A medication error can be defined as an event that can lead to patient harm while the drug is partly under the control of the health care professional. Most of the time, this is preventable. Medication error can result either from incorrect dosage (which is the most commonly reported type) [1], wrong dilution [2], wrong drug, wrong administration technique or/route [1], wrong time, faulty preparation, wrong patient, expired product, or mislabelling [3, 4]. Medication error is the third most common cause of inpatient mortality after respiratory and cardiovascular causes [1]. There is an estimated one medication error in every 133 anaesthetic procedures [3]. These figures underestimate the real problem because under-reporting is prevalent in all healthcare systems. However, it remains one of the preventable iatrogenic causes of patient harm.

Paediatric anaesthesia is prone to more such errors than in adults. This might be due to varying age groups, weights, doses, drug formulations, serial dilutions of drugs to reach the appropriate quantity for weight, and changes in pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics in paediatric patients due to the immaturity of their organ systems. The anaesthesiologist is responsible for drug prescription, preparation, and administration.

Medication errors could increase morbidity and mortality and healthcare costs [3, 5]. This also negatively impacts the general public’s confidence in healthcare professionals and health organisations. Additionally, it is associated with an additional burden for the healthcare professionals themselves, who must bear legal proceedings, shaken self- confidence, reputation at stake, and even in extreme cases manslaughter [3].

In this narrative review, we have tried to analyse the existing literature on the incidence and nature of medication errors and various available guidelines to reduce them and assess their effectiveness.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

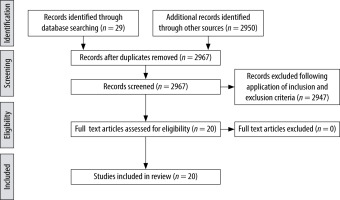

PubMed, Google Scholar, and Cochrane electronic databases were searched. The keywords searched were “medication error”, “drug error”, and “paediatric anaesthesia”. The study population for which we explored the literature were children less than 18 years of age and in the English language. A total of 2979 articles were retrieved on children and medication errors. NG and SG were the 2 authors who reviewed the articles independently. They identified the authors, year and country of publications, the study design, and the age and number of patients included in the studies. They also studied their primary outcomes (assess incidence, causes, and measures to minimise medication errors in children), the results, and conclusions of the various studies. A total of 21 relevant articles (Figure 1) were selected. It included 9 review articles, 6 observational studies, 3 quality control programs, 2 letters to the editor, and one editorial article (Table 1).

TABLE 1

Details of various articles on medication errors in chronological order

RESULTS

We have summarised all the essential details and made a detailed interpretation of the results (Table 1). We have attempted to identify significant and valuable interventions, summarising potential means to improve patient safety related to drug errors.

DISCUSSION

It is perceived that medication errors occur commonly, but the exact rate is uncertain. There are 2 review articles on the estimation of the incidence of medication error. Bratch et al. [6] tried to find the error rates based on 5 different method types. However, Feinstein et al. [7] found the meta-analytic estimate of the medication error rate across all studies to be 0.08%, or 1 out of 1250 anaesthetics. This is far too low for the expected value, which is consistent with the findings of Leahy et al. [8], who showed 105 medication errors among 287,908 cases. It suggests improper error reporting and a need for a more effective methodology to collect data. We have included 2 letters to the editor, highlighting the same problem of underreporting the actual number of events [9, 10]. The problem, therefore, is far more extensive than these data would indicate.

Drug errors are reported to be more common during drug administration (53%), compared with those due to prescription (17%), preparation (17%), and transcription (11%) [3]. The maintenance phase of anaesthesia is the most common stage at which medication error occurs, which accounts for 42% of the total error. In terms of incidence, it is followed by the induction phase (28%) and the beginning of surgery (17%) [3]. A prospective incident monitoring study in 2017 reported the incidence of medication error to be about 2.6%, with the drugs most commonly involved being opioids and antibiotics. Wrong dosage was the most frequent type of error (67%) [4].

