Purpose

Primary vaginal cancers are rare, comprising 1-2% of all gynecological malignancies and mostly seen at the age of 60-70 years [1]. These tumors usually occur in the upper one-third of the vagina, and squamous cell carcinoma is the most common histological type. Similar to vaginal cancer, pelvic organ prolapse (POP) has a peak prevalence of 5.1% in women aged 60-69 years [2]. Vaginal trauma, chronic irritation, and inflammation of the vaginal mucosa can cause primary vaginal cancer in patients with POP [3]. However, a combination of POP and primary vaginal or cervical cancer is an extremely rare entity [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19].

Multidisciplinary management is necessary for optimal treatment of primary vaginal cancer. While surgery can be performed in early stage disease, definitive chemoradiotherapy (CRT) is the preferred treatment for the advanced stage. In this case, we report a 77-year-old woman with a diagnosis of primary vaginal cancer associated with a reducible POP. She was treated with definitive CRT and brachytherapy (BT) after using a pessary to restore vaginal anatomy for optimal radiation.

Case report

A 77-year-old women, gravida 4, parity 4, presented with a 7-month history of vaginal bleeding. She had a clinical history of total abdominal hysterectomy due to multiple uterine leiomyomas 40 years ago and she had vaginal vault prolapse for 13 years with no history of pessary use. Her medical history included hypertension and ischemic heart disease. Physical examination revealed manually reducible stage 4 vaginal vault prolapse according to the POP quantification system [20], with an infiltrating 1-2 cm mass between the upper and middle third of the posterior vaginal wall. There was no parametrial invasion, pelvic wall involvement, or inguinal lymph node metastases (Figure 1).

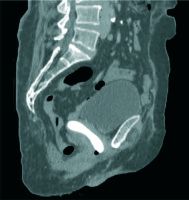

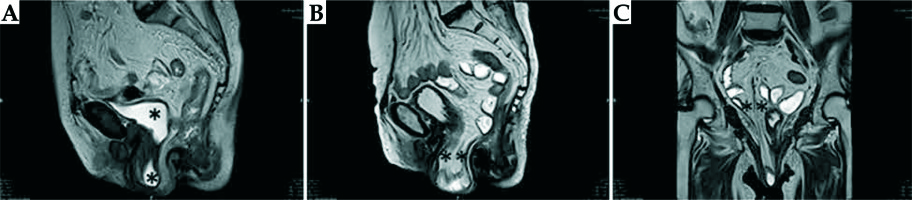

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed tricompartmental (cystocele, enterocele, and vaginal vault) POP, but no visible tumor (Figure 2). Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) revealed high F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the primary vaginal mass (SUVmax, 16.37) without any evidence of metastases to the lymph nodes or other organs (Figure 3). Incisional biopsy from the lesion was reported as squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina.

Fig. 2

A) Sagittal T2-weighted (W) image of the pelvic MRI shows cystocele. B, C) Sagittal and coronal T2-weighted (W) images of the pelvic MRI show enterocele with ileal segments and mesentery. All images were obtained in static imaging without Valsalva’s maneuver (*bladder, **ileal segments, and mesentery)

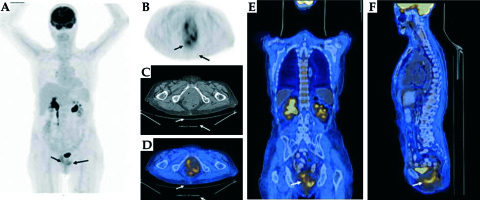

Fig. 3

FDG PET/CT images show increased bilateral uptake in the thickened posterior vaginal wall with an SUVmax of 16.37. A) Maximum intensity projection images (MIP). B-F) FDG PET, CT, axial, coronal, and sagittal fusion images (arrows)

