Introduction

Until the mid-20th century, the leading causes of death were acute illnesses, particularly infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, peritonitis, and pneumonia, often affecting children. Advances in medicine, improved living conditions, widespread immunizations, and the development of antibiotics and antibacterial drugs significantly reduced mortality from these conditions [1,2,3].

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is now a global health challenge. A meta-analysis of observational studies estimated that approximately 13.4% of the world’s population suffers from CKD, with 79% of these individuals in the later stages of the disease (stages 3–5). The true prevalence of early-stage CKD (stages 1–2) is likely much higher, as it often remains asymptomatic in its early phases. The increasing prevalence of CKD is attributed to population aging and the growing incidence of type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases, all of which contribute to its development [4,5].

In modern times, chronic diseases have surpassed acute illnesses as the most common causes of death. factors such as unhealthy lifestyles, physical inactivity, poor diets, substance use, and increasing environmental pollution contribute to this shift. Advances in medical care have transformed many previously fatal diseases into chronic conditions through effective treatments and medications. Chronic kidney disease, in particular, has become a prominent example of this trend [6].

CKD is a syndrome characterized by a slow but irreversible decline in kidney function. This progressive deterioration ultimately necessitates renal replacement therapy, such as dialysis. for patients, this creates a difficult situation that often tests their ability to cope. Individual responses to the disease depend on psychological and physical characteristics, personal life experiences, upbringing, social environment, and living circumstances [2,3].

The disease manifests as a gradual loss of functional nephrons due to pathological processes in the renal parenchyma. CKD is often asymptomatic in its early stages or presents only mild symptoms, which can delay diagnosis until the disease has advanced significantly [2,4]. Even at later stages, symptoms may develop slowly, allowing patients to adapt over time. Consequently, CKD is frequently diagnosed incidentally during its final, severe stages, when immediate renal replacement therapy becomes necessary [7].

Chronic renal failure is characterized by alternating periods of exacerbation and remission. Although it cannot be cured, dialysis therapy can extend life. However, this treatment imposes significant demands on patients, such as persistent symptoms, dietary restrictions, and the need to adhere to a strict dialysis schedule—typically three times a week for 5–6 hours per session. These challenges can disrupt daily plans and activities, creating frustration and distress. Patients often rely on psychological defense mechanisms such as denial, suppression, or acceptance to cope emotionally. Among these, acceptance is the most beneficial, as it facilitates better cooperation with healthcare providers [8,9,10].

The most common defense mechanisms used by patients include denial, suppression, humiliation, and acceptance. from a therapeutic perspective, acceptance of the diagnosis is the most desirable and beneficial mechanism, as it ensures cooperation with the healthcare team. Chronic illness often leaves patients feeling deprived of freedom or restricted in their autonomy. for dialysis patients, their lives are closely tied to the specifics of their treatment. On average, they must visit the dialysis center three times a week, spending approximately 5–6 hours per session. In addition to this time commitment, they must adhere to a strict diet, practice self-care, monitor their condition, and self-administer medications [11,12].

A person’s response to an illness, particularly a chronic one, depends on several factors. The type and severity of the disease, educational background, and life experiences all play a role. Many patients experience distinct phases in their attitudes toward their illness, often triggered by the stress of diagnosis [13].

Chronic illness also significantly alters family dynamics and functions. Dialysis patients face limitations in their ability to perform daily tasks, stemming both from the symptoms of their underlying condition and the demands of dialysis therapy. The necessity of frequent visits to the dialysis center disrupts the previous balance of roles within the family. This often results in a shift in caregiving responsibilities and emotional support, with significant changes to family members’ roles [14,15].

The time consumed by dialysis treatments encroaches on leisure and family time, often leading to conflict, frustration, guilt, and depression among family members. Patients are sometimes perceived by family and friends as having limited prospects for their future, which may intensify feelings of helplessness and strain within relationships. families often struggle to express anger or other negative emotions constructively. Nurses can play a crucial role in this context by normalizing these emotional responses and educating family members on where to seek information and support. Including family members in treatment decisions can further foster a sense of involvement and shared responsibility [16].

The patient’s ability to participate in cultural and social activities also diminishes due to declining health, the physical and emotional toll of hemodialysis therapy, dietary restrictions, and financial challenges. Many patients experience feelings of social alienation and a loss of purpose, particularly if they are forced to reduce or abandon their professional roles. Consequently, enabling dialysis patients to maintain employment, pursue education, or explore personal interests becomes an essential strategy for improving their overall quality of life [17].

