Introduction

Over the last few decades, there has been a great expansion in the use of Patient Reported Outcomes (PROs) as an indicator of subjective experience in asthma and allergic rhinitis (AR), mainly for research purposes [1, 2].

PROs are defined by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else” [3]. Collecting PROs enhances the range of patient outcomes that can be evaluated beyond the traditional clinical and biological measures.

In the field of respiratory allergy, among PROs, great attention has been dedicated to Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL), a broad and multidimensional construct that refers to the impact of an illness and its treatment on a patient, as perceived by the patients themselves [4]. This is evident by the large number of specific questionnaires being validated [5, 6], and increasing assessment of this outcome when comparing groups of individuals in clinical trials and population studies.

The available data indicate that AR and asthma markedly affect the physical, emotional and social dimensions of patients’ experience [7, 8]. This is supported by evidence that successful treatment of respiratory allergy improves the HRQoL [9–13].

The implementation of PROs in clinical practice has recently been encouraged because of their potential to empower patients to self-manage their care [14], to support communication and partnership between physicians and patients, to affect care and outcomes, to improve patient satisfaction [15].

Unlike in other chronic conditions [16–18], the use of PROs in routine medical care with patients with respiratory allergy remains limited. This depends mainly on the lack of questionnaires with the necessary psychometric properties [19, 20] and practical characteristics [21] to support individual application.

The RhinAsthma Patient Perspective (RAPP) [22] has been developed and validated for the individual assessment of HRQoL keeping in mind the close relationship between asthma and comorbid AR [23–25]. It takes into account both upper and respiratory tracts allowing the capture of patients’ experience in clinical practice.

The RAPP satisfies all the psychometric requirements that are requested for use in a routine setting [26]. Moreover, it is a highly practicable and user-friendly tool. The simple scoring system and the availability of a cut-off point with high sensitivity and specificity in discriminating the achievement of an optimal HRQoL, ensure that immediate feedback is available. This allows clinicians to integrate HRQoL results into their daily practice.

The RAPP has been validated in Italy [22] and is now available also in Portuguese [27]. To date, it has been the only available tool that can be used in clinical settings to monitor HRQoL of patients with respiratory allergy.

Aim

The aim of this study was therefore to cross-culturally adapt the Polish version of RAPP on the basis of proposed guidelines [28] and to test its psychometric properties. This project formed part of a larger international study whose purpose was to test the psychometric properties of the RAPP in five languages (Spanish, French, Portuguese, Polish and English) and to make comparison about HRQoL in the involved countries.

Material and methods

Cross-cultural adaptation of the original RAPP into Polish

The original Italian version of the RAPP was translated into Polish by two independent Polish native speakers fully competent in both languages. They were asked that the translation of each item should be semantic rather than literal, to reach conceptual and linguistic equivalence. Backward translation was performed by two native Italian speakers with fluent Polish and blind to the original Italian version of the RAPP. A consensus meeting of all researchers including translators was held to assess the semantic and conceptual aspects and to resolve any discrepancies, ambiguities and problems.

Validation of the Polish version of the RAPP

Patients who visited the allergy outpatient clinic of the Barlicki University Hospital, Medical University of Lodz (Poland), between March 2017 and October 2018 were invited to participate in the study.

The Ethics Committee of the University of Genoa approved the study protocol (approval no. P.R. 333REG2016), that was also ratified by a local ethics committee. The protocol complies with the general principles of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki as amended in Edinburgh in 2000. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and informed consent was obtained from all patients before study entry.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: age > 18 years, literate native Polish speakers and having been diagnosed with asthma and AR according to GINA [29] and ARIA [30] guidelines.

Participants were excluded in case of the presence of other respiratory or ear–nose–throat disorders.

Each patient included in the study was examined at two different visits.

During the first visit the physician collected socio-demographic and anthropometric data, information about disease patterns, spirometry values, smoking habits, and current treatment. Patients were asked to fill in the Polish version of the RAPP along with three other PRO measures:

Short Form Survey (SF-12) [31], a validated tool for the assessment of health status. It is composed of 12 items providing two domain scores: a physical component score (PCS) and a mental component score (MCS), with sum score ranges from 0 (the worst possible health) to 100 (the best possible health).

