Purpose

According to data from Polish National Cancer Registry, prostate and colorectal cancers are the first and the third most popular malignancies in male population. In 2015, the incidence of prostate tumor accounted for 17% and colorectal cancer for 15% of all cancers among male population [1]. Patient’s oncological awareness, screening programs, and increasing incidence rates of both above mentioned diseases lead to more frequent diagnosis of metachronous and/or synchronous prostate and rectal cancers. In 2015, in Lower Silesia Voivodeship, 9.1% of all cancers (1,204 cases) were diagnosed as multiple primary tumors, and 8.1% of them (98 cases) developed synchronously within 2 months. At that time, less than 10 cases of synchronous prostate and rectal cancer in our region were noted [2].

Patients with synchronous cancers usually report symptoms caused by rectal tumor and during additional exams, prostate cancer is unexpectedly diagnosed [3]. Due to the rarity of such cases, there are no standard treatment recommendations, and oncologists in multidisciplinary treatment teams (MTTs) need to provide an optimal curative management for two different cancers, with an acceptable risk of adverse effects to maintain the patient’s quality of life. Each of these cancers require different treatment approaches including surgery, chemotherapy, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), and radiotherapy with external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) or low-dose-rate (LDR)/high-dose-rate (HDR) brachytherapy (BT). This case report describes different option of radical one-step treatment of synchronously diagnosed prostate and rectal cancer with the use of preoperative radio-chemotherapy for rectal cancer and HDR brachytherapy boost for prostate cancer.

Material and methods

Data of a 61-years-old patient with good performance status, diagnosed in Lower Silesian Oncology Center in 2015 with synchronous prostate and rectal cancer, treated with HDR brachytherapy boost for prostate were collected. Both cancers were locally advanced and staged with AJCC 7th edition (2010) as rectal cT3N2M0 and prostate cT2cN0M0 adenocarcinomas, Gleason score 3 + 3 = 6, with maximum prostate specific antigen (PSA) level of 21.84 ng/ml (Table 1). Clinical staging was performed with pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), digital rectal examination, PSA serum level, colonoscopy, chest X-ray, and bone scan. Histological diagnosis was confirmed with trans-rectal prostate biopsy and endoscopic rectal biopsy. The NCCN, ESMO, GEC-ESTRO, ABS, and institutional guidelines were used to determine treatment strategy. MTT consisted of urologist, radiation oncologist, clinical oncologist, and oncological surgeon decided on synchronous radical treatment of both cancers. The patient was qualified for a long-term (3 years) ADT, chemoradiation, and surgery. Before starting the treatment, gold seed fiducials were implanted to prostate gland in order to perform image-guided radiation therapy (IGRT). For androgen deprivation therapy, a first-generation antiandrogen (flutamide) was administered for one month to prevent testosterone flare, followed by 2-3 years of LHRH analogue. External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) to a total dose of 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions was delivered with image-guided intensity modulated radiation therapy. Irradiated volume included prostate gland with the base (defined on MRI), rectal tumor with margin (defined on digital rectal examination, colonoscopy, computed tomography, and MRI), seminal vesicles, mesorectum, common iliac nodes below L5-S1 interspace, external and internal iliac nodes, and presacral and obturator nodes (Figure 1). According to our institution’s IGRT protocol, 7 mm margin around prostate contour was added, except for margin in rectum, which was 3-5 mm to create planning target volume (PTV). During the course of radiotherapy, clinical target volume was matched to prostate gland on cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) and then, the adjustment to gold fiducials was performed. The patient was requested to drink 500 ml of water, 30 minutes before radiation, as before CT planning. CBCT was performed on 1st, 2nd, and 3rd day of radiation, and then weekly to check the reproducibility of bladder filling. If not, the patient was asked to fill the bladder more. Long-course chemotherapy regimen based on 5-fluorouracil was administrated concurrently with radiation. Additional dose of 15 Gy in a single fraction was delivered within a week after EBRT to prostate volume with interstitial HDR brachytherapy (transrectal ultrasound-based 3D real-time planning for Iridium-192, MicroSelectron afterloader; Oncentra Prostate®, Nucletron, Veenendal, The Netherlands) (Figure 2). The brachytherapy boost was administrated in Greater Poland Cancer Center.

