Introduction

Prostate cancer is being detected more frequently among men, leading to a corresponding increase in the frequency of performed radical prostatectomies. [1]. t is the second most common cancer in men worldwide, affecting approximately 1.1 million men annually [2]. Its incidence increases with age, and radical prostatectomy remains the gold standard of treatment for patients with organ-confined cancer with a life expectancy exceeding 10 years. However, it should be borne in mind that it is associated with many complications, including urinary incontinence, which significantly affects the quality of life of patients. For comparison, prostatectomy performed for benign reasons is associated with a urinary incontinence rate of 1%, while in the case of radical prostatectomy, this rate ranges from 2% to 66% [3]. Incontinence after the removal of the prostate (postprostatectomy incontinence) is the most common cause of male stress urinary incontinence. [4]. Ze względu na duży wpływ, jaki nietrzymanie moczu ma na jakość życia, konieczne staje się opracowanie strategii przyśpieszających rekonwalescencję. Due to the significant impact that urinary incontinence has on the quality of life, it becomes necessary to develop strategies expediting recovery. Considering that the age group most commonly affected by this issue is the elderly, surgical methods entail a higher risk of postoperative complications. Therefore, non-surgical interventions appear to be a safer solution. In this article, we will describe the role of pelvic floor muscle exercises (PFME) and their potential mechanism and effectiveness in the treatment of urinary incontinence after prostatectomy.

Purpose of the work

The aim of the article is to review the current state of knowledge on the effectiveness of non-surgical interventions, especially pelvic floor muscle exercises in the rehabilitation of urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy. We also considered alternative methods that may support the pelvic floor exercise protocol.

Materials and Methods

The article serves as a review of publications assessing the effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle exercises and other alternative methods in the rehabilitation and prevention of stress urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy. To achieve this, three databases were searched: PubMed, Google Scholar, and the Polish Medical Bibliography. To present current knowledge, we narrowed the publication timeframe to the years 2016 to 2023. Additionally, information on the anatomy of pelvic floor muscles, essential for a proper discussion of the topic, was derived from reputable Polish medical textbooks [5,6].

In order to determine the inclusion criteria, it was decided to include only publications that were published in 2016 or later and were included in the mentioned databases. Articles that did not meet these two criteria were excluded from analyses.

Results

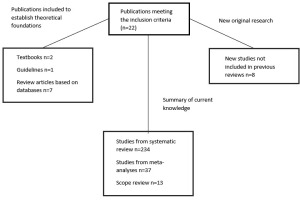

The study included 22 publications that met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). To determine the theoretical basis, information from two textbooks and The American Urological Association/Society of Urodynamics Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction Adult Urodynamics (AUA/SUFU) Guideline was used, and then from 7 review articles written on the basis of the literature available in databases.

Table I

Summary of Individual Rehabilitation Methods for Urinary Incontinence Post-Prostatectomy

In order to determine the state of current knowledge, 5 systematic review and meta-analysis articles were included, in which a total of 234 studies were analyzed as part of a systematic review, 37 studies as part of meta-analyses and 13 studies as part of a scope review. The summary was additionally expanded to include 8 randomized, retrospective or prospective studies that met the inclusion criteria.

Pelvic floor anatomy

The pelvic floor is formed by muscular and fascial structures, creating a strong closure at the bottom of the pelvic cavity through which the urethra, rectum, and vagina in women pass. The pelvic floor is bounded by the pubic symphysis, the apex of the sacrum, and both ischial tuberosities (the interspinal line), creating a rhomboid shape. The striated muscles of the pelvic floor form two partially overlapping plates. The upper, larger plate is the pelvic diaphragm. It has a funnel-like shape and is composed of the levator ani muscle and the coccygeus muscle. This is the upper layer of the pelvic floor muscles. The second, smaller plate is the urogenital diaphragm, consisting of the deep transverse perineal muscle and the external urethral sphincter muscle. It constitutes the middle layer of the pelvic floor muscles. Furthermore, there is a superficial layer that includes the ischiocavernosus muscle, bulbospongiosus muscle, superficial transverse perineal muscle, and the external anal sphincter muscle [5,6].

Pelvic floor physiology and consequences of its disorders

The pelvic floor, along with the bony pelvis, hip muscles, and gluteal muscles, provides support for internal organs and plays a crucial role in maintaining proper body posture [7]. oreover, the pelvic floor plays a significant role in ensuring proper bowel movements, normal sexual functions, physiological childbirth, and, crucially for the context of this article, maintaining control over urination [8]. Improper functioning of the pelvic floor muscles may lead to stress urinary incontinence. Abnormalities in the structure and support of the urethra and bladder neck by the pelvic floor muscles, as well as disturbances in the neuromuscular and mechanical function of the external urethral sphincter and levator ani muscle, which are part of the pelvic floor, appear to be associated with stress urinary incontinence (SUI) [9].