Asthma Control Test (ACT), a validated questionnaire, widely used to assess the level of asthma control within the 4 weeks preceding the evaluation [32]. The tool consists of five questions that evaluate limitations in daily activities, amount of dyspnoea, the presence of nocturnal symptoms, the use of rescue medication and perceived asthma control. Patients assign a score from 1 (poorest control) to 5 (total control). The resulting ACT score is interpreted as follows: fully controlled asthma (score ≥ 25), poorly to partially controlled asthma (score 20–24), or uncontrolled asthma (score < 20) [10].

Symptomatologic Visual Analog Scale (VAS) [33]: a 100-mm long horizontal line in which patients indicate the global discomfort due to their AR during the previous week from 0 (not at all bothersome) to 100 (intolerably bothersome) (100 mm). The Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters proposed this simple measure to assess the AR symptom severity [22].

On the second visit, 4 weeks later, the Polish RAPP, the SF-12, ACT and Vas were collected. In order to assess any change in health status, patients were also asked to fill in a Global Rating Scale.

Between the visits all patients received treatment according to the current GINA and ARIA guideline recommendations.

The psychometric properties of the Polish version of RAPP were evaluated by means of consistency, reliability and validity statistical analysis.

The internal consistency of RAPP items was tested using Cronbach’sα coefficient, considering values greater than 0.70 acceptable [34], whereas higher scores are recommended for use in an individual patient [35]. Moreover, a sub-sample of patients with a stable health status (GRS = 0) was selected to perform inter-class coefficient (ICC) and Lin’s concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) in order to study scale reliability. For these coefficients a rule of thumb of 0.70 for group comparisons, and of 0.90 for comparisons within individuals is recommended [36].

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis [37, 38] models were estimated to test scale dimensionality. To assess the confirmative model fit, three indexes were considered: the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), the standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) and the comparative fit index (CFI).

Values from 0.4 to 0.8 of the Pearson’s correlation between the RAPP and SF-12 scores was intended as a test of convergent validity, while the group comparison of patients (ANOVA) derived from ACT, GINA and ARIA classification of severity served to test scale discriminant validity.

Scale responsiveness was evaluated by analysing the correlation between changes in RAPP scores and changes in GRS, VAS and ACT by means of Pearson’s correlation coefficients.

Finally, the minimal important difference, MID [39], was determined using the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve, with the adoption of the entire cohort for one dichotomization point (i.e., ‘no change’ vs. ‘any improvement or deterioration’).

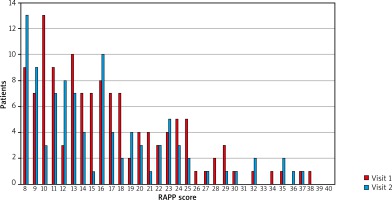

In addition, the possible effect of the education and smoking habits on patients’ answers was controlled using ANOVA, age effect was explored through correlation analysis, and to verify that RAPP properly represented patients’ quality of life levels the frequency distribution of scores was inspected.

Results

The study involved 127 patients, slight female majority (53.5%) with a mean age of 34.8 years (range: 18–66 years). The majority of patients had an academic degree (48%) or high school diploma (39.4%), while the remaining participants had a secondary school (9.4%) and primary school (3.2%) diploma. In terms of occupation, 74.8% were employees, 18.2% students, 3.9% unemployed and 3.1% retired. The prevalence of persistent asthma in the sample was 62.2%. ACT scores at the first visit indicated that 12.5% were totally controlled, 57.5% were well controlled, and the remaining 30% were uncontrolled. The mean value of AR and asthma quality of life was 16.6 at first visit and 16.1 at second visit.

The RAPP score distribution at the first and second visits is presented in Figure 1.