Table 1

Patient characteristic

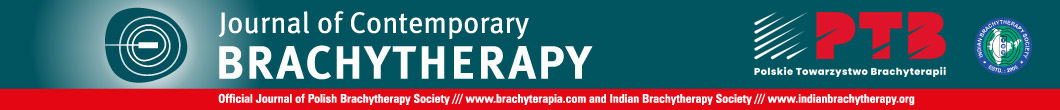

Fig. 1

Excerpt from the EBRT treatment plan. A) Cross section plane: red line – PTV, cyan – bladder, violet – prostate with seminal vesicles, pink – rectum with tumor; B) Sagittal section plane: red line – PTV, cyan – bladder, violet – prostate with seminal vesicles, pink – rectum; C) Cross section color wash plane 95% isodose covering PTV; D) Three-dimensional view of the irradiated volume (PTV – red color)

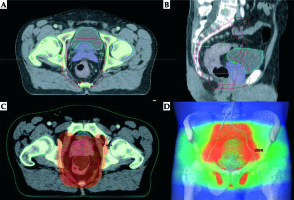

Fig. 2

Excerpt from the HDR brachytherapy treatment plan. A) Cross section reference plane: red line – prostate contour, yellow – urethra, blue – rectum, red dots – source positions; B) Cross section isodose color wash representing their relations to prostate, urethra, and rectum contours: blue – 90% isodose, light green – 100% isodose, yellow – 150% isodose, orange – 200% isodose; C, D) Three-dimensional right-oblique and coronal views of the volumes of interest along with the spatial source positions’ distribution inside the prostate volume

Planned target dosimetry constraints for EBRT were verified according to the QUANTEC guidelines [4], and for prostate brachytherapy according the GEC-ESTRO, ABS and institutional guidelines (prostate D90 > 90%, V200 < 15%, Dmax lowest achievable; urethra D10 < 125%, Dmax < 160%; rectum D10 < 75%, Dmax < 100% of prescribed dose; bladder constraints: not reported at time of treatment; Table 2) [5,6]. Acute and late gastrointestinal and genitourinary toxicities were evaluated with the National Cancer Institute common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE), version 4.0. Follow-up included physical examination, digital rectal examination, MRI, CT, colonoscopy, PSA, and carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA) concentration, according to guidelines [7].

Table 2

Brachytherapy treatment details

Results

Treatment tolerance of preoperative radiochemotherapy was good until the 20th fraction of radiation. The patient reported only nocturia 2-3 times by night. After the 20th radiotherapy fraction, the patient developed acute diarrhea with dehydration and hypokalemia. For 5 consecutive days, radiochemotherapy was paused. Following the break, the patient received total originally planned dose of radiotherapy. No supplemental EBRT fractions were added because of planned additional brachytherapy boost and surgery. There were no other acute genitourinary (GU) and gastrointestinal (GI) toxicities reported. Within a week, HDR-BT boost was administered (Table 2). Eight weeks after the completion of EBRT, the patient underwent sphincter-sparing, anterior resection (AR), and total mesorectal excision (TME) with end-to-end rectosigmoid anastomosis. The tolerance of surgery was good, with no toxicities reported.

Twenty-five months after the completion of surgery, GU or GI toxicities were not observed, and PSA level was 0.059 ng/ml. At that time of follow-up, post-treatment CT scans showed no evidence of recurrence. Currently, the patient is 45 months after the surgery. Hormonal treatment was terminated after 36 months and actual PSA level is < 0.003 ng/ml, with no GU or GI toxicities reported. Physical examination as well as imaging revealed no symptoms of local recurrence or distant metastases. Up till date, no signs of disease recurrence were reported by patient, nor revealed by physical examination. Performed imaging showed complete response, with no local recurrence or distant metastases.

Discussion

Since synchronous prostate and rectal cancers are rare cases, there is a lack of publications about one-step radical treatment approach for this kind of patients. All available papers are case reports or case series [3,8,9,10,11,12].

