Introduction

Asthma has become a serious public health problem in the world, and results in a global prevalence ranging from 1% to 18% [1–3]. Its manifestations are derived from an underlying chronic inflammatory process mediated and orchestrated by products of certain immune cells [4–8]. However, no effective preventive measures or cure for asthma have been found, and current treatment aims to achieve and maintain clinical control. These methods may have no ability to suppress chronic inflammation and remodelling associated with asthma [9].

Many herbs have been developed for the treatment of asthma in human or animal models [10]. Nigella sativa has been used for many ailments for over 2000 years and has demonstrated the potential anti-asthmatic effects in the studies conducted in humans as well as animals [11–14]. It can provide relaxant effects on different smooth muscle preparations, anti-cholinergic effects, and an inhibitory effect on histamine receptors [13, 15, 16]. Furthermore, a previous study reported the anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory and anti-oxidant effects of Nigella sativa [17]. Some clinical studies have evaluated the effect of Nigella sativa on asthmatic patients and documented a significant improvement in subjective feelings and pulmonary function [18–20].

Current evidence is insufficient for routine clinical use of Nigella sativa supplementation in asthmatic patients. Recently, several studies have investigated the efficacy of Nigella sativa supplementation for these patients, but the results are conflicting [21–23].

Aim

This systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs aim to assess the efficacy of Nigella sativa supplementation in asthmatic patients.

Material and methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were performed based on the guidance of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis statement and Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [24–26]. No ethical approval and patient consent were required, because all analyses were based on previous published studies.

Literature search and selection criteria

We have systematically searched several databases including PubMed, Embase, Web of science, EBSCO, and the Cochrane library from inception to September 2019 with the following key words: Nigella sativa and asthma. The reference lists of retrieved studies and relevant reviews were also hand-searched and the above process was performed repeatedly in order to include additional eligible studies.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the study design was RCT, (2) patients were diagnosed with asthma, and (3) intervention treatments were Nigella sativa supplementation versus placebo.

Data extraction and outcome measures

Some baseline information was extracted from the original studies, and they included the first author, number of patients, age, female, body mass index and detailed methods in two groups. Data were extracted independently by two investigators, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. We have contacted the corresponding author to obtain the data when necessary.

The primary outcome was asthma control test (ACT) scores. Secondary outcomes included forced expiratory volume at 1 s (FEV1), peak expiratory flow (PEF), interleukin (IL)-4 and interferon γ (IFN-γ).

Quality assessment in individual studies

The methodological quality of each RCT was assessed by the Jadad Scale which consists of three evaluation elements: randomization (0–2 points), blinding (0–2 points), dropouts and withdrawals (0–1 points) [27]. One point would be allocated to each element if they were conducted and mentioned appropriately in the original article. The score of Jadad Scale varied from 0 to 5 points. An article with Jadad score ≤ 2 was considered to be of low quality. The study was thought to be of high quality if Jadad score ≥ 3 [26, 28].

Statistical analysis

We assessed standard mean differences (SMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for continuous outcomes (ACT scores, FEV1, PEF, IL-4 and IFN-γ). Heterogeneity was evaluated using the I2 statistic, and I2 > 50% indicated significant heterogeneity [29]. The random-effects model was used for all meta-analysis. We searched for potential sources of heterogeneity when encountering significant heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis was performed to detect the influence of a single study on the overall estimate via omitting one study in turn or performing the subgroup analysis. Owing to the limited number (< 10) of included studies, publication bias was not assessed. Results were considered as statistically significant for p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager Version 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Software Update, Oxford, UK).

Results

Literature search, study characteristics and quality assessment

Figure 1 shows the detailed flowchart of the search and selection results. Three hundred and fifteen potentially relevant articles are identified initially. Finally, four RCTs are included in the meta-analysis [20–23].

The baseline characteristics of four included RCTs are shown in Table 1. These studies were published between 2007 and 2017, and the total sample size is 187. The duration of Nigella sativa treatment ranges from 4 weeks to 3 months.

