Genetics of psoriasis

Psoriasis is a complex disease with the interaction between genes, immune system and environmental factors implicated in onset and progression of the disease. The genetic background of psoriasis is evident by the familial prevalence of the disease. A study done by Farber et al. in 1974 shows that psoriasis is more common in first- and second-degree relatives of psoriasis patients and the concordance risk of psoriasis in monozygotic twins is 2–3 times higher compared to dizygotic twins (20–73% vs. 12.30%) [1]. The absence of 100% concordance in monozygotic twins and not characterized inheritance pattern in families with multiple cases of the disease implies multifactorial background of the disease considering the interaction of many genes with environmental factors. The enormous development of molecular genotyping technologies, in particular genome-wide association studies (GWASs) with large case-control data sets typed, have revealed that psoriasis is strongly dependent on genomic variations and enabled the description of numerous genetic variants that are associated with the disease. This in turn was crucial in understanding the pathogenetic pathways and molecular mechanisms that lead to psoriatic plaques. Without these discoveries, it would not be possible to introduce new, highly specific, pathogenesis-based treatments for this chronic, debilitating disease. Understanding the genetic determinants of psoriasis and putting into practice genomics-based susceptibility testing hopefully will allow to achieve the goal of personalized therapy for the disease.

The history of genetic research of psoriasis

The history of genetic research on psoriasis dates back to the early 1970s, when Russell et al. and White et al. independently observed that tissue class I compatibility antigens B37 and B57 encoded by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) genes located on the sixth chromosome (6p21.33) may be genetic markers of psoriasis susceptibility [2, 3]. The results of the research conducted in subsequent years among ethnically and racially different populations showed that this relationship is secondary to correlation with the HLA-Cw6 antigen and is associated with the phenomenon of non-random allele coupling in haplotypes characteristic of the MHC region – linkage disequilibrium (i.e., co-inheritance). Most reports that appeared in the following years unanimously pointed to the HLA-Cw6 antigen as a genetic marker of susceptibility to psoriasis [4–6].

Linkage studies

The early studies that shed light on the genetics of psoriasis were based on linkage studies, a statistical approach that enables the localization of disease genes to well define chromosomal regions. This method, introduced in the 1990s, uses family studies with numerous cases of psoriasis and is based on the analysis of microsatellite markers (short tandem repeats – STR), consisting of repeated, short motifs of 1–6 pairs rules. It is assumed that people with familial psoriasis have an increased probability of having the same marker located in the vicinity of the psoriasis susceptibility locus, therefore the linkage analysis technique was useful in determining areas of high risk of developing psoriasis, so-called risk intervals, and in the subsequent identification phase, genes by mapping or sequencing. Nevertheless, the feedback results should be interpreted with some caution. The restrictions about some of the conducted linkage analyses relate to the small number of studied groups of sibling pairs, the lack of phenotypic homogeneity of psoriasis in patients covered by the analysis or the demographic differences of the analyzed populations. Despite these limitations, linkage analysis identified fifteen different regions (known as psoriasis susceptibility 1-15 – PSORS1-15) that were supposed to contribute to disease susceptibility [7] (Table 1). Of these, only PSORS1 was robustly validated in all examined cohorts. This led researchers to conclude that the interval harbored a major genetic determinant for the disease [8]. Weaker linkage signals at the PSORS2 and PSORS4 regions were observed in more than one dataset, suggesting that these were genuine susceptibility loci [9–13]. Linkage to the remaining PSORS regions could not be replicated in independent studies [7].

Table 1

Psoriasis susceptibility loci and candidate genes

PSORS1 – major susceptibility locus in psoriasis

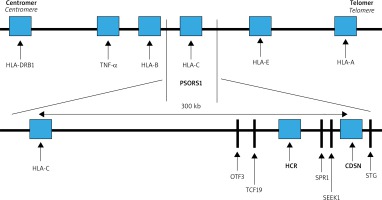

The strongest correlation with psoriasis maps to the PSORS1 locus. This region covers about 300 kb (thousands of base pairs) from the corneodesmosin (CDSN) gene to HLA-C within the MHC on chromosome 6 (Figure 1). The SNPs detected at least nine non-HLA-C genes located telomerically to HLA-C locus: HCR, CDSN, POU5F1, TCF19, HCG27, PSORS1C3, PSORS1C2 (SPR1), PSORS1C1 (SEEK1) and STG. Of these, three: HLA-C, CCHCR1 and CDSN were highly polymorphic and harbored coding variants that were significantly associated with psoriasis [8]. Ultimately, the results of extensive multicenter studies published by Nair et al. indicated HLA-Cw*06 as the main allele of psoriasis susceptibility in PSORS1, accounting for about 30-50% of the genetic involvement to the disease [8]. In most studies of the European populations, the HLA-Cw*06 allele occurs in 55–80% of patients with early onset psoriasis, while in a healthy population it usually does not exceed 20% increasing the risk of psoriasis 9 to 23-fold [14]. Moreover HLA-Cw*06 correlates with earlier onset, positive family history and more severe disease course. It has also been shown that in patients homozygous for the HLA-Cw*06 allele, the risk of developing psoriasis is 2.5 times higher compared to heterozygous ones [14]. HLA-Cw*06 positive individuals are more likely to have a guttate psoriasis preceded by an upper respiratory streptococcal infection.