A chronic illness in itself evokes negative tensions and emotions. The life of a patient affected by a serious condition is marked by a lower quality of life. Scientific studies indicate that objective indicators of life quality do not clearly translate into the level of disease acceptance [18].

The long-term nature of chronic illnesses and their treatments imposes numerous challenges on patients and their families. These challenges include disruptions to daily routines, difficulties in adapting to new roles, and emotional stress. Chronic conditions require a dual approach: professional medical care to address the physical aspects of the disease and psychological support to help patients and their families adapt to their new circumstances. Medical interventions are typically episodic, occurring during acute phases or disease flare-ups, often within a hospital setting. In contrast, psychological support should be continuous, encompassing all aspects of the patient’s life, especially during periods of disease remission. This is essential, as individuals vary widely in their ability to cope with chronic illness [17,19].

The aim of this paper was to examine the relationship between acceptance of the disease and satisfaction with nursing care among dialysis patients with chronic kidney disease.

Material and methods

The survey was conducted among 110 randomly selected patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing dialysis therapy. The survey was administered online using a form created on Google Drive and distributed via online forums managed by individuals living with chronic kidney disease or other kidney-related conditions. Participants were asked to complete the survey honestly. The survey was anonymous, and the collected data was used for analysis, hypothesis verification, and formulation of conclusions.

The study employed a diagnostic survey method. The research tools included a proprietary questionnaire and the Acceptance of Illness Scale (AIS), which measures the degree of illness acceptance. The higher the level of acceptance, the better the adaptation to the illness and the lower the psychological discomfort. Responses were ranked using a point-based scale (“strongly agree” — 1, “strongly disagree” — 5). A score of 1 indicated poor adaptation to the illness, whereas a score of 5 represented a high level of acceptance. The total score from eight questionnaire items served as a measure of the degree of acceptance of the respondent’s health condition. The minimum possible score was 8, and the maximum was 40 [20].

Satisfaction with nursing care was assessed based on responses to seven questions in the survey questionnaire. Respondents were asked to evaluate eight statements concerning various aspects of nursing care by assigning each a score from 1 to 5, where 1 indicated strong agreement and 5 indicated strong disagreement. To measure patient satisfaction with nursing care, the scale was reversed prior to scoring. Thus, the total score from the responses ranged from a minimum of 7 to a maximum of 35. Due to the reversed scale, a higher score corresponded to a higher level of satisfaction with nursing care.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using descriptive and inferential statistical methods. The study group and the results derived from survey responses were characterized using the absolute number of responses (n) and structural indicators (%). Among inferential statistical methods, the χ2 independence test and structure indicator test were used.

Hypotheses were tested at a significance level of α = 0.05. Data analysis was carried out using the Statistica 13 software package and the Excel spreadsheet from Office 365.

Results

1.1. Characteristics of the study group

The study group consisted of 110 patients of various ages undergoing dialysis due to chronic kidney disease. Women slightly outnumbered men in the group, accounting for 50.9%. The largest age group was 61–75 years old, comprising 39.1% of respondents. This was followed by 41–60-year-olds (32.7%). Additionally, 17.3% of respondents were aged 18–40, and 10.9% were aged 76 or older.

In terms of education, the group was dominated by individuals with secondary (39.1%) and vocational education (30.9%). Others had higher education (22.7%) or primary education (7.3%). The largest proportion of respondents (41.8%) had been undergoing dialysis for 3–5 years. About one-third (32.7%) had been treated for more than 5 years, while 25.5% had been in therapy for 1–2 years.

1.2. Acceptance of the disease - AIS scale

Most respondents (60.0%) rated their dialysis therapy positively, with 27.3% rating it very positively. Only 8.2% expressed negative opinions (6.4% rated it as “poor,” and 1.8% as “very poor”), while 4.5% had no opinion on the matter.

Regarding their health condition, the majority of respondents rated it as good (37.3%) or satisfactory (35.5%). Others described it as very good (13.6%), slightly unsatisfactory (11.1%), or completely unsatisfactory (2.5%). Nearly half of the respondents (44.5%) indicated that their health condition had not changed significantly over the past year. A quarter (25.5%) noted slight improvement, while 18.2% described it as slightly worse. Additionally, 9.1% reported significant improvement, and 2.7% indicated a significant deterioration (Figure 1).