Table 1

Characteristics of included studies

Two studies report ACT scores [22, 23], three studies report FEV1 [20, 22, 23], two studies report PEF [20, 22], and two studies report IL-4 and IFN-γ [21, 23]. Jadad scores of the four included studies vary from 3 to 4, and all four studies have high quality based on the quality assessment.

Primary outcome: ACT scores

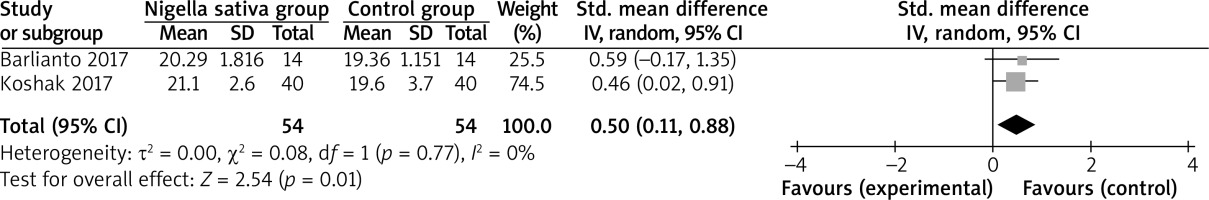

The random-effects model is used for the analysis of primary outcomes. The results have found that compared to the control group, Nigella sativa supplementation is associated with increased ACT scores (SMD = 0.50; 95% CI: 0.11–0.88; p = 0.01), with no heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 0%, heterogeneity p = 0.77, Figure 2).

Sensitivity analysis

There is no heterogeneity for ACT scores, and thus we do not perform sensitivity analysis by omitting one study in each turn to detect the source of heterogeneity.