Several hypotheses explain the relationship between HLA-C as an antigen presentation molecule and the molecular pathogenesis of psoriasis. HLA-C is a very likely candidate gene because it encodes MHC class I molecule contributing to the immunological response by participating in the presentation of short peptide non-self antigens to ab TCRs CD8+ T cells and in that way activating natural killer cells. Presuming the ability of HLA-C to present antigens and basing on the hypothesis that the lesional CD8+ T cells react against keratinocytes, it was assumed that HLA Cw*06 has a high ability to bind suggested psoriatic autoantigens: a specific melanocyte auto-antigen ADAMTSL5 (peptide from ADAMTS-like protein 5), a disintegrin and metalloprotease domain containing thrombospondin type 1 motif-like to CD8+ T cells, which activates IL-17 production by CD8 T and LL-37 (a 37 amino acid C-terminal cleavage product of the antimicrobial peptide, cathelicidin) produced by keratinocytes, activating both CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and CD4+ T helper cells in psoriasis [15–17]. LL37-specific T cells can be found in lesional skin or in the blood of patients with psoriasis, where they correlate with disease activity. Both autoantigens are recognized by T cells by being presented by HLA-Cw*06 [15–18].

The PSORS2 locus

PSORS2 region within 17q25.3 chromosome was identified on the basis of linkage studies in two ethnically different multigenerational families (Caucasian and Asian) with numerous cases of psoriasis [19]. This area includes the CARD family which encompasses scaffolding proteins that activate nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) that is highly expressed in keratinocytes. People with a gain-of-function mutation in the gene encoding the protein CARD14 (caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 14, also called CARMA2 or BIMP2) have been shown to have increased the risk of psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and familial pityriasis rubra pilaris. The NF-κB signaling pathway plays a role in stimulating the inflammatory production of interkeukin (IL) 17 and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) – pro-inflammatory cytokines [20]. What is more, GWAS research has uncovered common alleles in case-control studies, which shows that CARD14 contains both common variants with low-effect and rare but high-penetration mutations [21].

The PSORS4 locus

The PSORS4 region maps to chromosome 1q21, where it spans the Epidermal Differentiation Complex (EDC) with multiple genes responsible for epidermal development and maturation. EDC genes are activated in the final phases of keratinocyte differentiation and include, among others: loricrin, involucrin, filaggrin, late cornified envelope proteins (LCE) genes. Within the LCE region, three gene families are distinguished: LCE1, LCE2 and LCE3. De Cid et al. first demonstrated the association with psoriasis of the LCE complex containing a reduced number of copies of the LCE3C and LCE3B genes, while – what is worth emphasizing – the LCE3C/LCE3B deletion was not demonstrated in patients with atopic dermatitis [22–24]. This observation, together with the results of other reports indicates that there is no mutation in the filaggrin gene in psoriasis, which indicates that these two chronic inflammatory skin diseases are characterized by a different defect of the epidermal barrier.

Genetic variants in different psoriasis phenotypes

HLA-Cw*06 is currently considered as a genetic variant affecting the chronic plaque psoriasis phenotype. This allele is more common in patients with psoriasis beginning at a young age with a positive family history, in guttate psoriasis, in more severe forms of the disease [6, 14, 25]. In individuals with the guttate form, psoriasis is often initiated with preceding streptococcal sore throat that leads to believe that in HLA-Cw*06 risk allele individuals infectious pathogens are probably the initiating triggers. Recent studies have shed light on the genetic determinants of rare forms of psoriasis – a group of severe skin disorders, with systemic upset characterized by eruptions of neutrophil-filled pustules: pustulosis palmoplantaris (PPP) and generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP). Pustular eruption may be the only manifestation of the disease or may occur concurrently with chronic plaque psoriasis. Remarkable clinical and histopathological differences as well as a distinct response to therapy indicate that plaque and pustular psoriasis may be entities with different etiology. Palmoplantar pustulosis shows no relationship with any of the three candidate genes at PSORS1 locus (HLA-Cw*6, HCR*WWCC, and CDSN*5), and some authors suggest it to be a phenotypically (affects females in the perimenopausal period as well as cigarette smokers) and genetically distinct disorder [26, 27]. In terms of GPP in 2011, two groups of researchers independently described a mutation in the IL36RN gene [28, 29]. IL36RN belongs to the IL-1 cytokine family, involved in innate immunological response. IL36RN encodes for an interleukin 36 receptor antagonist molecule that inhibits IL-36 proinflammatory activity. The mutation of the IL-36 loss-of-function gene causes an uncontrolled increase in the proinflammatory IL-36 signaling pathway, with subsequent activation of IL-8, and IL-6. Biallelic mutations in IL36RN gene have been described in 21-41 % of the Caucasian and Asian patients with GPP [30]. Two additional genetic variants have been also described in GPP and PPP – CARD14 and APIS3 (encoding a subunit of the adaptor protein 1 complex), although latest studies by Mossner et al. suggest that AP1S3 and CARD14 variants have a much lower impact in GPP than variants in IL36RN [31]. Pustular psoriasis often coexists with chronic plaque psoriasis, therefore it is assumed that also in this common form of the disease, the disturbance of the IL-36 signaling pathway plays a role. Chronic plaque psoriasis has been shown to be correlated with over activation of IL-36 and IL-36 blockade has a significant anti-inflammatory activity. Thus, the hypothesis that the IL-36 signaling pathway may be a therapeutic target not only in pustular psoriasis, but also in chronic plaque psoriasis is justified [32–34].