Lin et al. reported tree cases of Chinese men with synchronous prostate and rectal cancer safely treated with surgery including lower anterior resection (LAR) or abdominoperineal resection (APR) with radical retropubic prostatectomy (RRP) performed in a single operation [12]. Seretis et al. [3] in their review of literature presented the largest group of patients (n = 23) with synchronous prostate and rectal cancer. Most of patients (n = 8) were treated only surgically: prostatectomy with APR or LAR, depending on rectal tumor location. Only two patients received preoperative radiation therapy with APR, but rectal cancer staging was not assessed; therefore, it cannot be determined whether this was a correct approach. Only one patient in stage III (cT3N1) rectal cancer was treated according to current guidelines with preoperative radiochemotherapy. In this case, prostate cancer was treated with radiotherapy, with an additional dose to total 70 Gy prescribed to prostate field. There were no post-operative complications reported and during 14 months follow-up, patient was asymptomatic, with PSA level of 0.3 ng/ml [8]. Lavan et al. [10] analyzed 10 cases with synchronous prostate and rectal cancer, simultaneously treated for both tumors in 3 centers, using so called “shrinking field radiotherapy” including EBRT (45-50.4 Gy) for pelvic area and an additional dose to prostate (up to total dose of 70.0-79.2 Gy) with concurrent 5-FU chemotherapy. Nine of ten patients underwent surgery: anterior resection (AR) or APR, and one patient declined the surgery. Follow-up was assessed from initial diagnosis for median 2.2 years (range, 1.2-6.3 years). Five of nine patients had no evidence of disease during follow-up, other four were living with a metastatic disease. Two patients reported with significant late toxicity: first grade 3 GU toxicity (proctitis) and second grade 3 GI toxicity (anastomotic stricture). Qiu et al. [11] presented case series of 4 patients with synchronous cT3N1 rectal and cT1c prostate cancer, treated with chemoradiation, prostate brachytherapy boost, and surgery, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy. Initial dose of 45 Gy/1.8 Gy per fraction delivered with 3D EBRT encompassed the prostate gland, whole seminal vesicles, rectal tumor, internal iliac, external iliac, presacral, and perirectal lymph nodes. Three patients received additional dose to 54 Gy/1.8 Gy to the rectal gross tumor volume and sacral hollow, plus 1 cm planning target volume expansion with IMRT. Within 23-41 days after EBRT, all patients received additional dose of Cesium-131 (131Cs)-based LDR prostate brachytherapy to a prescribed target dose of 80-90 Gy, with dosimetry constrains for prostate V100 ≥ 90%, urethra D30 < 150%, and rectal V100 < 0.5 cc. After 2-4 weeks, patients underwent LAR with diverting loop ileostomy and 4-6 weeks later, adjuvant chemotherapy was applied. One patient from high-risk group prostate cancer received androgen deprivation therapy. Six to eight months after surgery, patients’ ileostomies were reversed. According to CTCAE criteria, first patient was observed with grade 1 GU, second with grade 1 GI toxicity, third with grade 2 GU and GI, and fourth patient was noted with grade 3 GI toxicity.

To the best of our knowledge, the current case report is the first of its kind to describe the utilization of HDR brachytherapy boost in the radical treatment of synchronous prostate and rectal cancers. According to the NCCN risk categories, our patient was in high-risk group, because of elevated PSA level and expected survival of more than 5 years. In this case, the patient should receive radical prostatectomy (RP) with nodal dissection or EBRT ± brachytherapy boost with long-term ADT (2-3 years) [13].

In terms of rectal cancer, the patient was qualified into bad-risk group, for which, according to the ESMO guidelines, 2013, treatment options included preoperative “short” course of RT or chemoradiotherapy (CRT), followed by total mesorectal excision (TME) [14].

The way our patient was treated connected two radical methods of treatment presented above. The patient was qualified for a long-term ADT, preoperative chemoradiation, in which PTV contained both prostate and rectum areas with appropriate nodal regions, and additional dose to prostate region delivered with HDR brachytherapy boost; after completion of that treatment, TME was performed.

This approach generated few problems with external beam radiotherapy planning such as an extent of irradiated area, a proper choice of sufficient dose and the best method of radiation delivery, minimizing the toxicity and maintaining or improving patient’s quality of life.

During preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer, the CTV encompasses tumor with appropriate margin, and peri-rectal, pre-sacral, and internal iliac nodal regions [15,16,17]. High-risk prostate cancer treatment with radiation therapy requires not only prostate gland with seminal vesicles volume irradiation, but also an addition of regional lymph node area, which involves common and internal iliac, pre-sacral and obturator nodal regions [18,19]. Irradiated volumes for these two types of cancers are in square or in close proximity with each other. Because of this, there is a technical opportunity to irradiate two CTVs for separate cancers in one volume.

