Introduction

Dermatological diseases are particularly prone to affect quality of life because of the role that skin has in people’s lives [1]. Any abnormalities are noticed immediately by others and play a huge part in forming first impressions of a person, including physical attraction [2]. Diseases that affect the skin are often difficult to hide and can prompt negative reactions from others. Such negative reactions generate much stress for the affected individuals, impairing their quality of life whilst impacting various activities and interpersonal relationships [3]. Itch and other subjective symptoms frequently coexist with skin conditions causing a decline in mental health for individuals [4]. All of the above-mentioned factors reduce dermatological patients’ psychological well-being and can lead to development of psychiatric disorders [5].

Adolescence is a specific time period in an individual’s development. It differs from childhood and adulthood and is the time when young people are especially prone to the negative impact a disease may have on their quality of life.

Several questionnaires are available to assess quality of life impairment in different age groups of dermatological patients [6–8]. These tools are very important in clinical practice as well as in research, including clinical trials [9]. They help measure the impact of a disease on a patient’s life in a standardized way. The Teenagers Quality of Life questionnaire (T-QoL) is a short and easy questionnaire designed specifically for teenagers with skin disorders to measure current impact of the skin diseases on their quality of life. What is really important it was created using direct input from the target group of patients. The questionnaire was already successfully translated into several language versions [10]. This, in turn, enables the doctor to compare disease activity at different time points in order to detect flares or to assess treatment response. Questionnaires should be translated into local languages where possible to ensure ongoing questionnaire validity and relevance of the key concepts.

Aim

The aim of this study was to translate and further validate the Teenagers Quality of Life (T-QoL) questionnaire in order to provide a Polish language version, which is a tool used for assessing quality of life impairment among patients in this specific age group affected by dermatological disorders.

Material and methods

Translation and validation process

The Polish translation of the T-QoL questionnaire was made following the guidelines set by the Cardiff University. At the very beginning of the process two independent forward translations were prepared. Then a harmonized translation was prepared by a third consultant, an expert who is fluent in both Polish and English languages, to look for any discrepancies between the translations. The next step was to create two separate back translations of the harmonized Polish version of the survey. These English versions were presented to a questionnaire creating team member, who made their suggestions on some minor changes to prepare an accurate final Polish version of the T-QoL questionnaire.

Cognitive debriefing was performed with a total of eight people. Interviewees were four females and four males suffering from different dermatological conditions (three acne, two urticaria, one perifolliculitis capitis abscedens et suffodiens, one lichen planopilaris, one atopic dermatitis) aged 12–19 years (mean: 14.5). They were also asked to make suggestions for changing the wording of the questions and answer categories to make them clearer and easier to understand.

Then the Polish version of T-QoL was distributed among 34 teenage dermatological patients in total. The study group consisted of 16 males and 18 females, aged from 12 to 19 years (mean age: 15.2 years), 20 were under the age of 16 years. Participants suffered from various dermatological diseases such as acne vulgaris (n = 12), atopic dermatitis (n = 8), psoriasis (n = 3), eczema (n = 3), urticaria (n = 2), lichen planopilaris (n = 1), hidradenitis suppurativa (n = 1), perifolliculitis capitis abscedens et suffodiens (n = 1), morphea (n = 1), and dermatitis perioralis (n = 1). All of them were asked to complete the T-QoL questionnaire as well as the DLQI, if the person was 16 or older, or the CDLQI, if the person was under 16 years old. These instruments had been used to check validity of the T-QoL while creating the original version [10]. Participants were asked to complete the Polish language version of the T-QoL twice. The second completion took place 3-5 days after the first one.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics v.26 (SPSS INC., Chicago, USA) software. The reliability of the Polish version of T-QoL was evaluated by conducting a statistical analysis of the data. The level of statistical significance was assumed at a 2-sided p-value of < 0.05. In order to check the overall internal consistency of the questionnaire, Cronbach α coefficient was used. Values of Cronbach α above 0.9 were considered as excellent internal consistency, and above 0.7 as acceptable internal consistency [11]. The interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to evaluate the reproducibility of the questionnaire (test-retest reliability). ICC values > 0.80, 0.60–0.80, 0.40–0.60, and < 0.40 reflected excellent, good, moderate, and poor levels of reliability, respectively [12].

The convergent and construct validity of the Polish version of T-QoL was evaluated by requesting participants to complete translated forms along with DLQI or CDLQI. In order to assess the convergent validity of the Polish version of T-QoL, Pearson’s correlation was used [13]. It was also evaluated by means of Pearson’s correlation coefficient to check dependencies between the Polish translation of the T-QoL and the DLQI in patients aged 16–19 years and the CDLQI in patients aged under 16 years. Lastly, Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to identify differences between answers given by the participants to each question on days 1 and 3-5. This time period ensured that the skin condition severity had not changed significantly but, at the same time, reduced the chances of remembering prior answers.