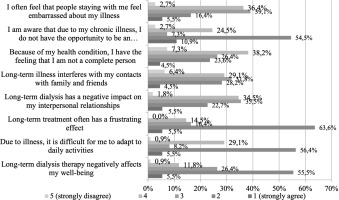

Respondents were asked to evaluate eight statements about their current condition, rating each on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 indicated strong agreement with the statement and 5 indicated strong disagreement.

The statement, “I am aware that due to my chronic illness, I do not have the opportunity to be an independent person like I was before my illness,” received the highest percentage of ratings as 1 (10.9%). In contrast, the statement, “Because of my health condition, I have the feeling that I am not a complete person,” received the most ratings as 5 (7.3%), followed closely by “Long-term illness interferes with my contacts with family and friends” (6.4%).

The mean score in the study group was 21.7 ± 5.4, with a median score of 21. The respondent most accepting of their illness scored 38. The results showed that the majority of respondents (62.7%) demonstrated a moderate level of acceptance. Meanwhile, 27.3% of respondents did not accept their condition at all, and 10.0% exhibited a high level of acceptance.

The study found a statistically significant relationship between dialysis patients’ subjective assessment of their health and their level of disease acceptance (p = 0.011). As acceptance levels increased, so did the percentage of respondents who rated their health as good or very good (Table 1).

Table 1

Subjective evaluation of the health status of dialysis patients according to the of their acceptance of the disease.

1.3. Satisfaction with nursing care

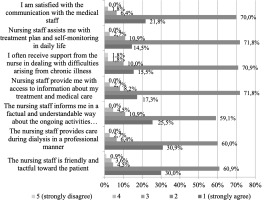

The statements, “The nursing staff provides care during dialysis in a professional manner” (30.9%) and “The nursing staff is friendly and tactful toward the patient” (30.0%), received the most ratings of 1, reflecting a high level of agreement. Conversely, the statement, “I often receive support from the nurse in dealing with difficulties arising from chronic illness” received the highest percentage of ratings as 5 (1.8%).

The mean value of this indicator in the studied group was 28.5 ± 3.4, with a median of 28. The respondent who rated nursing care the lowest assigned it 14 points, while the highest score awarded was 35 points.

To determine the level of nursing care, three score intervals were established. A score ranging from 7 to 21 was interpreted as a low rating of nursing care, 22 to 28 as an average rating, and 29 to 35 as a high rating. More than half of the respondents (50.9%) assessed the level of nursing care they received as average, while a further 45.5% considered it high. Only 3.6% of the respondents rated the nursing care provided to them as low (Figure 2).

The study did not find a statistically significant relationship between the degree of acceptance of the disease by dialysis patients and the quality of nursing care they received (p = 0.732) (Table 2).

Table 2

Degree of acceptance of disease by dialysis patients according to level of nursing care.

| Degree of acceptance of disease | Level of nursing care | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Mediocre | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| No acceptance | 15 | 25.0 | 15 | 30.0 | |

| Moderate acceptance | 38 | 63.3 | 31 | 62.0 | |

| High acceptance | 7 | 11.7 | 4 | 8.0 | |

| Tota | l | 60 | 100.0 | 50 | 100.0 |

| p | 0.732 | ||||

The study revealed that dialysis patients’ self-assessment of changes in their health over the past twelve months is statistically significantly influenced by the level of nursing care they receive (p < 0.001). As the quality of nursing care improves, the percentage of patients reporting a better perception of their health changes over the past year also increases. This finding underscores the critical role of professional and compassionate nursing care in positively shaping patients’ perspectives on their health outcomes.

Discussion

The impact of chronic dialysis on the lives of patients has been explored by many institutions and researchers from both medical and psychosocial perspectives. Leading organizations, including the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI), which develops guidelines for kidney disease treatment with a focus on dialysis, and the Renal Physicians Association (RPA), which conducts research on various aspects of dialysis, including its effects on patients’ daily lives, have contributed to this body of work. The Polish Society of Nephrology (PTN) also plays a significant role by publishing research and hosting conferences on kidney disease treatment, including dialysis.