Usually, such errors do not occur for a single reason [5], but from a chain of seemingly minor events, which, when combined, can lead to significant patient harm. This can happen at multiple steps, from prescription, preparation/formulation (especially serial dilutions for paediatric dosages) [2], administration, lack of communication, incomplete knowledge, inexperience [3, 11] (or sometimes over-experience), environmental factors like a hectic schedule, too many patients in hand, or fatigue [4] as well as patient factors like deranged renal function. Another important cause of these errors is cultural barriers and management failure among staff, which sometimes leads to a need for proper adherence to protocols. More evidence is needed about the exact causes of these errors.

Some drugs are inherently more harmful, and their improper use due to lack of knowledge could lead to substantial harm. For example, the sole presence of an epidural route of drug administration can lead to serious errors because drugs meant to be injected epidurally are sometimes inadvertently injected via the intravenous route, and vice versa, leading to potentially catastrophic outcomes.

Seniority can lead to overconfidence in one’s capabilities and disregard for fundamental principles to improve patient safety, thus leading to errors. Therefore, accepting equal susceptibility to errors amongst senior medical staff is imperative. This is a pre-requisite before any preventive measures can be incorporated [9].

Many methods have been adopted in different hospitals to study medication errors. In 1978 Cooper introduced critical incident reporting in anaesthesia to improve safety [5]. A similar study in 1993, the Australian Incident Monitoring Study (AIMS), was based on a critical incident reporting system, prospectively, which concluded the incidence of medication error to be 7.2%, none of which were fatal [5]. However, the incident reporting system underreports the exact number of cases because the practitioners tend to recall only those that resulted in adverse drug reactions. Moreover, what constitutes an error remains subjective. In 2017, a survey was conducted amongst the anaesthetists who attended the Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (APAGBI) annual meeting [10]. Its purpose was to identify the incidence of drug error, reporting behaviours and potential improvement strategies. There was a considerable difference in reporting mistakes among the anaesthetists, which underestimated the actual incidence because there was reluctance amongst the anaesthetists to self-report. Another concern was that practitioners fail to recognise that there has been an error unless it results in actual patient harm. Many incidents are usually underreported due to the fear of being blamed or due to legal aspects. To reduce the underreporting of critical incidents, there should be a ‘no blame’ (‘no fault’) drug error reporting and review system [12]. Other methods like overt or disguised observation [13] and prospective drug charts by pharmacists can be applied for better monitoring of drug errors [14]. An initiative was undertaken by the Society of Paediatric Anaesthesia (SPA) under the name ‘Wake Up Safe’. They tried to describe and characterise the medication error. Most events occurred during administration, and an incorrect dose was the most common cause. Seniority and experience did not affect the error rate [12].

Bratch et al. [6] conducted an integrative review of the literature on the type of methods used to study drug errors during anaesthesia and tried to estimate the error rates. Thirty studies were included in this review, and 5 types were identified: retrospective recall, self-reporting, observational, large databases, and observing for drug calculation errors. Employing retrospective recall, 1 in 5 anaesthetists admitted having encountered a medication error over the course of their careers. In self-reports, the rate was 1 in 200 anaesthetic procedures. However, in observed practice, drug error was found in almost every anaesthetic. In large databases, drug error constituted ~10% of anaesthesia incidents reported. The wrong drug and the wrong dose were the most common errors among the 5 methods. These studies were too heterogeneous to be compared, and the exact frequency of errors was uncertain. Thus, standardising the error reporting protocols in hospitals would help achieve more consistent databases for better research.

Strategies to reduce medication errors should focus on all the possible causes of error, ranging from patient-dependent to those arising from faulty organisational systems. Because the anaesthesiologist is responsible for all steps, from diagnosing the problem to drug administration, they should be actively involved in recognising all the risk factors and developing measures and protocols to mitigate them. The anaesthesiologist should participate in improving the managerial and operational glitches in the system to reduce drug errors.