Genome-wide association studies in psoriasis

At the beginning of the century, a huge progress in genotyping technologies was observed. It led to the introduction of GWAS, where large case-control datasets are typed at hundreds of thousands of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The success of GWAS resulted in developing target genotyping platforms, such as ImmunoChip referring to the SNPs previously associated with immune-mediated disorders and the Exome-wide chip enabling analyzing genetic markers within coding regions. Up till now, genome-wide association studies together with target genotyping platforms performed in different ethnic populations, have identified approximately 50 genetic susceptible markers associated with the risk of psoriasis at genome-wide significance p < 5 × 10– 8 [35–47]. The summary of non-MHC psoriasis genetic risk markers identified by GWAS at genome-wide significance p < 5 × 10–8 in European populations has been presented in Table 2 [48, 49].

Table 2

Non-MHC psoriasis genetic risk markers identified by GWAS in European populations at genome-wide significance p < 5 × 10–8 [48, 62]

The majority of psoriasis risk SNPs determined by GWAS technique is situated near the genes encoding molecules involved in adaptive immunity, innate immunity and skin barrier function. Up till now, the region involving MHC class I on chromosome 6p21 is the genetic locus associated with the greatest risk of psoriasis, and is called PSORS1. Among genes identified in the locus, HLA-C*06 presents the strongest association with the disease, that has been proved in different ethnic populations.

HLA-Cw6 encodes a major histocompatibility complex I (MHCI) allele critical for CD8+ T-cells priming and subsequent cytolytic targeting of cells [50–55].

Outside the MHC region, numerous SNPs within the endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1 (ERAP1) gene have been proven to have an effect on genetic predisposition to psoriasis [56]. ERAP1 encodes the protein involved in the process of N-terminal trimming of antigens allowing their presentation in the context of MHC class I that results in the activation of CD8+ lymphocytes. The association of ERAP1 with the risk of psoriasis has been also confirmed in the population of northern Poland in the rs26653 marker [57]. These results show the evidence of the primary role of the adaptive immune system in the pathogenesis of psoriasis.

Numerous SNPs associated with the risk of psoriasis identified by GWAS proved the role of the innate immune system in the pathogenesis of the disease. In general, these can be divided into genetic markers involved in: effector T-cell function and differentiation (ETS1, RUNX3, TNFRSF9, MBD2, IRF4), type I interferon and cytokine signaling (ELMO1, TYK2, SOCS1, IFIH1/MDA5, RNF114, IRF4, RIG1/DDX58, IFNLR1/IL28RA, IFNGR2), and regulation of NF-κB associated inflammatory signaling pathways (TNFAIP3, TNIP1, TYK2, REL, NFkBIA, CARD14, CARM1, UBE2L3, FBXL19). To continue, the discovery of genetic factors implicated in psoriasis involved in IL-23/IL-17 axis (IL23R, IL12B, IL12RB, IL23A, IL23R, TYK2, STAT3, STAT5A/B, SOCS1, ETS1, TRAF3IP2, KLF4, IF3) provided many insights into interactions between innate and adaptive immune responses in the spectrum of immunological disturbances of the disease [58].

Independent groups of researchers showed the association of late cornified envelope genes involved in the skin barrier functioning with psoriasis. Numerous observations in both European and Chinese populations have proven a common 30-kb deletion in LCE3B and LCE3C genes (LCE3C_LCE3B-del) to predispose to psoriasis [21, 47, 59]. The loss of this fragment is considered to be responsible for the dysfunction of reparative mechanisms of the skin barrier after mechanic trauma [60].

