Introduction

Population aging is one of the greatest challenges of modern medicine, and chronic pain affects a significant part of this population [1]. It is estimated that in the United States alone, bone metastases are diagnosed in over 400,000 people annually [2], while among oncology patients, the prevalence of pain reaches as high as 80% in advanced stages of the disease [3][4]. Osteoarthritis, in turn, affects more than 50% of people over 75 years of age [25], which further increases the scale of chronic pain problems among older adults. In this group of patients, pain leads to a significant decline in quality of life, reduced activity, and loss of independence [1].

Pharmacotherapy, based on the WHO analgesic ladder, remains the cornerstone of pain treatment, but its effectiveness is often limited due to multimorbidity, increased sensitivity to side effects, and numerous drug interactions [5][6]. In such cases, interventional techniques are gaining increasing importance, as they help reduce opioid use and limit their adverse effects [7][8][9]. Methods such as spinal analgesia [4], chemical and thermal neurolysis [9][10][11], spinal cord stimulation [18], or peripheral nerve blocks [12][13] have shown high effectiveness in managing pain resistant to systemic treatment, particularly in the elderly [16].

The aim of this paper is to discuss anesthesia methods and interventional techniques used in the treatment of chronic pain in elderly patients, with particular emphasis on cancer pain, neuropathic pain, and degenerative pain, as well as to analyze the safety, effectiveness, and potential complications of these procedures [16][17][18].

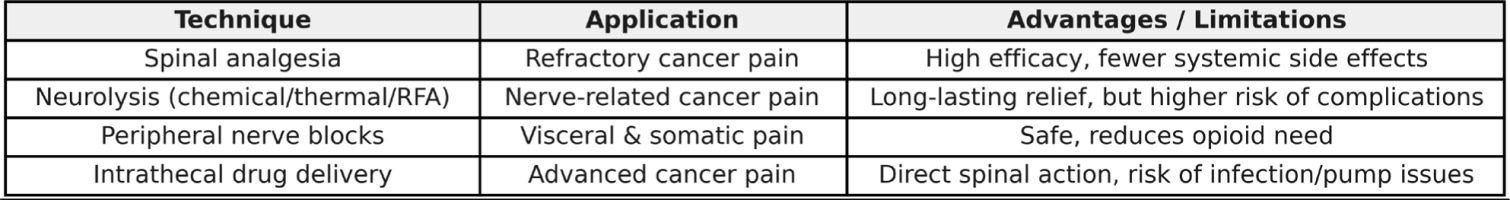

Table 1

Characteristics of anesthesia techniques used in clinical practice

Among elderly patients, cancer-related pain remains one of the most frequent and complex challenges. Therefore, the first part of this review focuses on interventional strategies specifically applied in cancer pain management.

Figure 1

Cancer Pain – Interventional Techniques. A comparative summary of interventional methods applied in cancer pain management among elderly patients.

Older adults (≥65 years) are commonly affected by a cancer diagnosis. The median age at the time of a new cancer diagnosis is 66 years, and the average age of death due to cancer is 72 years [1]. Bone cancer pain occurs particularly frequently in patients with advanced breast, prostate, and lung cancers. The prognosis worsens significantly once bone metastases appear. A large proportion of patients with metastatic bone disease experience moderate to severe pain. It has been shown that cancer-related skeletal metastases affect more than 400,000 people in the United States annually [2]. Tumor growth within bone tissue causes pain, hypercalcemia, anemia, pathological fractures, spinal cord compression, and reduced mobility, all of which contribute to a significant deterioration in functioning, independence, and quality of life for the patient.

Studies have investigated the expression and release of neurotransmitters and neuromodulators, such as galanin, as well as the regulation of macrophage activity and their infiltration, showing that tumor-related bone pain contains a neuropathic component, which may significantly influence the choice of analgesia and pain therapy [2].

Cancer pain is often so advanced and severe that conventional opioid therapy fails to provide adequate relief. In such patients, according to the WHO analgesic ladder, invasive pain control methods should be considered, such as neurosurgical interventions, subarachnoid neurolysis, or spinal analgesia.