Specific recommendations as given in published literature are as follows [3, 8, 15–17]:

Information: Establishing good communication between the teams to have all the information regarding the preoperative assessment to postoperative care and management. Availability of weight-based drug dosing for paediatrics, information on drug allergies, side effects, and drug interactions should be present [18]. Regular staff training in the causes and prevention of medication errors and building computer-based programs with built-in paediatric pharmacological databases for drug prescriptions can be done.

Communication: Encouraging double-checking electronic prescriptions and 2-person electronic prescriptions, and minimising the use of abbreviations should be practised.

Standardised packaging and presentation: Ensuring standardised storage of drugs in the Operating Theatre, with proper labelling and colour coding, using prefilled, labelled syringes, and standardising protocols for drug preparation.

Environment: Staff to remain more concentrated during drug preparation and administration, utilising ‘sterile cockpits’ where moments of silence are supported by the surgical team while the drug is being handled [18], shorter working hour shifts, staff awareness and education, computerised infusion pumps with alarms correctly set for dosages according to weight.

Equipment: Use of standard syringe pumps with pre-fed drug information and weight-based dosage range. Use differently designed connectors for different routes to prevent tubing misconnection and administration of the wrong drug through the wrong route [20].

Calculation errors: Encourage the use of readily available tabular or electronic weight-based references for drug dosing [19].

Quality assurance and risk management: Proper documentation of all the events and critical incidents of all errors or those nearly missed, whether the patient was harmed or not. Require a proper system to analyse them and conduct regular audit sessions to learn from past mistakes and monitor progress [12, 15, 21].

Including error case studies during trainee orientation [24].

Zero tolerance initiative, where the head of anaes-thesiology meets with the practitioner who failed to comply with the above medication administration policy, to understand where the pitfall is. The goal is to create a transparent environment in which the practitioners are comfortable enough to report errors and take responsibility for their mistakes [15].

Martin et al. [24], at a freestanding Academic Children’s Hospital, undertook a five-year quality improvement project based on FMEA (failure mode effect analysis), which was initially used in the aviation industry. Every step involved in a procedure is deconstructed and carefully evaluated for possible errors that could lead to the failure of the intended procedure. FMEA was performed in the operative room by a multidisciplinary team. A bundle of 5 targeted countermeasures were identified, including the medication tray to prevent vial swap, the medication cart top template designed to standardise the organisation of medication syringes, and syringe labelling with proper colour coding, infusion double check, and medication practice guidelines posted in every operating room. It was observed that the median medication error rate decreased from 1.56 to 0.95 per 1000 anaesthetics after the intervention.

Kanija et al. [22] initiated a quality improvement project based on FMEA at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Centre following an increase in the dosing errors of acetaminophen in the paediatric population. This project also highlighted the importance of proper communication between anaesthesia providers, PACU nurses, and parents/families.

Kaufmann et al. [23] reviewed existing recommendations and current evidence on preventive strategies to enhance patient safety in paediatric anaesthesia and summarised the recommendations for reducing the rate of medication errors. Apart from the already accepted strategies, they highlighted the importance of specialist standards with expertise in paediatric anaesthesia to improve the competency needed for regular lectures and courses addressing awareness of drug safety to enhance vigilance and safety culture [24].

Bekes et al. [1] compiled data from studies done on medication errors, their frequency, type, and outcome among paediatric patients over the past 10 years (2009 to 2019) and highlighted some of the successful error-reduction strategies described in the literature. They found that standardised labelling and prefilled syringes are the most effective of all strategies, giving a 65% and 53% reduction in error, respectively. Other effective strategies are double verification (41%), using drug library/electronic-based references (35%), and quality improvement safety analysis (35%). These error-reduction strategies must be standardised and implemented nationwide.

CONCLUSIONS

Perioperative safety in paediatric anaesthesia has always been challenging, with drug errors being one of the major concerns. Preventive strategies like drug labelling, colour coding, accurate dose calculations, and 2-person checking should be implemented. Encouraging healthcare professionals to undertake self-reporting might help determine the exact cause of the errors and prevent such mistakes in the future, thereby improving patient safety.