Introduction

Currently, alloplasty is considered one of the most effective surgical techniques, relieving patients of pain and restoring joint function and proper alignment. The procedure involves excising the damaged or diseased joint and replacing it with an artificial acetabulum and head mounted on a stem inserted into the femoral shaft. The success of the procedure is influenced by many factors, including the patient’s general condition, preparation for the procedure, appropriate implant selection, postoperative wound care, rehabilitation, and patient self-care [1,2].

Self-care refers to the ability to initiate and perform activities aimed at maintaining health, managing symptoms, and restoring normal functioning. Assessment of self-care should therefore address the patient’s ability to implement self-care, including taking medications as prescribed, recognizing and managing symptoms, engaging in activities of daily living, and managing changes in health status [3]. Most clinicians believe that a patient should be discharged when their general condition is good, but this assessment is neither transparent nor uniform. The assessment of the required level of care, in other words, the basis for discharge, often remains poorly defined or poorly documented. The decision to discharge a patient from hospital is a complex process resulting from numerous factors, both medical and purely organizational, not all of which can be controlled. It is important to remember that pre-planned discharge improves targeted patient outcomes, quality of care, as well as logistical and financial issues for hospitals [4-6].

The aim of the study was to assess the readiness for discharge of patients after hip arthroplasty. wego.

Material and methods

The study was conducted at the Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology of the Musculoskeletal System at the Nicolaus Copernicus Hospital in Gdańsk, Poland, in 2023. Patients who had undergone hip replacement surgery were included. Consent was obtained from the management of the medical facility. Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. All respondents were informed of the purpose and nature of the study. The Bioethics Committee for Scientific Research at the Medical University of Gdańsk determined that the study raised no ethical concerns and did not require an opinion from the bioethics committee (KB/205/2025).

The inclusion criteria for the study were: obtaining verbal consent from the patient, being at least 18 years of age, being able to answer questions independently, and having undergone total hip replacement surgery to at least one hip. The exclusion criteria were: lack of patient consent, being under 18 years of age, being unable to answer questions independently, and having undergone total hip replacement surgery to another hip.

Twenty-six women and 17 men participated in the study. Respondents ranged in age from 37 to 93 years (x = 69.88, SD 13.84). The largest group consisted of patients aged 60-69 years (in the female group) and 70-79 years (in the male group). Urban residents predominated among the study participants (n = 34). Thirteen had completed secondary school, 11 had completed vocational school, 10 had completed primary school, and 9 had higher education. Eleven respondents were professionally active, 21 were retired, and 11 received a disability pension. Twenty respondents were married or in a civil partnership.

The study used a diagnostic survey method, a survey technique. The tool was an anonymous questionnaire containing a modified C-HOBIC scale for assessing readiness for discharge/therapeutic self care [3,7] as well as a patient’s metrics and questions enabling the analysis of experiences related to health education. The main part of the questionnaire included questions regarding knowledge about medications, which the patient should take after leaving the hospital, knowledge of the purpose of medication, ability to take medication as directed, ability to recognize symptoms related to the previous surgery, knowledge of what to do if symptoms related to the previous surgery appear, understanding medical staff recommendations (concerning the management of the operated limb, postoperative wound, dressing changes, anticoagulant therapy), ability to follow medical staff recommendations after leaving the hospital, knowledge of where to go/ what number to call in the event of an emergency/health deterioration, as well as who the patient should contact for assistance with daily activities (shopping, preparing meals, bathing), and the ability to move independently and perform daily activities. Respondents could select one of the following answer options: “definitely not,” “probably not,” “no, but I know who to consult,” “yes, but I have doubts,” “probably yes,” or “definitely yes.” A point scale was assigned to each answer to determine the degree of patient preparation for self-care: 0 – not prepared, 1 – poorly prepared, 2 – partially prepared, 3 – moderately prepared, 4 – well prepared, 5 – very well prepared.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis H test, and Spearman’s rho correlation (IBM SPSS Statistics 28 package). The significance level was p≤0.05.