A retrospective study [3] analyzing the medical records of all cancer patients receiving conduction anesthesia (spinal anesthesia in 44 patients or epidural anesthesia in 16 patients) at a single academic center over five years [3] showed that the most common indication for spinal anesthesia was pain resistant to systemic analgesics. After implementing anesthesia, good pain relief was achieved in 50% of patients in the epidural group and 70% in the spinal group. Based on this study, it was demonstrated that administering opioids into the spinal canal is an effective and safe method for patients with severe pain and may significantly reduce the need for systemic opioids [3].

High effectiveness of spinal opioid administration in refractory cancer pain has been demonstrated [4], and this route of administration also helps reduce the incidence of opioid side effects compared to oral administration [5]. Spinal analgesia shows greater effectiveness if a local anesthetic is added to the opioid [6]. In that study, most patients (83%) were able to reduce or discontinue systemic opioid use thanks to good or moderate pain relief with epidural or spinal analgesia.

One method of cancer pain treatment in older patients is neurolysis of nerves using radiofrequency ablation (RFA) [7][8]. Ablation techniques, including RFA that directly target the tumor, are increasingly used to relieve cancer pain. Another technique providing a longer pain-free period is neurolysis using alcohol or phenol; however, it is associated with a higher complication rate [9].

Subarachnoid dorsal neurolysis [10], involving the administration of alcohol or phenol into the subarachnoid space to destroy sensory nerve roots, is less frequently used nowadays due to its potential to cause serious side effects. Few studies support the choice of neurolytic agent, but alcohol may provide longer-lasting benefits compared to phenol. However, phenol requires a smaller volume and does not cause the intense burning sensation typical of alcohol [11].

In elderly oncology patients, interventional techniques such as peripheral nerve blocks should be particularly considered. Sympathetic fiber blockade, especially in visceral cancer pain, and intrathecal drug administration are among the most commonly used pain control techniques in this group [12].

A cohort study [13] involving 7,500 patients who underwent 43,000 facet joint nerve blocks showed that the most common complication of nerve block procedures was accidental intravenous injection of local anesthetic, occurring in 11.4% of patients, followed by local hematoma in 1.9%. Other complications, including vasovagal symptoms, severe bleeding, or significant nerve root pain and irritation, occurred in fewer than 1% of patients. These methods are particularly preferred in elderly patients because, in terms of side effects such as cognitive disturbances or systemic toxicity, they are safe and can significantly reduce the need for opioids.

When pain is not controlled with an oral treatment regimen, and further titration is limited by intolerable side effects, intrathecal drug delivery (IDD) provides direct access to the dorsal horns and their receptors. Importantly, implanted IDD systems are not a contraindication for MRI examinations or other oncological care, although pump failures have been reported shortly after radiation field exposure [14]. Randomized clinical trials demonstrated that IDD not only improves pain control but may also prolong survival by reducing the incidence of adverse events [15]. The most serious complication associated with intrathecal pumps is infection requiring explantation, occurring at a rate of approximately 3% [16].

In addition to opioids, bupivacaine, clonidine, or ziconotide can be administered intrathecally through the IDDS. In clinical practice, if a patient’s expected survival is three months or less, a tunneled epidural catheter with an internal port can be used, which may then be connected to an external drug infusion. For patients with a longer expected survival time, a fully implanted pump is preferred.

The most serious complication associated with the internal pump is infection requiring explantation, which occurs at a rate of 3% [16].

While cancer-related pain is often multifactorial and acute-on-chronic, elderly patients also frequently present with neuropathic pain syndromes. The following section explores interventional techniques dedicated to neuropathic pain.

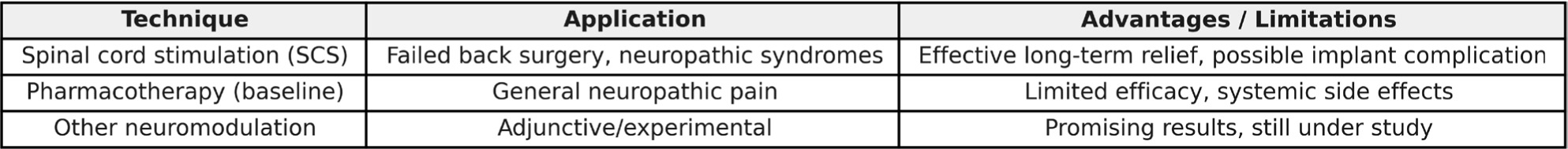

Neuropathic pain management in elderly patients

Figure 2

Neuropathic Pain – Interventional Techniques. Overview of stimulation and neuromodulation techniques compared with pharmacotherapy.