The urinary system is under the control of both the autonomic and somatic nervous systems, ensuring proper control of urine voiding. This control is also maintained by a group of muscles, including the detrusor muscle, internal sphincter, striated sphincter, and the puboprostatic ligaments. During radical prostatectomy, the proximal urethral sphincter and the puboprostatic ligaments are removed, resulting in a situation where only the striated sphincter becomes the primary element enabling urinary continence. During the procedure, there may also be damage to the neurovascular bundle and surrounding supportive structures of the urethra, resulting in an increased incidence of urinary incontinence after prostatectomy and difficulties in returning to normal functioning [10,11].

Risk factors for urinary incontinence after prostatectomy, as outlined in the AUA/SUFA guidelines, include advanced patient age, larger prostate size, and a shorter length of the membranous urethra (measured by magnetic resonance imaging) [12].

Pelvic floor muscle training

Pelvic floor muscle exercises or pelvic floor muscle training (PFME/PFMT) represent a non-surgical method for treating and preventing urinary incontinence after prostatectomy (as well as other types of urinary incontinence). It should be recommended to every patient immediately after radical prostatectomy, following catheter removal, to expedite recovery and restore normal continence [12]. Celem PFMT jest poprawa takich parametrów jak siła i wytrzymałość (strenght and endurance) mięśni dna miednicy a nawet zwiększenie przepływu krwi przez tkanki miękkie [13]. The goal of PFMT is to improve parameters such as strength and endurance of the pelvic floor muscles, and even enhance blood flow through soft tissues [13]. The precise mechanism of PFME remains a subject of discussion and has not been conclusively explained. It is believed that the primary mechanism involves an increase in the strength of the pelvic floor muscles, especially the levator ani muscle, which ensures the stability of the urethra and proper control of urine expulsion. Strengthening this muscle is achieved through conscious repetition of contractions of the anal sphincter, commonly known as Kegel exercises. The scope of pelvic floor muscle training doesn’t have to be limited to Kegel exercises alone; it can also include strengthening core muscles. This is based on the assumption that the contraction of abdominal muscles, especially the transversus abdominis, induces a reflexive co-contraction of the pelvic floor muscles. In addition to PFMT programs, a strategy called “the Knack” may be incorporated. This involves the conscious contraction of the pelvic floor muscles at the onset of a triggering factor for stress urinary incontinence, such as pre-contraction just before coughing, sneezing, laughing, or other activities temporarily increasing intra-abdominal pressure [14]. While it is challenging to find publications investigating the use of this technique in men after prostatectomy, it has proven effective in women with mild to moderate symptoms of stress urinary incontinence [15]. Therefore, conducting an assessment of the effectiveness of this technique in patients after prostatectomy could be valuable.

For pelvic floor muscle training to be conducted correctly, it is crucial to provide patients with proper education on how to perform the contractions. Education delivered by nurses both before and after prostatectomy has a significant impact on the recovery of urinary continence [16].

Efficacy of PFMT in people after radical prostatectomy

In the study by Milios JE et al., 97 men, aged 63 ± 7 years, who were scheduled for radical prostatectomy participated. The experimental group underwent intensive PFME training for 5 weeks before the procedure, which was continued for an additional 12 weeks post-radical prostatectomy. In contrast, the control group was advised to engage in low-intensity rehabilitation during the same period. The training for the experimental group involved the activation of both slow- and fast-twitch muscle fibers, achieved by performing six sets daily. Each set comprised 10 quick contractions (lasting 1 second each) and 10 slow contractions (lasting 10 seconds each) of the pelvic floor muscles, performed in a standing position. Therefore, each participant in the control group performed a total of 120 repetitions daily. The protocol employed by the control group included only three sessions per day, with each session consisting of ten contractions lasting ten seconds each, totaling thirty contractions throughout the day. At the beginning of the study, participants received instructions on performing contractions in a manner that allowed for adequate relaxation time. They were assessed before surgery and at 2, 6, and 12 weeks post-radical prostatectomy using 24-hour pads to measure urine volume, the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) questionnaire, the EPIC-CP questionnaire, and real-time ultrasound measurements to assess pelvic floor muscle function (RTUS). Individuals in the experimental group demonstrated a quicker return to normal continence and experienced fewer involuntary micturitions (leakage), as recorded by the 24-hour pads. They also showed a more dynamic improvement in IPSS and EPIC-CP questionnaire scores. Additionally, they exhibited better results in pelvic floor muscle function measurements using RTUS (faster repetitive muscle contractions - RRT index) compared to the control group [17]. Therefore, this study provides evidence that PFME improve pelvic floor muscle function and reduce post-prostatectomy incontinence. It is crucial to emphasize that, in addition to enhancing pelvic floor muscle function parameters, the improvement noted in the better scores on the IPSS and EPIC-CP scales indicates an enhanced quality of life for patients undergoing rehabilitation with PFME.