Secondary outcomes

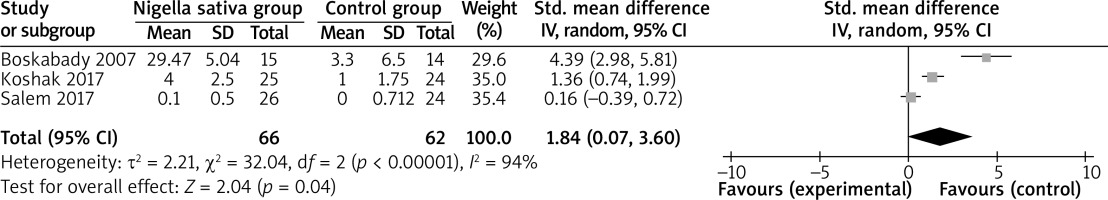

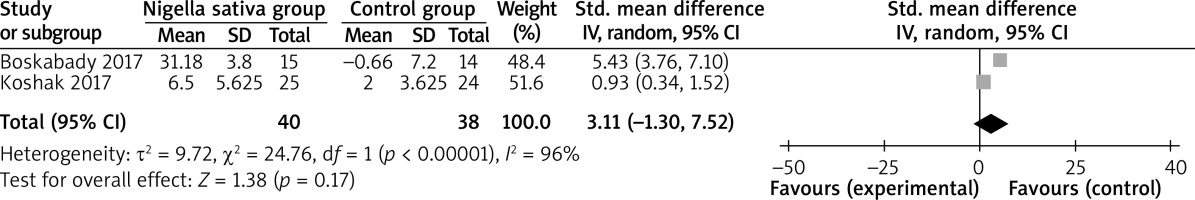

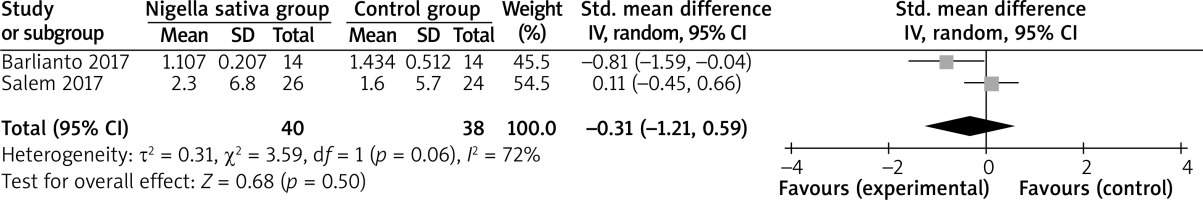

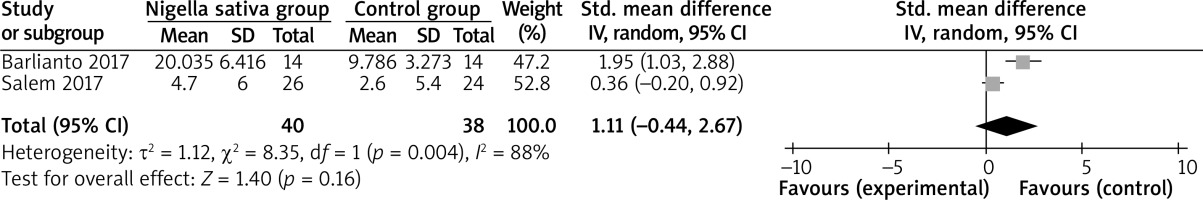

In comparison with control intervention for asthma, Nigella sativa supplementation can substantially increase FEV1 (SMD = 1.84; 95% CI: 0.07–3.60; p = 0.04; Figure 3), but shows no obvious impact on PEF (SMD = 3.11; 95% CI: –1.30 to 7.52; p = 0.17; Figure 4), IL-4 (SMD = –0.31; 95% CI: –1.21 to 0.59; p = 0.50; Figure 5), or IFN-γ (SMD = 1.11; 95% CI: –0.44 to 2.67; p = 0.16; Figure 6).

Discussion

Many studies have documented the Nigella sativa supplementation for the control of bronchial asthma, and revealed the positive effects on different aspects of asthma control like clinical outcome, pulmonary function tests, cytokines, IgE and FeNO [18, 30, 31]. Previous studies reported a favourable effect of Nigella sativa on lung function tests in asthmatic patients suggesting the potential bronchodilator effect of Nigella sativa [18].

The ACT score includes items on shortness of breath, night time waking, interference with activity, rescue treatment use and rating of asthma control. It has been validated to evaluate the degree of control of asthma by using the ACT score [32]. Our meta-analysis suggests that Nigella sativa supplementation can substantially improve ACT scores and FEV1 in asthmatic patients, but has no effect on PEF. However, Nigella sativa supplementation was revealed to specifically improve expiratory flow during the mid-part of vital capacity (FEF 25–75%) [21] indicating the benefits for the function of the small airways [33].

The pathogenesis of bronchial asthma is associated with an underlying chronic inflammatory process determined by a balance of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators. IL-4 (produced by Th2) and IFN-γ (produced by Th1) are representative of these two groups. IL-4 indicates the increased inflammation while IFN-γ has the opposite effect [34]. One trial revealed that IFN-γ was increased by Nigella sativa [21]. The decrease in IL-4 and increase in IFN-γ is observed for Nigella sativa treatment for asthmatic patients in our meta-analysis, but there is no statistical difference. These imply that Nigella sativa may support the anti-inflammatory effect.

Administration of Nigella sativa to patients with asthma was associated with a reduction in FeNO [21], an indicator of the inflammatory reaction underlying pathogenesis of bronchial asthma [35]. This efficacy was observed at the 1 g dose of Nigella sativa, but disappeared at the 2 g dose, which suggested that Nigella sativa might have been maximally active against NO production at 1 g/day dosage, but the effect was minimized at higher doses [21]. Several studies have found that Nigella sativa was well tolerated, and only mild and self-limited side effects were reported [21, 22].

Several limitations exist in this meta-analysis. Firstly, our analysis is based on four RCTs only, and more RCTs with a large sample size should be conducted to explore this issue further. Next, although there is no heterogeneity for the ACT scores, different treatment duration and age range of patients may lead to some bias. Finally, it is not feasible to perform the analysis of some outcomes such as exacerbation, FVC or FeNO based on currently included RCTs.