Purpose

Locoregional recurrence (LRR) of head and neck cancer (HNC) is a major obstacle to long-term survival in this group of patients. While the introduction of immunotherapy has offered a new treatment modality with promising results for a cohort of patients [1], the standard of care for LRR in previously irradiated patients has traditionally been (whenever feasible) salvage surgery with or without external beam re-irradiation [2,3,4,5]. However, the decision to re-irradiate patients after salvage surgery remains controversial due to limited improvement in overall survival and associated risks of vascular events and osteoradionecrosis [6,7]. An alternative means of re-irradiating these patients is with permanent interstitial low-dose-rate (LDR) brachytherapy, which involves placement of radioactive seeds directly into the tumor bed at the time of resection, or with high-dose-rate (HDR) brachytherapy, where catheters are placed surgically and remain in place for a number days for treatment [8,9,10]. Unlike external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), brachytherapy is able to deliver a high-dose of radiation to the target area with relative preservation of normal tissue due to lower photon energy and associated rapid dose falloff [11]. Permanent interstitial brachytherapy is performed at the time of resection, and is advantageous over HDR brachytherapy; the catheters do not remain in place for a number of days and an additional procedure to remove them is not required. Proxcelan cesium-131 (131Cs) seeds (IsoRay, Richland, WA) have an average photon energy of 30 keV and a relatively short half-life of 9.7 days [12]. Patients treated with 131Cs have comparable rates of survival to those treated with EBRT, with decreased rates of radiation-associated toxicities [13].

Carotid blowout syndrome (CBS) occurs in approximately 2.6% of patients re-irradiated with EBRT after LRR of HNC, and is fatal in 76% of instances [14]. In patients re-irradiated with EBRT, there is no significant association between the maximum dose of radiation to the carotid and the risk of CBS [15]. The relationship between dose-volume parameters and risk of CBS in patients treated with permanent interstitial brachytherapy for recurrent HNC is unknown. Radiation dose-volume data for the carotid and CBS incidence data are presented for re-irradiated patients using 131Cs permanent implant brachytherapy.

Material and methods

We report on a cohort of patients enrolled in a 131Cs clinical trial approved by an institutional review board studying the safety and efficacy of 131Cs brachytherapy in the treatment of locoregional recurrent HNC.

Initial diagnosis and treatment

Nine patients were initially diagnosed with biopsy-proven squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, and two patients (6 and 11) were diagnosed with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Eight out of these eleven patients underwent surgical resection of the initial tumor and all were treated with EBRT, with an average total prior dose of 68.5 Gy (range, 26-130 Gy). Patient 10 received two prior courses of EBRT: 70 Gy and 60 Gy. Table 1 describes the initial diagnosis, staging, and treatment for each patient.

Table 1

Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients

| Patient | Age/gender | Previous diagnosis | Previous treatment | Time from EBRT to 131Cs (months) | Recurrence | Flap | Tumor adherent/non-adherent to carotid | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNM staging | Location | Surgery | EBRT dose (Gy) | ||||||

| 1 | 58/F | T2/N2b/M0 | Tonsil | Yes | 60 | 6 | Regional | Posterior digastric flap | Non-adherent |

| 2 | 68/M | T2/N2c/M0 | Supraglottis | Yes | 70 | 40 | Regional | None | Adherent |

| 3 | 69/M | T2/N2a/M0 | Nasopharynx | No | 70 | 76 | Regional | Pectoralis flap | Adherent |

| 4 | 48/M | T4/N2c/M0 | Oropharynx | No | 68 | 4 | Locoregional | ALT** free flap | Adherent |

| 5 | 57/M | T4a/N0/M0 | Base of tongue | Yes | 70 | 24 | Regional | ALT** free flap | Adherent |

| 6 | 46/F | T1/N3/M0 | Nasopharynx | No | 70 | 2 | Regional | None | Non-adherent |

| 7 | 69/F | T2N0M0 | Oral cavity oropharynx | Yes | 60 | 16 | Regional | Pectoralis flap | Adherent |

| 8 | 53/F | Tx/N2a/M0 | Unknown primary | Yes | 26 | 83 | Regional | None | Non-adherent |

| 9 | 48/F | T3/N2b/M0 | Base of tongue | Yes | 60 | 9 | Regional | Strap muscle rotational flap | Non-adherent |

| 10 | 66/M | T3/N2c/M0 | Hypopharynx, larynx | Yes | 70, 60* | 194, 10* | Regional | None | Non-adherent |

| 11 | 69/M | T3/N2/M0 | Nasopharynx | Yes | 70 | 43 | Local | Temporo-parietal fascia flap | Non-adherent |

Surgery and cesium brachytherapy implantation

All patients in this study were a part of a larger clinical trial investigating the benefit of cesium brachytherapy for previously irradiated patients. Inclusion criteria for this trial included a history of previous EBRT with treatment failure, ineligibility for re-irradiation with external beam based on the participating institution’s treatment paradigm, and age range 18-90. The average time from completion of previous EBRT to 131Cs implant was 28 months (range, 2-83 months). Patient 10 underwent two courses of EBRT 194 and 10 months prior to 131Cs implant. Between 2015 and 2018, these 11 patients underwent salvage surgery with a neck dissection as well as maximal gross resection of the tumor bed and concurrent placement of 131Cs brachytherapy seeds in the soft tissue of the neck per institutional protocol, as described previously by To et al. [16]. Tumor was adherent to carotid in five out of eleven patients (Table 1). In these patients, the carotid artery was skeletonized. In select cases, vascularized flaps were harvested to bring radiation-naïve tissue to the previously irradiated site and/or facial elements of the flap were placed between the carotid artery and the brachytherapy seeds to limit radiation exposure to the carotid. Table 1 lists the type of flap used for each patient.