Results

The time needed to complete the questionnaire averaged slightly under 7 min (range: 2–10 min). After completing the form, respondents assessed the intelligibility and wording of each question. None of the respondents reported any problems concerning the understanding of questions or categories and did not submit any suggestions on changing the wording of questions or categories.

Consequently, the Polish translation of the T-QoL questionnaire was accepted as a good equivalent to the original English version. This official Polish language version of the T-QoL is now available on the website of Cardiff University (https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/medicine/resources/quality-of-life-questionnaires/teenagers-quality-of-life).

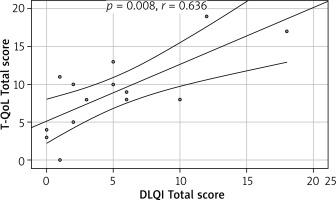

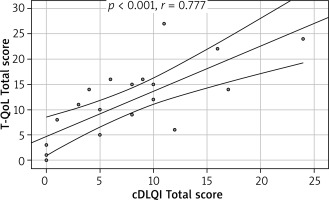

Fourteen (41%) patients completed the DLQI and 20 (59%) patients the CDLQI. The Polish version of the T-QoL is internally consistent, with Cronbach α = 0.893 for the whole questionnaire. It has excellent convergent validity with an ICC value of 0.864. First and second (after 3–5 days) completions of the T-QoL were comparable with no statistically significant differences noticeable between each question (Table 1). T-QoL scores correlated significantly with the DLQI (p = 0.008, r = 0.636) (Figure 1) and CDLQI (p < 0.001, r = 0.777) (Figure 2) scores.

Table 1

Correlation between 1st and 2nd assessments of the Teenagers Quality of Life questionnaire

Discussion

People are especially prone to stress when they are teenagers as the brain is undergoing substantial neurodevelopmental and personality changes [14]. Adolescence itself generates a lot of pressure due to life’s many changes, including but not limited to body changes, new relationships and future planning [15]. Knowing that childhood and adolescence are two different periods, using the same instrument to measure quality of life impairment for those groups can sometimes be misleading [16]. Instruments such as the CDLQI may be used amongst teenagers but are not specific to this group [7]. There are also instruments age specific such as Skindex-Teen but not all language versions may be available [17]. The Skindex-Teen differs from the T-QoL because it is more complex and takes more time to fulfil the questionnaire [10]. Creating other language versions and further contributing to the validation process is therefore vital to constantly improve and widen the range of tools available to measure quality of life impairment. Using such instruments gives physicians the ability to fully understand the burden of the disease and better manage patients [6]. Developing new questionnaires enables researchers to create more specific questions for adolescence [10]. After performing the validity process it is possible to conclude that the Polish version of T-QoL, proposed for use in dermatological patients 12–19 years old, is an internally consistent, reliable questionnaire with adequate construct validity. This new questionnaire dedicated to assessing teenagers’ quality of life includes questions about different life aspects such as body image, physical well-being, future aspirations and influence of the skin disease on the patient’s mental status and relationships [10]. All of these are important to be considered when quality of life is measured [18]. During the cognitive debriefing participants found the Polish version of the questionnaire easy and quick to complete. The lack of negative comments from the participants provides reassurance that it is a well-understood, relevant and patient-friendly measure. The correlation between the CDLQI/DLQI and the Polish language version of T-QoL was strong, providing further encouragement for researchers and physicians in using this tool. Comparable results were obtained for the original version as well as other language versions [10, 19]. Other researchers have also compared the T-QoL to different questionnaires such as Skindex-Teen or Global Question (GQ) with excellent results [10, 19]. T-QoL may capture some of the prevalent issues with teenagers’ mental health that may be brought on by chronic skin disease, considerably influencing their future lives [15]. A limitation of the study is the small group size, although the sample number utilized is generally considered to be enough to perform valid statistical analysis [20]. In future research, the newly translated instrument could be compared with some disease specific questionnaires to compare its usefulness [21].

Conclusions

This study shows that the Polish language version of the T-QoL is an excellent tool that can be used to measure quality of life of dermatological patients aged from 12 to 19 years old. The questionnaire’s internal consistency and test-retest reliability were satisfactory. As demonstrated by the adequate convergent validity, consistency and reproducibility, the Polish version of the T-QoL questionnaire is a reliable instrument that may be used to assess current quality of life impairment among teenagers. Taking that into consideration it can be proposed to use in clinical practice as well as for future research involving patients suffering from various skin conditions, helping physicians and scientists understand skin disease impact on patients’ lives.