Although the GWAS findings provided many insights into specific genetic predisposition, immunological mechanisms and skin barrier function that may play role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, they still explain less than one third of the disease genetic heritability in the European populations [21, 61]. This phenomenon is known as missing heritability [52]. In the context of complex disorders, it may be explained by existence of gene-gene, gene-environmental interactions or regulation of gene expression by epigenetic mechanisms [49, 62]. To continue, GWAS analyzes the independent effect of each SNP that can be insufficient to account for missing heritability. What is more, based on the GWAS results, the minority of known genetic psoriasis risk loci span a single gene, whereas the majority associates with multiple transcripts or non-coding regions. This results in limitations in explaining certain biological pathways as well as determination of specific cells mediating pathways involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Finally, within an increasing role of next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques as well as the development of new statistical methods it is likely that more genetic signals will be discovered.

Epigenetic changes in psoriasis

Epigenome is a set of chemical modifications of DNA and histone proteins which cause the changes to the chromatin structure and influence the activation of transcription process of certain genes, and then the process of translating new mRNA on the polypeptide chain. Epigenetic changes do not change the genetic code, i.e. DNA sequence, but rather the expression of certain genes.

Epigenetic processes can regulate the gene expression at three different levels:

The methylation or demethylation of cytosine in gene promoter sequences. Methylation/hydroxymethylation of a promoter causes the gene to become inactive and not susceptible to transcription. In contrast, demethylation of a promoter causes the gene to be susceptible to transcription so that the protein which the gene codes can be produced.

The modification of histones chemically (methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, sumoylation, ubiquitylation) which leads to changing the structure of cell nucleus chromatin. As a result, the density and availability for enzyme complexes taking part in the transcription process may change. Histone acetylation and H3 lysine 4 trimethylation are associated with active genes transcription and open chromatin structure, while trimethylation of H3K9 and H3K27 are associated with transcriptional repression and closed chromatin structure.

By the non-coding proteins of RNA particles: long non-coding RNAs (lnRNA), micro-RNAs (miRNAs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and Pivi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs). Recent studies have demonstrated that these RNAs are capable to regulate gene expression at the transcriptional, post transcriptional and epigenetic level. For example micro-RNAs which join specifically to the complementary mRNA particles, influence its stability and miRNA/mRNA complex cannot join the ribosome, in consequence is degraded in cytoplasm, which leads to inhibition of gene expression by blocking the process of translation [63–75].

Epigenetic changes in psoriasis

Epigenetic modifications are considered essential in the pathogenesis of psoriasis as they account for keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation, resulting in aberrant increases in epidermal thickness, abnormal keratinocytes inflammatory cells communication, neoangiogenesis and chronic inflammation [63–68].

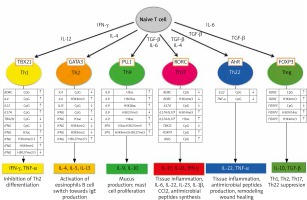

Epigenetic changes also play a fundamental role in the processes of differentiation of the CD 4 (+) T lymphocyte subpopulations that are so important for the pathogenesis of psoriasis [70]. Figure 2 illustrates epigenetic changes in the promoter regions of selected genes and in histones observed in the time of differentiation of CD4(+) T cell subpopulations.

Figure 2

Epigenetic modifications of DNA and histones in the development of different set of CD4 (+) T cells (from Potaczek et al. 2017 modified [70])

Histone modification in psoriasis

Zhang et al. are the first authors who have found that global histone H4 hypoacetylation was observed in PBMCs (peripheral monoclonal blood cells) from psoriasis vulgaris patients [72]. There was a negative correlation between the degree of histone H4 acetylation and disease activity in patients as measured by PASI. Global levels of histone H3 acetylation, H3K4/H3K27 lysine methylation did not significantly differ between psoriatic patients and controls. mRNA levels of P300, CBP and SIRT1 were significantly reduced in PBMCs from patients with psoriasis vulgaris compared with healthy controls, while mRNA expression levels of protein involved in histone modifications: histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1), histone-lysine N-methyltransferase (SUV39H1) and histone-lLysine N-methyltransferase EZH2 (enhancer of zeste homolog 2) were significantly increased in psoriatic patients, which allowed the authors to conclude that histone modifications are aberrant in the PBMCs of psoriasis vulgaris patients.

Ovejero-Benito et al. [71] studied epigenetic changes in responders and non-responders to biological drugs (ustekinumab, secukinumab, adalimumab, ixekizumab). Significant changes in methylated lysine 27 in histone 27 (H3K27) and methylated lysine in histone 3 (H3K4) in patients with psoriatic arthritis were found between responders and non-responders. Authors suggest that H3K27 and H3K4 methylation may contribute to patients’ response to biological treatment in psoriasis [71].