Dosimetry calculation and uncertainty estimation

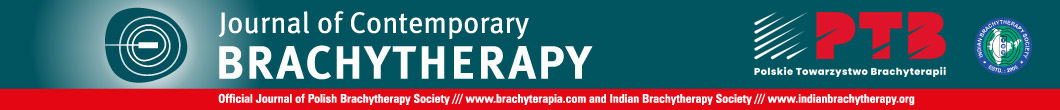

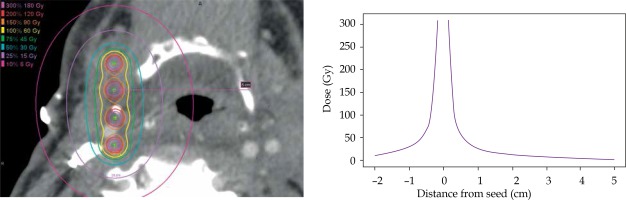

Pre-implant dosimetry was performed to estimate the number and air kerma strength of seeds required to deliver the prescribed dose to the estimated resection cavity [17]. All patients received a post-implant computed tomography (CT; slice thickness, 0.7-2.0 mm) on a Philips Brilliance 64 or iCT 256, using O-MAR artifact reduction when available. Post-implant dosimetry was performed by identifying the location of each implanted seed on the post-implant CT using MIM Symphony LDR™ brachytherapy dose calculation software (version 6.7, Cleveland, OH, USA), as seen in Figure 1A [18]. A point-dose model following the American Association of Physicists in Medicine’s TG-43 dose calculation formalism was used [19]. Details of the pre- and post-implant dosimetry are described in another publication [17]. Inter-seed attenuation effects were not included in the dose calculation [20]. The ipsilateral carotid or bilateral carotids for patient 10, whose implant was located midline, was identified and contoured on axial slices at least 1 cm above and below the implant on the post-implant CT by the attending radiation oncologist and surgeon. In cases where the carotid was difficult to visualize on post-implant CT, the carotid was contoured on a pre-implant contrast CT or an magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The pre-implant image was fused to the post-implant CT using rigid image registration in MIM, focusing on the volume in close proximity to the carotid and implant to ensure accuracy of the fusion in the area of interest. The contour was transferred onto the post-implant CT according to the registration. The minimum distance between the carotid and an implanted seed was recorded. Dose-volume parameters including the maximum dose received by 1 mm3 of the carotid over the lifetime of the implant, Dmax, and the dose to 0.1 cm3, 1 cm3, and 2 cm3 were recorded. To account for high levels of variability in reported Dmax due to uncertainties in contouring and/or image registrations, the carotid contours were isotropically expanded and contracted by 0.5 mm, and the dose-volume parameters to these structures were recorded. The dose fall-off gradient close to the seeds is extremely steep; for carotids located closer to the seeds, even small variations in the contour will yield marked variability in Dmax values. The dose fall-off from a sample implant is illustrated in Figure 2.

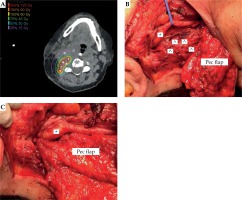

Fig. 1

A) Post-implant dose calculation for (B) intraoperative cesium implantation (^) adjacent to carotid (*). C) Pectoralis (Pec) major flap with interposition of thin facial element between carotid and cesium. Muscle bulk of the flap utilized to reconstruction skin and soft tissue of the neck

^ Cesium seed, *carotid artery

Follow-up and toxicity assessment

Follow-up visits were scheduled every three months in the two-year post-operative period. Patients were assessed at the time of visit for evidence of disease recurrence and radiation toxicity. The primary outcome of CBS was assessed retrospectively.

Statistical methods

The mean and standard deviation of the prescribed dose, seed activity, and minimum seed-carotid distance are reported to describe the implant characteristics of the cohort. The mean, standard deviation, and range of the following dose-volume parameters are reported: Dmax, 0.1 cm3, 1 cm3, and 2 cm3. All evaluable patients were included in the study and we present the following case series without power calculation.