Cronbach’s α values equal to 0.85 at the first visit and 0.89 at the second one, indicate an appreciable internal consistency. Reliability, assessed in 43 patients reporting stable health status (GRS = 0), provides an ICC of 0.89 and a CCC value equal to 0.94.

The RAPP scale revealed a unidimensional structure that absorbed 43.6% of the total observed variance, and 1 residual greater than |0.10| at the first visit. Data from the second visit remained stable, with 51% of the total variance explained, and 4 residuals greater than |0.10|. The same structure was obtained from confirmatory factor analysis: the model fit indexes were all satisfactory, both at first (RMSEA 0.08, SRMR 0.04, CFI 0.94) and second visits (RMSEA 0.05, SRMR 0.04, CFI 0.98).

Convergent validity was achieved: correlations between RAPP scores and the Physical Component Score of SF-12 were significant at both first (r = –0.49, p ≤ 0.001) and second visit (r = –0.28, p < 0.001). Significant correlations were also found considering RAPP and the Mental Component Score of SF-12 (Visit 1: r = –0.28, p < 0.02; Visit 2: r = –0.27, p < 0.01). RAPP results, presented in Table 1, showed that the tool was able to discriminate between patients on the basis of the asthma control level and rhinitis severity (p < 0.03 for all the analyses). Moreover, RAPP was significantly associated with VAS (r = 0.47, p < 0.001) and ACT (r = –0.46, p < 0.001) in the sub-sample of 84 patients reporting an improvement or deterioration in health status.

Table 1

RAPP discriminant validity

A 1-point difference or change in RAPP (MID) maximizes sensitivity, specificity, and the number of individuals correctly classified (Table 2).

Table 2

The MID of RAPP obtained with the ROC analysis with different cut-off values

| Cut-off ≥ | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 0.754 | 0.529 |

| 4 | 0.755 | 0.411 |

| 3 | 0.765 | 0.313 |

| 2 | 0.876 | 0.247 |

| 1* | 0.893 | 0.189 |

RAPP scores showed no significant differences between smokers, former smokers, and non-smokers (ANOVA Fisher’s test: Visit 1: p = 0.25; Visit 2: p = 0.58), nor regarding age (Spearman’s correlation: Visit 1: r = –0.04; Visit 2, r = 0.06), nor level of education (ANOVA Fisher’s test. Visit 1: p = 0.26; Visit 2: p = 0.17).

Discussion

RAPP is the first tool for individual asthma and rhinitis HRQoL assessment in daily practice. In this study, RAPP was cross-culturally adapted from the original Italian version [22, 40] to Polish with two forward and backward translation and its psychometric properties was assessed in 149 patients with asthma and rhinitis. Our findings are in line with previous validation procedures in Italian and Portuguese populations. The Polish RAPP proved the unidimensional structure of the original Italian questionnaire, as previously confirmed in the Portuguese version. In terms of internal consistency, it has a satisfactory performance, with Cronbach’s α values that approach the recommended threshold for questionnaires to be used in clinical practice [35]. Test-retest reliability in patients reporting a stable health status was good (ICC = 0.89 and a CCC = 0.94). Construct validity was confirmed by the correlation with the physical and mental component of health status. RAPP showed discriminative ability with respect to asthma control and AR severity and it is responsive to changes in health. The ROC analysis indicates that 1 point is the smallest change that patients perceive as an improvement or deterioration. Our MID value is half of the value found in Braido and Todo-Bom [22, 27]. This is in line with the fact that the MID value is not a fixed value but it may vary in relation with the features of the population considered. This difference could be explained considering the different population of patients enrolled in the study.

Patient’s answers were not influenced by age, level of education or smoking habits, indicating that RAPP may be used in daily practice independently of patients’ characteristics and behaviour.

Conclusions

The RAPP was successfully cross-culturally adapted and validated for use with Polish speaking patients. Its psychometric properties were similar to those of the original Italian version and Portuguese version. The Polish version of RAPP can be recommended as a robust tool questionnaire to be used in clinical practice to monitor HRQoL of patients with asthma and AR.