She had primary vaginal cancer staged as FIGO stage II, and definitive CRT was planned [21]. External beam radiotherapy (EBRT) was given in 28 fractions of 1.8 Gy via intensity-modulated RT (IMRT) technique, with concurrent 6 cycles of 40 mg/m2 weekly cisplatin (Figure 4A). The primary clinical target volume (CTV) included gross tumor volume (GTV), which was expanded by 1-2 cm margin, entire length of the vagina, and paravaginal tissue. The lymphatic CTV contained the external iliac, internal iliac, presacral, obturator, and inguinal lymph node regions. The CTV was expanded by 1 cm to form planning target volume (PTV). Bladder, rectum, sigmoid colon, and bowel were delineated as organs at risks (OARs). Before EBRT, silicone ring pessary without central support diaphragm (size 3, 2.50” 64 mm) was placed into the vagina to help reposition and support the prolapsed vagina, to immobilize the radiation field, and to reduce prolapse symptoms (Figure 5). The pessary was left in place until EBRT was completed. At the end of the EBRT, the pessary was removed. Vaginal examination revealed a complete response (Figure 6). After clinical confirmation of complete response, high-dose-rate (HDR) CT-guided vaginal cuff BT was performed, with a dose of 26 Gy in 4 fractions prescribed to the full thickness of the vaginal wall (Figure 4B). Total (EBRT + BT) biologically equivalent dose in 2 Gy fractions (EQD2) were calculated with α/β = 10 Gy for tumor and α/β = 3 Gy for late-responding tissues using the linear quadratic model [22]. The total cumulative doses were as follows: primary CTV = 85.3 Gy, rectum D2cm3 = 69.9 Gy, sigmoid D2cm3 = 57.5 Gy, bladder D2cm3 = 76.9 Gy.

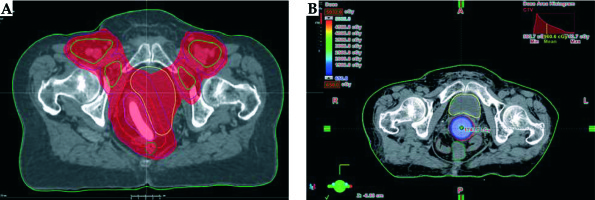

Fig. 4

A) Axial image of CT simulation for radiation therapy and 95% dose color wash of IMRT treatment planning. B) Axial image of CT simulation for HDR brachytherapy. The gross tumor volume (red line) was well covered by the prescribed 6.5 Gy isodose line

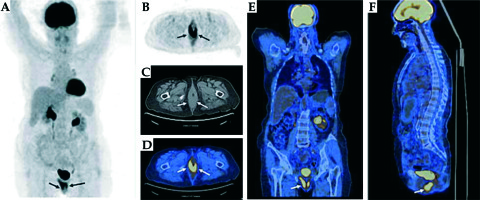

Treatment was well tolerated. During CRT, grade 3 hematologic toxicity was observed and treated with blood transfusions. Grade 2 dermatitis in the vulva was observed at the end of treatment and was treated with topical agents (Figure 7). The patient had no severe complaints other than mild vaginal pain. At 3-months follow-up, although vaginal examination showed complete response (Figure 8), PET/CT revealed high F-18 FDG uptake in the region of primary vaginal mass (SUVmax, 5.7) compatible with partial response (Figure 9). A biopsy was performed to exclude recurrence or residual disease and the complete response was confirmed. She is still alive without disease at 10-months follow-up. However, the patient experienced symptoms like vaginal dryness, itching, and burning possibly due to POP and vaginal atrophy. She refused to undergo prolapse surgery consisting of sacrocolpopexy. Ring pessary was placed again into her vagina, and topical estrogen cream was prescribed to alleviate her complaints and to maintain a healthy vaginal epithelium.