In terms of radiation therapy in rectal cancer during treatment planning for our patient, there were two main preoperative dose schedules with 25 Gy/5 Gy per fraction without chemotherapy, or 50.4 Gy/1.8 Gy per fraction with chemotherapy, for more advanced tumors [14]. Regarding an elective nodal irradiation for prostate cancer, a dose of 50.4 Gy/1.8 Gy per fraction is high enough. Ablative doses in radical prostate cancer treatment are higher, because of low α/β ratio (approximately 1.5) of prostate adenocarcinomas [20]. In conventionally fractionated radiotherapy doses up to 76-80 Gy/2 Gy per fraction, which corresponds to biologically equivalent dose (BED1.5) of 180-200 Gy, improve disease control [21]. Higher dose to prostate volume may be delivered with few techniques including EBRT with “shrinking field technique”, standard fractionation or hypofractionation, and brachytherapy boost LDR or HDR.

As a standard of care, there are few rationales for using brachytherapy boost among patients with intermediate- and high-risk prostate cancer. HDR-BT boosts plans to the prostate are more conformal in comparison to IMRT plans [22]. BT, especially HDR when used as the only treatment modality, can spare dose to normal tissues, as compared to other techniques like volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT), scanned proton therapy (intensity-modulated proton therapy – IMPT), and scanned carbon-ion therapy (intensity-modulated carbonion therapy) [23].

LDR brachytherapy boost in comparison to dose escalated EBRT (DE-EBRT) (up to 78 Gy) for intermediate- and high-risk prostate cancer in ASCENDE-RT randomized trial revealed an improvement in bPFS, with no significant overall survival difference [24]. Additionally, median 6.5 years follow-up in this trial showed higher incidence of acute and late GU morbidities after LDR prostate brachytherapy boost, and non-significant tendency for worse GI morbidity [25].

Retrospective analysis using data from the National Cancer Database revealed statistically significant improvement in overall survival, when using LDR-BT boost among patients with unfavorable prostate cancer [26].

Similarly, there is meta-analysis comparing EBRT vs. BT boost for intermediate- and high-risk prostate cancer, suggesting BT boost as level I and grade A treatment recommendation (b-PFS improvement, with no difference at 5 years in overall survival). In terms of grade ≥ 3 late toxicity, meta-analysis suggested further investigations [27].

At Poland, there is a problem with LDR permanent seeds brachytherapy treatment reimbursement, and the access to this kind of treatment is limited. HDR brachytherapy is refunded, more popular, and widely accessible. The question is whether we can use HDR instead of LDR-BT boost with similar efficacy and equal or fewer adverse effects level? In phase 2 randomized pilot study comparing first 12 months of HDR and LDR brachytherapy as monotherapy, HDR-BT had lower urinary toxicity profile and higher QoL level [28].

The National Cancer Database analysis revealed HDR brachytherapy boost for prostate cancer as a good alternative for LDR boost in terms of improving overall survival [29]. Toxicity profile also seems to be acceptable, even if hypofractionated EBRT (37.5 Gy/15 fractions) with one HDR-BRT boost fraction (15 Gy/1 fraction) is prescribed (grade 3 or higher late toxicity rate of < 5%) [30].

However, there is a large SEER-based study, which reported non-statistically significant increase in grade 3 GU toxicity among patients treated with combination of EBRT with BT boost, both LDR and HDR (greater with HDR) [31]. In addition, we need to wait for results from currently ongoing BrachyQoL randomized controlled trial (NCT01936883), which directly compares short- and long-term toxicity profiles between LDR and HDR-BT boost approaches [32].

Our case report on HDR-BT boost proved to have safe toxicity profile, even when treating synchronous prostate and rectal cancer with additional chemotherapy and surgery.

Conclusions

Despite synchronous diagnosis of two different cancers, coordinated work of multidisciplinary treatment team helped to find radical treatment modality for both the diseases. Combination of androgen deprivation therapy, chemo-radiotherapy, brachytherapy, and surgery proved to be feasible and safe with good oncological outcome (over 45 months of local, regional, and biochemical control).

HDR brachytherapy as a boost seems to be well-tolerated and effective option for delivering proper treatment dose to prostate in case of simultaneous treatment of rectal and prostate cancer. Undoubtedly, further observations with greater number of patients is needed, where HDR brachytherapy boost toxicity profile treatment is thoroughly investigated.