DNA methylation changes observed in psoriatic skin

The methylation of cytosine residues is the most frequently observed post-replication change in DNA. It is estimated that in mammals, 60–70% of cytosines are constantly methylated. Particularly rich in cytosine residues, referred to as CpG sites, are the promoter regions of genes, i.e. their regulatory sites that precede the initiation sites of transcription. Specific proteins, transcription factors that regulate the transcriptional process are added to the promoter regions. Methylation of cytosine in the gene promoter prevents the incorporation of transcription factors and transcriptases and, as a result, blocks the process of its expression. Demethylation activates the promoter and allows the gene transcription process to begin. DNA methylation occurs with the participation of specific DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) whereas DNA demethylation is catalyzed by tet methylcytosine dioxygenases 1-3 (TET – ten-eleven translocation gene protein) enzymes. Cells with a similar function show similar gene methylation patterns [63–67, 75–78].

Zhang et al. observed that the peripheral blood cells of psoriasis patients have an increased expression of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) as compared to healthy controls [77]. In the skin and epidermis, the hypermethylation of the promoter gene involved in cell cycle regulation, p16INK4a (cyclin-dependent kinase 4 inhibitor A) was observed and as a result, there has been a reduction in the following genes: P53, p14ARF, and ID4 (inhibitor of differentiation 4). The consequence of this is the inhibition of cellular differentiation and parakeratosis [77–81].

The pioneer study of global epigenetic of psoriasis was published in 2012. Authors analyzed the methylation status of more than 27,000 CpG sites in skin samples from lesional and non-lesional skin of patients with psoriasis and skin of healthy controls. 1,100 differentially methylated CpG sites were detected between psoriatic and control skin. Twelve CpG sites mapped to the epidermal differentiation complex (S100 Calcium Binding Proteins: S100A3, S100A5, S100A7, S100A12, sperm mitochondria associated cysteine rich protein – SMCP, small proline rich proteins: SPRR2A, SPRR2D, SPRR2E, late cornified envelope protein 3A – LCE3A). The most extreme change was found in cg16139316, which lies upstream from S100A9. There was a decrease in methylation at these sites, and they mapped close to genes that are highly upregulated in psoriasis. The investigators analyzed 50 of the top differentially methylated sites to separate/differentiate skin from patients with psoriasis from that of controls. Interestingly, with anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment, these methylation changes in patients reverted back to baseline [76].

Chandra et al. [75] used the genome-wide DNA methylation profiling and have found that differentially methylated genes in psoriatic skin regions were associated with psoriasis. Top differentially methylated genes overlapped with PSORS regions including S100A9, SELENBP1, CARD14, KAZN and PTPN22 showed an inverse correlation between methylation and gene expression. The authors made an interesting observation that in psoriatic skin with Munro microabscess, there is an increased expression of differentially methylated genes, responsible for the chemotaxis of neutrophils forming abscesses [75].

Non-coding RNA and their role in psoriasis

Genome-wide association studies have identified many psoriasis-associated genetic loci in the Caucasian population [82, 83]. However, most genome-wide association study signals lie within non-coding regions of the human genome [63–66, 84, 85]. The thesis is well documented today that non-protein coding DNA regions plays the role in genetic and epigenetic of many diseases and included account “missing heritability”.

Two main classes of non-coding RNA, plays the role in pathogenesis of psoriasis: long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) and micro RNA (miRNAs) [64–66, 68, 85–94].

Long non-coding RNA in psoriasis

Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), defined as non-protein coding RNA transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides, are acting as key regulators of diverse cellular processes. Three different groups of lncRNA can be categorized, namely, natural antisense transcripts (NATS), intronic RNA (IncRNAs), and long intergenic (intervening) non-coding RNA (lincRNAs). lncRNA are involved in epigenetic silencing, splicing process regulation, translation control, regulating the apoptosis and cell cycle control. Moreover, the expression levels of various lncRNA are closely related to epidermal differentiation and immunoregulation [85–93]. There are many examples illustrating that lncRNAs are also involved in regulation of a variety of skin pathological conditions including skin cancer, wound healing and psoriasis [85–88].

Tsoi et al. analyzed the expression of lncRNA in involved and uninvolved psoriatic skin and detected 2942 previously annotated and 1080 novel lncRNAs, which were expected to be skin-specific. Their results indicated that many lncRNAs, in particular those that were differentially expressed, were co-expressed with genes involved in immune-related functions. Additionally, novel lncRNAs were enriched in the epidermal differentiation complex. They also identified distinct tissue-specific expression patterns and epigenetic profiles for novel lncRNAs. Altogether, these results indicate that great deals of lncRNAs are involved in the immune pathogenesis of psoriasis [87, 91].

Two important lncRNAs are involved in the control of epidermal differentiation: ANCR and TINCR. ANCR (Antidifferentiation non-coding RNA) acts as a negative regulator of epidermal differentiation. Loss of ANCR in progenitor cells rapidly induces the differentiation program; therefore, it is needed to suppress premature differentiation in the basal layer of the epidermis. In contrast, TINCR (terminal differentiation-induced non-coding RNA) is highly expressed in the differentiated epidermal layer and promotes keratinocyte differentiation [88].