Results

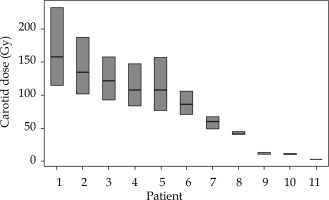

The average 131Cs dose was 57 ±5.7 Gy (range, 40-60 Gy) prescribed to 5 mm perpendicular from the center of the implant plane. The implanted seed activity was 2.3 ±0.4 U (range, 1.7-3.0 U). The average distance of the seed closest to the carotid artery was 0.8 ±0.8 cm (range, 0.2-2.6 cm), and the average maximum point dose, Dmax, to the carotid was 77 ±52 Gy (range, 3-158 Gy). The doses to 0.1 cm3, 1 cm3, and 2 cm3 were 39 ±23 Gy (range, 2-78 Gy), 19 ±10 Gy (range, 0-36 Gy), and 12 ±8 Gy (range, 0-27 Gy), respectively. This value corresponds to 135% of the average prescription dose. The carotid dosimetry and uncertainty results are presented in Figure 3. Details of the seed implants are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Dosimetric properties for each patient implant including number and activity of implanted seeds, prescribed dose, minimum seed-carotid distance, and the doses to 1 mm3 (Dmax), 0.1 cm2, 1 cm2, and 2 cm2 of the carotid artery. For the dose-volume parameters, the specified number is the estimated dose to the carotid contour, and the numbers in parentheses are the doses to the contracted and expanded carotid contours

Fig. 3

The center bar in each box is the maximum point dose to the carotid, Dmax. The upper and lower extends of the boxes are the Dmax values to the structures obtained by expanding and contracting the carotid isotropically by 0.5 mm. Expansion and contraction yields a much larger deviation in dose in the high dose region due to the steep dose gradient close to the seeds

Only one patient in the series (patient 10) experienced CBS eight months after implant. In this patient, the closest 131Cs seed was located 1.5 cm from the ipsilateral carotid artery and the Dmax to the carotid was low (12 Gy, 20% of the prescription dose). This patient had received two previous courses of EBRT and also elected not to undergo flap coverage of the 131Cs implant. Over the course of six months, wound breakdown occurred in this patient. The soft tissue of the neck proceeded to regress despite local wound care, including vacuum placement and wet to dry dressing changes. The patient refused further surgical intervention. Ultimately, the soft tissue receded over six months, leaving the carotid artery exposed. CBS in this patient was therefore attributed not to the relatively low-dose of radiation from the 131Cs seeds, but rather to wound breakdown.

Discussion

These results demonstrate that small volumes (1 mm3) of the carotid artery can safely be exposed to relatively high doses of radiation from 131Cs permanent brachytherapy. Although our case series was small (n = 11), the radiation dose and the distance between implanted seeds and the carotid artery demonstrate a safe toxicity profile with a wide variety of Dmax. Prior studies have shown that in patients re-irradiated with EBRT, the rate of CBS was approximately 2.6% [14]. As we look at the efficacy of various techniques of re-irradiation in this difficult cohort of patients, we need to account for safety.

The accuracy of the reported carotid doses depends on the correctness of post-implant dosimetry plan as well as the user’s ability to identify and contour the carotid artery. The post-implant dosimetry plan is created by manually identifying the center of each implant seed on an artifact-reduction CT scan; accuracy is limited by the slice thickness in the CT and can be challenging due to streaking artifacts caused by high-density surgical clips and drains. There is also uncertainty in contouring the carotid due to limited resolution of the CT, image artifacts, and poor contrast between the carotid and surrounding tissues. Uncertainty and resulting intra- and inter-observer variability of delineation of structures in the head and neck region is not unique to 131Cs brachytherapy and has been previously reported [21]. In cases where the carotid is close to the seeds, the dose gradients are extremely steep, and even a very subtle change (0.5 mm) to the contour boundary can result in dosimetric differences of 47% of Dmax. The dramatic dose gradients close to the seeds are illustrated in Figure 2. Maximum carotid doses are presented in Table 2 as a stated dose and then a range of doses resulting from expanding and contracting the carotid contour by 0.5 mm, in order to present a more realistic range of possible doses accounting for uncertainty in carotid contouring. Patients with seeds closer to the carotid exhibit larger dose uncertainty ranges because the dose gradient is steeper close to the seeds.

Contouring the carotid artery was performed based solely on the post-implant CT for nine of 11 patients. For two patients, the carotids were contoured on the pre-implant scan, and transferred to the post-implant scan based on the image registration. For both cases, the contours were adjusted minimally to align with calcifications in the vessels visible in the post-implant scan.

It is our opinion that the use of non-irradiated vascularized tissue should be considered when planning surgical implantation of 131Cs. Placing a 5 mm portion of fascia between seeds and vessels can control the radiation dose to the carotid or other organs at risk. Furthermore, the use of radiation-naïve tissue can promote wound closure and prevent catastrophic wound breakdown. As presented in patient 10, wound breakdown led to inadequate coverage of the carotids over six months resulting in carotid artery blowout. The carotid artery of this patient was exposed to markedly less radiation than the carotids of the patients who did not experience CBS. It was a delayed secondary sequela.

Conclusions

Small volumes of the carotid artery were exposed to relatively high doses during re-irradiation of recurrent HNC using 131Cs permanent implant brachytherapy. One patient in our series who did not receive a flap, experienced a carotid blowout. The use of flap coverage should be considered on a case-by-case basis to bring radiation-naïve tissue to the site, promote wound healing, and limit radiation dose to surrounding critical structures.