A study conducted by Mushtaque et al. among patients with chronic kidney disease during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that a lower sense of satisfaction with nursing care was associated with a lower level of illness acceptance [21].

In the present study, the majority of respondents demonstrated a moderate level of illness acceptance. The average score on the Acceptance of Illness Scale (AIS) within the study group was 21.7 ± 5.4 out of a possible 40 points. A statistically significant relationship was observed between patients’ subjective assessment of their health status and the degree to which they accepted their illness.

Similar findings were reported by Hamerlińska and Kamyk-Wawryszuk. In their study involving individuals with rare diseases, the mean AIS score was 26.41 points, indicating a moderate level of illness acceptance. The standard deviation accounted for over 33.09% of the mean value, suggesting a high variability in AIS scores. Illness acceptance among women (mean: 27.00) was slightly higher than among men. Among the various dimensions of illness acceptance, respondents reported relatively little embarrassment due to their condition (mean: 3.65), a sense of being needed (mean: 3.41), and a belief in their own worth as individuals (mean: 3.46). The most significant factors negatively affecting illness acceptance were the awareness that they would never be as self-sufficient as they desired (mean: 2.7) and the perception that their health issues made them more dependent on others than they wished to be [22].

In the study conducted by Ponczek et al., the mean AIS score was 24.89 points, also indicating a moderate level of illness acceptance. The standard deviation accounted for over 34.9% of the mean value, reflecting a considerable variation in acceptance levels. Among the socio-demographic factors, age and duration of illness had a significant impact. Higher levels of illness acceptance were observed in younger individuals and those with a shorter duration of illness, whereas lower levels were reported among individuals over the age of 65 [23].

Few authors have investigated the potential relationship between hemodialysis and the acceptance of chronic kidney disease by patients. According to several studies, patients with a functioning kidney transplant demonstrate significantly higher levels of illness acceptance than those undergoing hemodialysis. Due to the rigorous and prolonged nature of dialysis treatment, as well as the lack of time for work, hobbies, and other social activities, hemodialysis patients often face increased social isolation and challenges in receiving adequate support [24].

Other researchers argue that chronic kidney disease reduces the scope of possibilities for physical activity, resulting in considerable dissatisfaction and a decline in quality of life in this area [25]. In the study by Piernikowska, most hemodialysis patients reported a moderate level of satisfaction with their quality of life. They tended to perceive their overall quality of life more positively than their personal health status [26].

Chronic kidney disease and its treatment methods have a significant impact on patients’ daily functioning. In long-term renal replacement therapy, improving quality of life is as important as life extension. future research should explore whether the implementation of illness perception-based tools could indeed enhance outcomes and quality of life in chronic kidney disease (CKD) [27,28].

Piotrowska et al. surveyed patients with peripheral arterial disease and found that the overall AIS-based illness acceptance score in the study group was satisfactory (fairly good), with a mean of 25.17 (SD = 0.85). The lowest level of illness acceptance was observed in the domain of self-sufficiency (mean = 1.68; SD = 0.64). Education and physical functioning had a significant impact on illness acceptance. An increase in life satisfaction was observed among patients who demonstrated greater acceptance of their illness [29].

Szcześniak et al. emphasized that, from a theoretical standpoint, their study broadens the understanding of the interrelationship between illness acceptance, sense of meaning in life, and well-being among adults with physical disabilities, as it is one of the few studies addressing this issue [30]. In the study by Wysocki et al., the mean AIS score was 27.44 (SD = ± 8.67). AIS results were positively correlated with perceived quality of life and health. Both AIS and quality of life (QoL) measures showed significant associations with selected socio-demographic variables (e.g., gender, age, education, and employment status) as well as clinical characteristics (e.g., type of treatment, duration of illness, or comorbidities) [31].

In their study of patients with multiple sclerosis, Dymecka and Gerymski found that illness acceptance is a significant mediator in the relationship between neurological disability caused by MS and health-related quality of life. Adaptation to the illness, as reflected in its acceptance, was found to be a better predictor of quality of life than disability itself [32].

Conclusions

Acceptance of a chronic illness affects the daily functioning of respondents, lowering their subjective assessment of health status and increasing their dependence on others.

Chronic diseases have a significant impact on patients’ self-esteem and sense of self-worth. Understanding these aspects is essential for providing comprehensive care that encompasses not only physical treatment but also emotional and psychological support.

POLSKI

POLSKI