A study of Sonkoly et al. indicated that long non-coding RNA – PRINS (psoriasis-associated RNA induced by stress), is elevated in non-lesional skin areas in patients with psoriasis while it is decreased in the psoriatic plaques. PRINS contributes to psoriasis via the downregulation of G1P3, a gene coding protein with anti-apoptotic effects in keratinocytes [89].

Recently, Qiao et al. [93] have suggested that the other cytoplasmic lncRNA – Msh homeobox 2 pseudogene 1 (MSX2P1) was upregulated in psoriatic lesions compared with normal healthy skin tissues, human immortalized keratinocyte cells and normal human epidermal keratinocyte cells. LncRNA MSX2P1 facilitated the progression and growth of IL-22-stimulated keratinocytes by serving as an endogenous sponge directly binding to miR-6731-5p and activating S100A7. Authors speculate that the biological network of MSX2P1-miR-6731-5p-S100A7 might be a potential novel therapeutic target for the future treatment of psoriasis [93].

The role of micro-RNAs in psoriasis

Micro-RNAs (miR) are small biological molecules that regulate the expression of over 30% of human genes at a post-transcriptional level. These are non-coding RNA molecules with a length of 22–25 base pairs, capable of negatively modulating gene expression by binding to the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs). The resulting complex undergoes degradation in the cytoplasm and, as a result, the translation process is blocked and the gene product is not produced in the cell. It is estimated that miRNA codes 1–3% of genes in the human genome [64–69].

The study of the miRNA expression profile was focused after evidence suggested that epigenetic mechanisms may have an influence on DNA outside of promoter and structural DNA genetic regions. About 60% of human mRNAs involved in the coding of cell proteins are regulated by miRNAs and more than 1800 miRNAs were identified, which indicates that miRNAs are capable of regulating almost all living processes. In this way, epigenetic factors can affect the transcriptional regulation of mRNAs involved in cell proliferation, migration, differentiation or inflammation [64–69, 93–95].

miRNAs play the role in the processes of apoptosis, cell proliferation, morphogenesis and differentiation of cells, metabolism regulation, and signal transduction in the cell. One type of miRNAs can block the functions of many different genes, also one gene can be blocked by different types of miRNAs. These molecules act in the interior of the cells in which they are produced, but they can also be secreted into body fluids such as plasma, tissue fluid, milk and urine. They are protected by the fragments of cell membranes (exosomes) or by combination with high-density lipoproteins from enzymatic degradation in the plasma. The miRNAs contained in exosomes secreted by the cell can be used in a cell-to-cell communication. They can penetrate into the interior of neighboring cells and modify the expression of genes in them. It has been shown that the miRNAs contained in milk may modulate the functions of the newborn’s immune system, favoring the formation of regulatory lymphocytes Treg [68, 69, 85, 93–95].

Most of the studies of miRNAs in association with psoriasis address the plaque-type variant and so far, more than 250 miRNAs are aberrantly expressed in psoriatic skin. Majority of miRNAs are upregulated in the psoriatic skin, only a small number of them are downregulated [69, 96–105].

Some miRNAs deregulated in psoriatic skin and their function are listed in Table 3 [106–138].

Table 3

Changes in the microRNA expression observed in psoriatic skin and peripheral blood cells

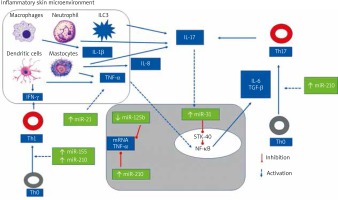

Through the regulation of their multiple target genes, miRNAs in psoriasis regulate the development of inflammatory cell subsets and have a significant impact on the magnitude of inflammatory responses. miRNAs can regulate differentiation, proliferation and cytokine response of keratinocytes, activation and survival of T cells and the crosstalk between immunocytes and keratinocytes through the regulation of chemokine and cytokine production [63–69, 93–96].

Figure 3 illustrates the role of selected miRNAs in the pathogenesis of psoriasis.

Figure 3

The role of selected mi-RNAs in regulation CD4(+) Th cells differentiation and cytokines synthesis

The most upregulated miRNAs in the psoriatic skin are skin-specific (miR)-203, hematopoietic-specific miRNAs: miR-142-3p and miR-223/223, angiogenic miRNAs: miR-21, miR-378, miR-100, miR-31, miR-21, miR-210, and proinflammatory miR-155 [64, 69, 93–101, 107].

miR-203 is a skin-specific miRNA, which is exclusively overexpressed in psoriatic keratinocytes and is involved in angiogenesis and keratinocyte differentiation. Their target genes are: SOCS-3, SOCS-6, p63, TNF-α, IL-8 and IL-24. SOCS3 (suppressor of cytokine signalling3) is a negative regulator of STAT3 pathways. Increased expression of miR203 leads to decreased SOCS3 levels in psoriatic skin, which may consequently result in sustained activation of the STAT3 signaling pathways. STAT3-activated transcription of EGFR, IL-6, TGF-β genes, blocks apoptosis, favors cell proliferation and survival and promote angiogenesis [69].