Chronic neuropathic pain is a type of pain that arises from damage to the peripheral and/or central nervous system [17]. It is characterized by sensations of burning, stabbing, tingling, and hyperalgesia — often described as “burning” or “electric” pain [17]. There are many mechanisms behind the development of neuropathic pain, including peripheral sensitization, meaning excessive excitability of nerve endings and increased spontaneous activity, as well as ectopic activity — where damaged nerves generate painful nerve impulses without a clear stimulus. Additionally, damage to the myelin sheath causes abnormal conduction of impulses through socalled ephaptic transmission (cross-talk between nerve fibers). Reduced activity of inhibitory systems — mainly decreased GABAergic interneuron activity — further facilitates pain conduction.

Neuropathic pain most often arises as a result of infection, trauma, ischemia, metabolic disorders, compression, radiation, or chemical factors [17]. The most common neuropathic pain syndromes among elderly patients include postherpetic neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy, peripheral neuropathies, phantom pain, complex regional pain syndromes, central pain, and spinal pain [17].

One of the techniques for treating this type of pain is neuromodulation. Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) is an advanced neuromodulation method used in chronic pain therapy, especially for neuropathic pain. Despite numerous studies, its exact mechanism of action is still being investigated. This therapy is used, for example, in patients with complications following neurosurgical procedures, such as failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS) or post-laminectomy syndrome.

The main indications include pain caused by compression of nerve structures (e.g., in the course of radiculopathy or plexopathy). During the procedure, the electrode is placed in the posterior part of the epidural space, adjusted to the location of the pain source. The impulse generator is implanted in the area of the upper gluteal quadrant, the anterior or posterior axillary line, or the abdominal wall near the costal arch.

A key element of the therapy is hyperpolarization of neurons induced by the anode (positive electrode), which allows modulation of nervous system activity [18]. Stimulation of large-diameter sensory fibers may block the transmission of pain impulses [19]. This results in increased GABA release and inhibition of glutamate release, which reduces neuronal excitability [20][21].

Studies confirm that SCS significantly reduces pain intensity in patients with chronic neuropathic pain. A 20-year review showed that over 70% of patients experienced a permanent pain reduction of more than 50%, particularly in postoperative syndromes such as FBSS [22]. Long-term observations indicate that SCS is a safe and effective method of treating pain resistant to conventional therapies [22].

Complications of SCS therapy include electrode migration (10–20%), infections (1– 5%), and transient paresthesias (2–4%) [22][23].

Beyond cancer and neuropathic conditions, a large proportion of elderly patients suffer from degenerative joint diseases leading to chronic pain. Consequently, the final section highlights interventional methods tailored to degenerative pain.

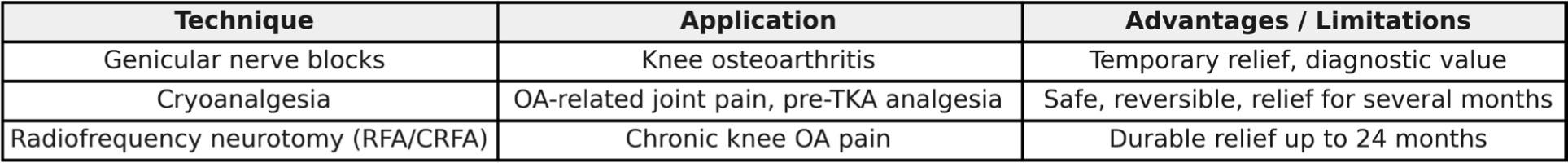

Management of degenerative pain in elderly patients

Figure 3

Degenerative Pain – Interventional Techniques. Comparative overview of interventional options for osteoarthritis-related pain in elderly patients.

Chronic pain affects approximately 20% of the global population, and in most cases, it results from musculoskeletal disorders [24]. Osteoarthritis (OA) affects a significant proportion of elderly patients. According to NHNS data, as many as 53.9% of patients in the United States over the age of 75 have been diagnosed with OA [25].

This disease is associated with joint inflammation and a progressive process of structural remodeling, which consequently leads to chronic pain [26].