Fig. 9

FDG PET/CT images after chemoradiotherapy showed decreased FDG uptake (SUVmax from 16.5 to 5.3) in the vaginal wall compatible with the residual tumor or post-therapy inflammatory changes. A) Maximum intensity projection images (MIP). B-F) FDG PET, CT, axial, coronal, and sagittal fusion images (arrows)

Discussion

Primary vaginal cancer is a rare malignancy and mostly seen in elderly people [1]. The most common risk factors for primary vaginal cancer include human papillomavirus (HPV), history of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, immunosuppression, multiple sexual partners, smoking, early age at first intercourse, low socioeconomic status, history of genital warts, and vaginal trauma [3,23,24]. Chronic irritation and inflammation of the vaginal mucosa may also cause primary vaginal cancer.

Pelvic organ prolapse is defined as the descent of female pelvic organs, including the bladder, uterus or post-hysterectomy vaginal cuff, and the small or large bowel [25]. The etiology of prolapse is multifactorial and includes advancing age, increased parity, menopause, collagen weakness, pelvic floor denervation, and direct trauma to the pelvic floor during surgery and deliveries [26]. POP leads to chronic mechanical irritation and adversely affects the quality of life (QoL). Rarely, as seen in our patient, due to chronic irritation, primary vaginal cancer may develop secondary to prolonged POP. However, primary vaginal or cervical cancer and POP combination is rarely reported in the literature [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. The increase in the incidence of both POP and primary vaginal cancer with advancing age makes this combination more frequent in elderly people [1].

There are no clear treatment recommendations in combined POP and primary vaginal cancer. When the early stage primary vaginal cancer is combined with POP, surgery becomes the first option instead of RT to cure primary disease and also to restore the anatomy [4,5,6,7,8,11,12,13]. Interstitial BT is another treatment option for medically inoperable patients with early-stage disease [19]. However, RT or CRT are the primary choice of treatment for most patients with locally advanced disease, and usually requires careful integration of EBRT and vaginal BT [6,9,10,27,28]. When applying EBRT in cases with combined POP and vaginal cancer, critical organ doses may result in larger than expected dose due to the downward descent of the pelvic organs. Additionally, high complication rates in these patients have been reported in the literature [10,17]. Rao et al. reported that two of 5 patients developed vesicovaginal fistula following definitive EBRT [10]. Reimer et al. used neoadjuvant CRT and vaginal BT for the cervical cancer patient with irreducible uterovaginal prolapse [17]. Hemorrhagic cystitis could not be avoided after an administered dose of 36 Gy EBRT in this patient.

Pessaries are devices that are placed into the vagina to restore pelvic anatomy and decrease prolapse symptoms [4]. Currently, using of pessary is the only available, non-surgical intervention especially for high-risk surgical candidates with POP, and is reported to relieve prolapse and urinary symptoms, improving health-related QoL. However, using of pessary can also cause serious complications as bleeding and ulceration, and special care should be taken during this treatment [29]. Recently, Dawkins et al. reported a case of 72-year-old woman with cervical cancer with POP, and she was treated with definitive CRT and BT [18]. Gelhorn pessary was placed and perineoplasty was performed before EBRT to reduce POP, and the authors reported no treatment-related side effects.

In our case, definitive CRT was applied, since she had locally advanced disease and she was not suitable for surgery. Before definitive CRT, a ring pessary was placed in order to prevent further increase of POP-related symptoms due to CRT. She tolerated the treatment very well. To our knowledge, presented case is the first case of having definitive CRT with using a pessary who had both vaginal cancer and POP. This treatment approach may limit the risk of genitourinary and gastrointestinal complications due to restoring the anatomy, and reducing radiation exposure to the bladder, rectum, and bowel. It also decreases vaginal irritation and ulceration due to friction during EBRT and may improve patient’s QoL. Alternatively, prolapse surgery may be undertaken before CRT, even though the recovery period after surgery may cause delays for definitive treatment. In addition, pessary use seems to be a good option in patients who could not be operated due to comorbid diseases like our patient.

In conclusion, especially in elderly patients, the pessary is well tolerated during definitive CRT, and it is a non-surgical procedure to restore the anatomy for symptom relief and to provide more precise RT.