Additionally, in normal human keratinocytes, the increased miR-203 is reported to be induced by combinations of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1α, IL-17A, IL-6, and TNF-α, which coupled with a critical role of miR-203 in epithelial differentiation, suggesting that miR-203 is crucially implicated in the hyperproliferative phenotype of psoriatic lesions [69, 110, 111, 125, 138, 139].

miR-155 plays an important role in many processes including cell growth and proliferation. By decreasing the expression of IL-4, a cytokine that characterizes the T helper (Th)2 phenotype, miR-155 promotes expression of interferon γ (IFN-γ) and differentiation of Th0 cells towards a Th1 phenotype. Their target genes are SOCS1 (suppressor of cytokine signaling 1) and CTLA4 (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4). SOCS1 is a negative regulator of JAK/STAT and NFKB pathways playing the role in regulation of Treg and Th1 and Th17 differentiation, cytokines and TNF-α production. CTLA4 is the protein of Treg cells which inhibit T effectors cells. A study done by Xu et al. indicated that MiR-155 promotes keratinocyte proliferation and inhibits apoptosis by PTEN 11 signaling pathway in psoriasis [113]. In keratinocytes, miR-155 is induced by TNF-α and IFN-γ. As a proinflammatory miRNA, via positive feedback, miR-155 increases the production of TNF-α [69, 99, 104, 114, 119].

miR-210 induces Th17 and Th1 differentiation and inhibits Th2 differentiation through STAT6 and LYN repression [106]. FOXP3 playing the major role in Treg differentiation is a miR-210 target gene. miR-155 impairs the immunosuppressive functions of Tregs in CD4(+) from healthy controls, while inhibition of miR-210 reverses the immune dysfunction in T cells from psoriasis patients [115]. Overexpression of miR-210 leads to an increased proinflammatory cytokine (IFN-γ and IL-17) expression and decreased regulatory cytokine (IL-10 and TGF-β) expression in CD4+ T cells [115].

miR-31 enhances NF-κB signaling; modulates inflammatory cytokine and chemokine production in keratinocytes and regulates keratinocyte proliferation [102, 103]. The target of miR-31 is the gene of protein phosphatase 6 (ppp6c), acting as a negative regulator that restricts the G1 to S phase progression. The rise of miR31 directly inhibits ppp6c expression, thus enhancing keratinocyte proliferation. Moreover, miR-31 regulates the production of inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, IL-17 and IL-22) and stimulates leukocyte chemotaxis, thus inhibiting miR-31, which may be a potential therapeutic option in psoriasis [69, 102, 103, 105, 118, 119, 136].

miR-21 is overexpressed in psoriatic skin lesions, psoriatic epidermal cells, dermal T cells and in blood samples, and plays a major role in psoriasis and correlates with an elevated TNF-α mRNA expression. miR-21 is involved in TGF-β1 signaling pathway regulation and downregulates metalloproteinase inhibitor-3 (TIMP-3) in keratinocytes. TIMP-3 inhibits the TNF-converting enzyme, a disintegrin and metalloprotease 17 (ADAM17), which converts the inactive form of TNF into its soluble, activated TNF configuration [69, 103–105, 118, 119, 122, 138].

miR-99a as well as mi-125b are specifically downregulated in psoriasis. Both are presented in dermal inflammatory infiltrates of psoriatic skin; they are also expressed in T helper type-17 (Th17) cells [127].

miR-99 is downregulated particularly in keratinocytes and the upper layer of the epidermis [104, 119, 125]. It targets IGF-1R, which enhances the proliferation of basal layer cells in patients with psoriasis, stimulating hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis [99].

miR-125b targets are FGFR-2, TNF-α, P63 and NOTCH1 genes. The diminished expression of such miRNAs consequently leads to an increased keratinocyte proliferation rate, together with altered differentiation and an upregulated inflammatory cascade by de-repressed mRNA for TNF-α (Table 3).

Serum miRNA level as a biomarker of disease prognosis and treatment

Serum levels of miR-33, miR-126, miR-223, and miR-143, among others, have been proposed as potential biomarkers of disease [114, 127]. miR-223 and miR-143 are found to be significantly correlated with the PASI (Psoriasis Area and Severity Index), suggesting their usefulness as biomarkers for disease severity in psoriasis [127].