Results

The highest level of preparation for discharge in the group of surveyed patients concerned knowledge about people who can provide assistance in performing daily activities (M=4.81; SD 0.70) and knowledge of potential sources of help in the event of health deterioration (M=4.28; SD 1.18), while the lowest level concerned the ability to independently perform daily activities (M=0.49; SD 1.01). Respondents’ indications in all assessed areas of self-care are included in Table 1.

Table 1

Basic descriptive statistics of the variables studied

The influence of sociodemographic factors

The analysis revealed that the willingness to be discharged from the hospital, as declared by the respondents, decreased with age in terms of knowledge of the purpose of taking medications, the ability to take medications as directed, awareness of possible postoperative symptoms, understanding of recommendations for caring for the operated body part, and the ability to independently perform daily activities (p≤0.05). A significant impact of respondents’ education on their declared self-care preparedness was also found. The higher the education of the surveyed patients, the greater their willingness to be discharged from the hospital in terms of knowledge of recommended medications, their purpose, and the ability to follow recommendations regarding their use, as well as awareness of possible postoperative symptoms, the ability to follow medical staff recommendations regarding care for the operated body part, and the ability to independently perform daily activities (p≤0.05). Details of the statistical analysis are included in Table 2.

Table 2

Influence of age and education on patients’ readiness for hospital discharge

The study did not confirm a significant influence of gender, professional activity and place of residence on patients’ indications, as both women and men, professionally active and inactive people, and residents of rural and urban areas assessed their readiness for discharge from hospital similarly – in all examined aspects (p>0.05).

The family situation of patients had a significant impact on the readiness for discharge, as it turned out that single people (compared to those in a relationship) assessed their preparation for discharge from the hospital worse in terms of knowledge of medications, the ability to follow medication recommendations and the procedure in the event of postoperative symptoms, as well as the ability to follow recommendations and knowledge of places to go in case of an emergency (Table 3).

Table 3

Influence of family situation of study subjects on readiness for discharge

The influence of factors related to hospitalization

The analysis revealed a number of statistically significant differences depending on the mode of admission to hospital. It turned out that patients admitted in a planned manner rated their preparation for discharge from the hospital higher in terms of knowledge of taking medications, understanding the purpose of taking them, and the ability to follow the instructions for taking them. They also declared greater awareness of possible postoperative symptoms, and also rated the level of understanding and ability to follow the instructions for handling the operated body part higher, had greater knowledge of places to go in case of an emergency, and rated their ability to independently perform daily activities higher (Table 4).

Table 4

Mode of hospital admission vs readiness of patients for discharge

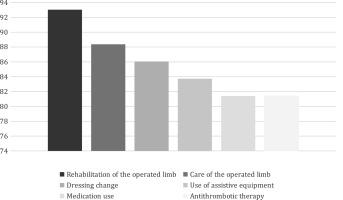

The most frequently involved person in the health education process was a rehabilitator or a physiotherapist (93.02%), followed by a doctor and a nurse (86.05% of responses each), and the least involved was a medical caregiver (6.98%). Most of the patients studied were informed about all important aspects of postoperative care. The least educated were those regarding anticoagulant therapy and medication use as recommended, while the most educated were those regarding rehabilitation of the operated limb (Fig. 1).

The most common form of health education used was instruction (93.02%), followed by individual conversation (88.37%), written instructions provided upon discharge from the ward (86.05%), and a talk (48.84%). Respondents did not report that ward staff used information brochures/leaflets or instructional videos. The analysis examined whether patients who rated the health education provided as sufficient, partially sufficient, or had no opinion differed in their level of preparation for hospital discharge. Significant differences were found between the compared groups in their knowledge of medications to be taken after discharge, their ability to adhere to medication recommendations, their awareness of possible postoperative symptoms, and their knowledge of the people providing assistance with daily activities. Details are presented in Table 5.

