Point-of-care ultrasonography is increasingly incorporated into daily practice. Although the importance of bedside echocardiography in the intensive care unit (ICU), also known as critical care echocardiography (CCE), is widely accepted, there are few national guidelines [1] on the required competencies [2–5], and the accreditation process [6]. Competencies for CCE were established over a decade ago by the European Society and Intensive Care Expert Panel [3] and the World Interactive Network Focused on Critical Ultrasound (WINFOCUS) [7], but barriers still exist regarding implementation in clinical practice.

The aim of this survey is to provide the most up-to-date information regarding barriers to implementation of critical care ultrasound (CCUS) in daily practice. This information could then be used to suggest novel approaches to overcome such barriers, ultimately facilitating the wider integration and utilization of point-of-care echocardiography.

METHODS

The SurveyMonkey hosting platform was used to collect anonymous responses. Volunteers were asked to complete a 23-item questionnaire (Appendix); most variables were discrete in nature. Participants gave “consent by participation” by joining the survey, ensuring confidentiality and voluntary participation. The survey was designed in alignment with the checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys (CHERRIES). No incentives were offered. The study was endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM).

We conducted a pilot survey on ten clinicians of different nationalities (United Kingdom, Italy, and Poland) and backgrounds (consultant, trainees, anaesthesiologists, and intensive care physicians) to ensure completeness of the survey and no errors in the skip logic function (see later). These participants were asked to provide feedback on aspects of the survey questionnaire such as structure, ease of use and survey length. The time for survey completion and the responses were analysed using SurveyMonkey.

Design

The first section of the questionnaire contained six demographic items to differentiate the survey population based on their country of practice, the training received and the type of workplace.

To estimate the prevalence of general ultrasound use in critical care, we included questions about ultrasound use for different applications such as central line placement, lung ultrasound, and focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST). We also evaluated the availability of ultrasound machines with echocardiography capability, and we asked about the ability to perform bedside echocardiography and acquire basic cardiac views. Participants who provided a negative response were taken directly to the final part of the survey on limitations to the training and implementation of CCE; those providing a positive response continued to the sections describing experience in CCE and its clinical applications. The section on clinical applications was based on competences in basic CCE defined by a consensus statement [11]. The last section of the survey was about limitations and barriers.

Data collection

Questionnaires were distributed to participants via email with the support of the ESICM and of national societies that agreed to disseminate the survey to their mailing list. The participants received two reminders to complete the survey. Subsequently, the survey was also distributed via social media (Facebook and Twitter). The survey period was March 2021 to December 2021. Concurrently, a separate questionnaire was sent via email to 31 CCE experts from 14 countries, selected on the basis of authorship of consensus statements and recommendations on the use of CCE [7–10].

Statistical analysis

The demographics were characterised using descriptive statistics. The normality assumption was verified using the Shapiro-Wilk test and normal quantile plots. Normally distributed data are presented as mean and standard deviation; otherwise data are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR).

RESULTS

Demographics

644 responses were recorded in the survey, and as shown in Table 1 most responses were from Italy 23% (n = 148), Poland 18.8% (n = 121) and the UK 9% (n = 58). Most participants were dually trained in anaesthesia and intensive care 79% (n = 468), with most working in the ICU, 52% (n = 328). Young intensivists (trainees and those within 5 years after specialization) represented 56% (n = 358) of respondents. Two-thirds of respondents 66% (n = 414) selected a large university hospital as their primary institution, with over half of these participants reporting that they worked in a centre with over 40 specialists and trainees within the department, 36% (n = 228).

Equipment

A majority (92%, n = 594) had access to an ultra-sound machine with a cardiac probe available, and 97% (n = 623) of respondents reported being familiar with general ultrasound use for central lines, regional blocks, and lung ultrasound.

Echocardiography competencies

80% of respondents (n = 511) indicated some experience in bedside CCE which was self-judged as sufficient to acquire basic cardiac views.

Competencies

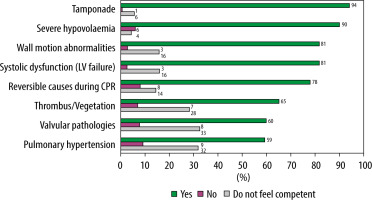

Most respondents were able to address basic questions on CCE: suspicion of tamponade, 94% (n = 434); presence of severe hypovolemia, 90% (n = 413); left ventricular systolic dysfunction, 81% (n = 376); wall motion abnormalities, 81% (n = 377); and reversible causes during cardiopulmonary resuscitation, 78% (n = 357) (Figure 1).

Barriers

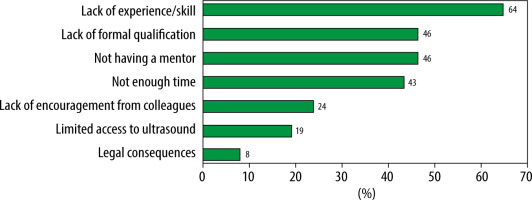

The most common barrier to the implementation of echocardiography in practice was the lack of experience/skill, 64% (n = 343) (Figure 2).