Pelvic floor exercises using resistance bands in individuals after radical prostatectomy have shown an improvement in the quality of life and a reduction in anxiety and depression symptoms [18]. Earlier studies, reporting similar results, also confirm that PFME are an effective rehabilitation method for urinary incontinence and should be recommended for all patients undergoing radical prostatectomy [19].

For the effective progress of rehabilitation involving PFMT, it is crucial for pelvic floor muscle contractions to be performed correctly. This means that the contraction should target the appropriate muscle group, and the duration of contraction and relaxation should be sufficient. Individuals who struggle with executing exercises correctly or have weak pelvic floor muscle contractions may benefit from the use of biofeedback. Biofeedback is a therapy involving specialized equipment that provides feedback on whether the patient is correctly performing contractions and relaxations through visual or auditory signals. It is often conducted under the supervision of a trained nurse or physiotherapist [20]. A meta-analysis by Hsu, Lan-Fang, et al., comparing PFMT with and without biofeedback, suggests that PFMT assisted with biofeedback exerts immediate, intermediate, and long-lasting beneficial effects in the context of urinary incontinence compared to PFMT without biofeedback when urinary incontinence was measured by objective indicators (e.g., pad weight). However, considering subjective indicators (number of incontinence episodes, number of pads used, subjective perception of incontinence severity), biofeedback had an additional effect only in the intermediate and long-term perspective. Additionally, there are indications that biofeedback has an additional positive effect on the quality of life of patients with urinary incontinence; however, the amount of data is too limited to make a definitive statement [21].

Alternative methods of rehabilitation support

In clinical practice, electrostimulation is utilized for pain management, muscle rehabilitation, and addressing motor function disorders. It is primarily employed as a treatment method for musculoskeletal system disorders. It has been demonstrated that its application in the anorectal region promotes hypertrophy and hyperplasia of muscle fibers, enhances collagen fiber production, and inhibits apoptosis. Electrostimulation has the potential to reduce the overactivity of the urinary sphincter muscle (detrusor hyperactivity) and serves as a predictive factor for restoring the strength of weakened muscles following prostatectomy [22].

Men experiencing urinary incontinence post-prostatectomy, subjected to electrostimulation in a protocol of 20 minutes per day, three days a week for 8 weeks, showed a better improvement in the frequency of urinary incontinence episodes, incontinence severity (assessed by a 24-hour pad test), treatment satisfaction (Likert scale), and quality of life improvement (IIQ-7 questionnaire) compared to those not undergoing electrostimulation rehabilitation [23]. Another study also demonstrated that electrostimulation combined with pelvic floor exercises (referred to as anus lifting exercises in the article) yields faster effects in the rehabilitation of urinary incontinence post-prostatectomy compared to exclusive PFME recommendations, although after a 10-week period, the effects of both protocols become comparable [24].

Electrostimulation is not the only method that can enhance the effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle exercise protocols. Acupuncture also demonstrates a potentiating effect on PFME. The mechanism of acupuncture in the context of urinary incontinence is not fully understood. One explanation could involve the inhibition of C-fibers, modulation of nerve growth factors, and reduction of spontaneous contractions of the detrusor muscle [25]. The implementation of a pelvic floor exercise protocol along with weekly acupuncture sessions may yield better treatment outcomes, resulting in reduced urine loss compared to rehabilitation solely based on PFME lower amount of involuntarily voided urine, as measured by the pad test, and a decreased usage of absorbent pads) [26]. However, a significant limitation in evaluating this method typically involves small study groups and a lack of uniform standardization of acupuncture procedures, emphasizing the need for research on larger cohorts [27].

Summary

Pelvic floor muscle exercises constitute an effective method for treating urinary incontinence post-prostatectomy. Although their mechanism is not fully understood, they lead to the strengthening of supportive structures around the urethra, primarily the anal sphincter. This ensures the stability of the urethra and proper control over urination. Improvement resulting from PFMT protocols occurs on both objective levels, such as a quicker return to normal continence and a reduction in involuntary micturition, and in the subjective well-being of patients, as indicated by survey results and observed decreases in anxiety and depression symptoms. This translates into an enhancement in the quality of life for patients. Moreover, incorporating additional supportive techniques into the PFMT protocol,such as biofeedback, electrostimulation in the anorectal region, or even acupuncture, may have a potentiating effect on therapy.

POLSKI

POLSKI