Table 5

Effect of satisfaction with health education on readiness for discharge

Discussion

Growing economic pressures have forced healthcare systems to reduce costs, prompting many hospitals to shorten hospital stays and, consequently, the time devoted to preparing patients for discharge. Many patients are discharged despite at least one barrier to discharge (e.g., lack of understanding of the treatment plan or inability to care for themselves without assistance). This approach generates a higher risk of adverse events. Therefore, assessing readiness for discharge is becoming increasingly important for ensuring patient safety, increasing satisfaction, and achieving better treatment outcomes and quality of care. A patient’s readiness for discharge is determined by a number of factors, including physiological status, knowledge, cognitive processes, availability of social support, and the healthcare system. A patient’s readiness for discharge is related not only to the amount of information the patient has received but also to individual factors. The patient’s current well-being, physical readiness, and emotional readiness have a significant impact on understanding the content being conveyed. Therefore, it is crucial to adapt the content and teaching methods individually to the patient’s abilities [4,8-11].

Assessing readiness should be a key element of the patient discharge planning process, as inadequate/ insufficient patient preparation often leads to negative consequences, such as inappropriate medication use, worsening outcomes, dissatisfaction with care, or rehospitalization. A useful tool for assessing discharge readiness is the C-HOBIC scale, which was used in our own studies. The scale allows for monitoring the effectiveness of patient self-care preparation [3,7].

One of the fundamental strategies for preparing patients for discharge is health education. Nursing staff, who have the most contact with patients, play a crucial role in this regard. The internally regulated standard in the ward where the study was conducted is to provide written instructions upon discharge and to teach patients how to manage the postoperative wound and change dressings. Patient education typically occurred during daily activities, which is associated with haste, difficulty assessing the patient’s needs, and a lack of tools for assessing the activities performed [12].

Our own research analysis revealed that patients had a relatively high level of knowledge regarding the use of recommended medications, which is consistent with the results of Kiłoczko and Grabowska’s study [13]. Respondents rated their ability to independently perform daily activities the lowest, which likely stems from the nature of the procedure.

Patients undergoing hip replacement require long-term rehabilitation, and mobility without assistive devices is often impossible in the first few days after the procedure. It is worth emphasizing that in none of the studies analyzed for this study, in which the authors used the C-HOBIC scale for assessing readiness for discharge, did respondents achieve such low scores compared to other areas of self-care. However, due to the specific nature of the procedure, the obtained results should not raise significant concerns. Patients participating in the study declared a high level of knowledge of places they should go to in the event of a health deterioration and of people they could turn to for assistance in performing daily activities. Similar results were obtained in the group of chronically ill patients by Andruszkiewicz et al. [14].

The analysis of our own research results shows that age significantly influences readiness for discharge. Similar observations were made by Bączyk et al., who found that patients over 60 years of age require more assistance in achieving full independence after intestinal fistula surgery [15]. Similar conclusions were drawn by Cierzniakowska et al., who, together with her co-authors, found that with age, patients undergoing surgical treatment for colorectal cancer experienced a decline in their daily functioning and an increased fear of discharge [16]

In our own research, no significant influence of gender and place of residence on readiness for discharge was found, which corresponds to the results of the study conducted by Derezulko and Grabowska in a group of patients after surgery [17], but is in opposition to the results of the study obtained by Kiłoczko [13].

Analysis of the results obtained in our own study revealed a number of statistically significant differences between patients admitted electively and emergency. Patients admitted electively rated their preparation for hospital discharge higher in almost every aspect examined. Derezulko [17] obtained different results in her study.

In summary, this study confirms the importance of evaluation in preparing patients for discharge after hip replacement. The C-HOBIC Discharge Readiness Scale is a useful tool for accurately assessing patient deficits and monitoring the effects of the self-care preparation process. Conclusions 1. The factors significantly determining readiness for discharge were age, education and family situation of the studied patients. 2. A significant influence of the mode of admission to the hospital and satisfaction with the performed treatment was found. in the health education department to prepare patients for self-care. 3. The C-HOBIC discharge readiness assessment scale is a tool that facilitates the discharge preparation process and enables monitoring of its effectiveness.

POLSKI

POLSKI