Experts survey – demographic data

We sent an additional questionnaire to 31 experts in the field of CCE and received a total of 28 responses. Most experts were intensivists: 50% of them (n = 14) had dual training in anaesthesia and critical care; 39% (n = 11) were trained in critical care as their primary medical specialty, whereas 7% (n = 2) were trained as anaesthesiologists, and one expert was an emergency medicine specialist. Most experts worked in the critical care department, 57% (n = 16), followed by cardiac anaesthesia, 25% (n = 7). 79% (n = 22) of the experts worked in university hospitals.

Experts survey – barriers

According to the experts, the greatest barrier to the implementation of CCE in their department is the lack of allocated time 60% (n = 17). Other factors included lack of experience/skill, 25% (n = 8), lack of formal qualification, 21% (n = 6), and lack of encouragement from colleagues, 18% (n = 5). Minor problems included no mentors 10% (n = 3), limited access to ultrasound 7% (n = 2), and legal consequences 4% (n = 1).

DISCUSSION

CCE is an essential component of intensive care practice. The ESICM recognised the need to include CCE as an essential competency for European Intensive Care Medicine training [4]. In 2022 Competency Based Training in Intensive Care (CoBa-TrICe) was updated and proposed the minimum standard of knowledge, skills and attitudes required for a doctor to be identified as a specialist in intensive care medicine in Europe [12]. However, it could be argued that these, and similar documents from other professional societies, have changed very little from the original documents published in 2011.

Barriers

Although ultrasonography is a recognised component of the assessment of critically ill patients [4, 13–16], its adoption is still limited by several barriers. The biggest barrier identified by our survey preventing the widespread use of CCE is the lack of appropriate training [17–21], resulting in insufficient experience/skill of the clinical team to confidently perform and interpret the examination, despite most respondents feeling confident in acquiring basic CCE windows. Both experts and regular respondents agree that lack of experience/skill is a major issue limiting the implementation of bedside echocardiography Crucially, a 2017 survey by Galarza et al. [21] showed that only five European countries had a national-accreditation programme, with supporting training structure, in this skill. Interestingly, access to ultrasound machines has become less of a barrier (19% of the respondents and 2% of experts), reflecting their increasing availability.

Another barrier highlighted in our survey was the lack of allocated time to perform bedside echocardiography; 43% of respondents did not have enough time to perform scans. In the expert survey, the issue was even more emphasised, with 60% of experts selecting lack of time as a main barrier. It could be argued that lack of time to train/teach ultrasound reflects the perceived lack of importance in clinical practice. Ultimately, the fact is that it is not mandatory in most European intensive care medicine training programmes. Clearly, this is contradictory to the various guidelines published. A reason for this contradiction is that the logistical challenges of operationalizing the inclusion of POCUS in the training programme are significant and it would not be appropriate to mandate training whilst access to training opportunities is lacking and/or inconsistent.

As a statement of intent, perhaps if the competencies are mandatory, resources, including time, would be appropriately provided to both trainers and trainees.

Reinventing the training paradigm

Conventional thinking states that the professional societies that publish the competencies will then run courses to disseminate the learning and train colleagues. Given their practical nature, these centralised courses will inevitably include a hands-on/face-to-face component. Centralizing training offers the benefits of providing consistent ultrasound training and overcomes the issue of lack of local trainers. It is ‘hoped’ that those who complete their training will become the next generation of trainers to propagate the learning. However, this is not the stated explicit aim. Only a small proportion of those who start their accreditation journey ultimately finish [6].

Furthermore, following attendance at such courses, it is expected that those who complete them will continue to train and learn under the supervision of local experts. It could be argued that, given the current state of POCUS (especially in Europe), this method has not been efficient. Such centralised pathways do not address the key issue of lack of local experts/trainers. As far as we are aware, none of the societies run an explicit ‘Train the Trainers’ course.

Furthermore, in our survey, only 8% (n = 119) of the respondents selected the accreditation process as the pathway they chose to learn CCE. Most choose to learn from departmental colleagues (26%) and online resources (24%). These local solutions are certainly the preferred option.

After a decade of competencies being defined by societies, perhaps it is time for a bottom-up approach rather than top down. We propose that the role of societies is not to provide centralised courses but rather to enable the running of more local courses (Table 2).

TABLE 2

Advantages and disadvantages of centralised vs. local courses

One of the solutions to provide bedside echocardiography core competencies in a standardised fashion is by obtaining accreditation through recognised national and international organizations. Nevertheless, local training authorities need to acknowledge ultrasound education as one of the essential components of residency training programmes and allocate appropriate time to facilitate teaching. However, there are limitations to our survey. Because our survey was distributed via an ESICM mailing list and social media, a selection bias is to be expected. The study’s generalizability might be restricted, as 50.8% (n = 327) of the responses originated from just three countries and 66% (n = 414) selected a university hospital as their primary institution. Because of this limitation, the findings from our study might not be applicable to or representative of a broader population. In our cohort, 80% (n = 511) of respondents reported having basic experience in CCE. This exceptionally high proportion of echocardiography users is most likely due to positive selection bias as physicians with interest in ultrasound were more likely to complete our survey. However, we must clarify that our survey was not specifically designed to assess CCE competency levels. Instead, our primary focus was on investigating the limitations and barriers associated with CCE utilization.

CONCLUSIONS

Teaching CCE despite wide recognition by international organizations still lacks a formal structure at the departmental level. Our survey identified four main barriers to implementation of bedside echocardiography: lack of appropriate training, lack of formal qualifications, issues to identify a mentor, and problems with dedicated time for the ultrasound.