal margins of 5 mm in the surgical management of lip cancer are based on two publications [5]. Although both presented worse outcome for surgical patients with margin < 5 mm, one (Looser et al.) presented only two lip cancer patients in the 62 head and neck cancer patients group, while other (Scholl et al.) investigated tongue cancer patients only [11,28]. Moreover, the NCCN recommends that locally advanced lip cancer (> pT2) should be treated with adjuvant radiotherapy, according to Babington et al. [5,10]. This retrospective analysis reported 130 patients with lip cancer (96% ≤ pT2) divided into three groups. Patients were treated with surgery alone (51 patients), radiotherapy alone (62 cases), or a combination of surgery followed by radiotherapy (17 patients). Positive or close margins (≤ 2 mm) were reported in 27% of patients treated with surgery alone, and 96% in the group of combined treatment. The loco-regional failure was presented after surgery or its combination with radiotherapy in 53% and 6% of patients, respectively. Authors concluded that minimal margins should exceed 2 mm, with ideal margins of 4-5 mm, but if this goal is not achieved, adjuvant radiotherapy can provide an excellent local control.

As mentioned above, the evidence on the adjuvant lip cancer brachytherapy is limited. One of the most significant problems is small patients’ groups reported in larger datasets including primary tumors and/or other head and neck patients. Moreover, recommendations do not contain guidelines who, how, and when should be treated after lip cancer surgery with interstitial brachytherapy. This should be addressed in a modern digital approach with the use of data collection systems. One of these is the Consortium for Brachytherapy Data Analysis (COBRA), which is used by the GEC ESTRO Head and Neck Working Group [29,30].

Conclusions

PDR-BT in the adjuvant treatment of lip cancer yields high local control with low toxicity. It is advisable to pay significant attention in using maximum dose to the skin; it may be linked to higher complications probability. Although further studies with larger groups of patients are required, digital tools as the COBRA may be used to find guidelines and recommendations required.