Treatment of patients with methotrexate significantly decrease miR-223, and miR-143 in patients’ blood [127]. In another study, anti-TNF therapy significantly downregulates expression, in the blood of psoriatic patients, of miR0106, miR-26b, miR-142-3p, miR-223, and miR-126 [137].

These observations suggest that some serum miRNAs may serve as potential biomarkers for disease severity and therapy response in psoriasis. Some new data indicate usefulness of anti-miRNAs strategy in therapy of psoriasis.

miRNAs as the new therapeutic option in psoriasis

Many studies showed that modulating specific miRNAs had a therapeutic effect on keratinocytes [139]. Xu et al. reported that overexpression of miR-125b inhibited keratinocyte proliferation and promoted differentiation via inhibiting its direct target, FGFR2, in primary human keratinocytes [104]. Guinea-Viniegra et al., in an animal model has shown that anti-miR-21 has been to be effective in treating psoriasis. By contrast, it was identified that TGF-β1 could upregulate miR-31, while inhibition of miR-31 resulted in suppression of IL-1β and IL-8 in human primary keratinocytes [103]. Overexpression of miR-210 led to an increased proinflammatory cytokine (IFN-γ and IL-17) expression and decreased regulatory cytokine (IL-10 and TGF-β) expression in CD4+ T cells [115]. These experimental data provide important clues to help elucidate the pathogenesis of psoriasis and implicate that promotion of miR-125b while inhibition of miR-31 or miR-210 may also be potential therapeutic options to psoriasis [139, 140].

Genetic polymorphisms that affect miRNA activity might be relevant in the pathogenesis of psoriasis

Pivarcsi et al. in an excellent review summarize new information about the genetic polymorphisms which affect miRNA activity and have functional consequences to psoriasis pathogenesis. Authors suggested that alterations in miRNA-mediated gene regulation can contribute to psoriasis in the following ways:

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in psoriasis-associated miRNA genes can affect the activity of a miRNA, altering the set of targets regulated by it, or, interfering with its biogenesis.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms in the 3;′UTR of psoriasis-associated miRNAs can alter recognition by miRNAs (destruction or creation of miRNA binding sites).

RNA-editing resulting in miRNA isoforms (isomiRs) with an altered set of targets regulated by it.

Up- or downregulation of miRNAs due to epigenetic, transcriptional regulation or regulation of miRNA processing/stability may lead to disturbed gene regulation in psoriasis.

MiRNAs may serve as a new ‘language’ of intercellular communication in psoriasis [96].

SNPs in the primary transcripts of miRNAs – often long, up to 10 kb – are more likely to occur [117, 130]. Such miR-SNPs have been described to alter the efficiency by which the primary miRNA transcript is processed and thereby affects the level of the mature, biologically active miRNA.

IsomiRs, natural variations in miRNA ends due to RNA editing, is observed and recent sequencing studies revealed that a number of miRNAs, which are deregulated in psoriasis, such as miR-203, miR-21, miR-31, miR-142, miR-223 and miR-146 express also an altered variant in psoriasis as compared with healthy skin [131].

Many of the already identified SNPs in 3;′UTRs of genes associated with psoriasis in GWAS, such as HLA-C, IL-23A, LCE3D, TRAF3IP2, SOCS1 and others, potentially affect miRNA targeting by destroying, creating or altering miRNA binding to these genes.

To date, only one SNP within a miRNA binding site has been linked to psoriasis: a polymorphism abolishing a miR-492 binding site in the basigin gene has been shown to confer a psoriasis risk [135].

In conclusion, altered miRNA expression profiles are displayed in psoriasis. Although the exact roles of miRNAs in psoriasis have not been fully elucidated, a new layer of regulatory mechanisms mediated by miRNAs is revealed in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. miRNAs can regulate differentiation, proliferation and cytokine response of keratinocytes, activation and survival of T cells and the crosstalk between immunocytes and keratinocytes through the regulation of chemokine and cytokine production. Genetic polymorphisms in miRNAs or their target genes, affect miRNA activity and have functional consequences to psoriasis pathogenesis. Circulating miRNAs detected in the blood may become disease markers of diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of disease. The inhibition of expression by some miRNAs may be a new promising therapy option in psoriasis.

Conclusions

A huge progress in genotyping technologies in the “genomic era” confirms the polygenic character of psoriasis. More than 50 genetic susceptible markers are associated with the risk of psoriasis. The strongest association of disease with HLA-C*06 locus has been proved in different populations. The majority of psoriasis risk SNPs are situated near the genes encoding molecules involved in adaptive immunity, innate immunity and skin barrier function. Many contemporary studies indicate that epigenetic changes: histone modification, promoter methylations, long non-coding and micro-RNA hyperexpression are considered to be important in the pathogenesis of psoriasis as they regulate abnormal keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation, aberrant keratinocytes inflammatory cells communication, neoangiogenesis and chronic inflammation.