Pain management is essential for improving patients’ quality of life and maintaining their daily physical functioning. Standard pain treatment is based on pharmacotherapy according to the WHO analgesic ladder, but the use of analgesics can be associated with numerous side effects and interactions with other medications. In patients with multimorbidity, this can create significant therapeutic challenges [27][28].

For this group of patients, it is crucial to use effective and minimally burdensome pain-relieving methods. In advanced stages of the disease, joint arthroplasty may be performed, but not all patients qualify for it due to their general health status or excessive body weight. In these cases, interventional anesthesia methods can be used either as a bridge therapy before surgery or as a standalone treatment [29][30].

Techniques other than oral pharmacotherapy used in pain management include cryoanalgesia, radiofrequency neurotomy, and sensory nerve blocks supplying the affected area. For the knee joint, these include genicular nerves, which are branches of the femoral, obturator, and tibial nerves. Interrupting the pain transmission through these nerves allows preservation of joint mobility while reducing pain symptoms. It should be emphasized that this does not affect the progression of the disease or the pathological remodeling of the affected joint.

The technique of blocking sensory nerve fibers conducting pain from the knee joint is usually performed under ultrasound guidance [31][32]. Genicular nerve block is a technique involving the administration of a local anesthetic to the sensory nerve responsible for pain conduction from the affected joint. The most commonly used anesthetic is bupivacaine combined with a glucocorticoid to reduce inflammation [30].

Studies have shown that this technique can effectively reduce pain for up to six months when using betamethasone with lidocaine, 50% alcohol with bupivacaine, or 99% alcohol with lidocaine [32]. It may also be used diagnostically to initially assess the effectiveness of subsequent neurotomy of these nerves with lidocaine [33].

Cryoanalgesia is a neurolysis technique using low temperatures — approximately 70°C [28]. The conduction block occurs via two mechanisms: cellular and vascular. The cellular mechanism is based on increasing osmolarity in the extracellular environment and sudden dehydration of Schwann cells, leading to demyelination along a segment of the nerve. The vascular mechanism involves constriction of vessels supplying the nerves and ischemia of the nerve-forming cells while maintaining the basement membrane, allowing the myelin sheath to regenerate within several months [28].

This procedure has proven effective in treating pain associated with knee osteoarthritis [28][34]. The use of genicular nerve cryoanalgesia before knee arthroplasty may also reduce postoperative opioid use for pain management of the operated joint [35].

Radiofrequency neurotomy (ablation) is a technique that uses radiofrequency currents to degrade nerve structures through ion heating. This method can be either conventional (RFA) or cooled (CRFA). The conventional technique operates at 80°C, while the cooled method uses 60°C [36]. These methods have proven effective in treating knee osteoarthritis pain [37][38]. CRFA has demonstrated pain relief in the knee for up to 24 months after the procedure [39].

Comparative Analysis of Interventional Approaches

When evaluating interventional techniques in elderly patients, several comparative observations emerge. Spinal analgesia remains the most effective method for refractory cancer pain, especially when systemic opioids fail. Neurolysis offers longer-lasting relief but carries a higher complication risk, making careful patient selection essential. SCS demonstrates the most consistent long-term outcomes for neuropathic pain syndromes, though device-related complications must be considered. For degenerative pain, particularly osteoarthritis, peripheral nerve blocks serve as both a diagnostic and therapeutic tool, while cryoanalgesia and radiofrequency neurotomy provide longer-lasting benefits with relatively low systemic burden. Intrathecal drug delivery, though invasive, is especially valuable in patients with multimorbidity and limited life expectancy, as it improves quality of life and reduces systemic side effects. A multidisciplinary assessment is crucial to balance efficacy with safety, particularly in frail geriatric populations.

Table 2

Comparative overview of interventional pain management techniques in elderly patients

Summary

Pain management in elderly patients requires a comprehensive approach that takes into account the specifics of the aging organism, multimorbidity, and the limited tolerance to the adverse effects of pharmacotherapy. In cases of refractory cancer, neuropathic, or degenerative pain, interventional pain management methods — such as spinal analgesia, neurolysis, spinal cord stimulation, or peripheral nerve blocks — represent an effective and safe alternative to systemic treatment. Their use enables better symptom control, reduces opioid requirements, and improves patients’ quality of life.

In the context of an aging population and the growing importance of palliative care, the development and dissemination of interventional techniques should be an important element of therapeutic strategies in pain management for the geriatric population.

POLSKI

POLSKI