Introduction

In 2020, WHO inaugurated the 2021–2030 Decade of Healthy Aging as part of the International Day of Older Persons. The following program areas were distinguished: health protection, labor, social protection, and the demand for goods and services in education and housing. Particular attention was paid to the way of thinking and acting conducive to the active participation of older people in society and the provision of basic and long-term individually tailored healthcare services [1,2]. The analysis of the literature shows that there is no unambiguous threshold of old age. Traditionally, the elderly are defined as those over the age of 60 or 65. In 1913, the American sociologist Isaac Rubinow defined the age of 65 as the threshold of old age. More than 100 years have passed since this definition was introduced. In many developed countries, life expectancy has significantly increased, but people aged 65 or 60 are still considered elderly for statistical purposes [3]. In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) under the United Nations officially revised the age standards. According to the new age classification, the youngest-old, ages 60–75 years, middle-old, 75–90 years, and the oldest-old, ≥ 90 years [4]. In developed European economies, people aged 65 and over are considered elderly [5]. It is worth emphasizing that the definitions of old age are not consistent from the point of view of biology, demography, sociology or psychology [6].

Osteoporotic fractures are one of the basic problems of geriatric medicine. Analysis of data on osteoporotic fractures conducted in European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom and Sweden) has shown that the most common injuries were fractures of the proximal femur, including femoral neck and pertrochanteric fractures (PFs), vertebral compression fractures, distal forearm fractures, proximal humeral fractures ribs and tibia [7–9]. PFs are typically caused by a low-energy trauma such as ground-level falls. Despite the use of modern methods of osteosynthesis and comprehensive rehabilitation treatment, the consequences of pertrochanteric fractures are among the leading causes of disability resulting from dysfunction of the musculoskeletal system. PFs significantly reduce the quality of life and lead to loss of independence and impaired social functioning. Therefore, PFs need multidisciplinary prevention and treatment. One of the key points in the prevention of osteoporotic fractures in the elderly is raising health literacy. Numerous scientific studies indicate that a low level of health literacy correlates with increased mortality [10,11], longer hospitalization period [12], less frequent use of preventive health programs [13], irregular use of prescribed drugs [14], difficulties in communicating with health care professionals and poorer knowledge about disease processes and self-control skills among people with chronic diseases, including osteoarthritis [14,15].

Pertrochanteric fractures are not only an important medical problem, but also a social one, hence interdisciplinary cooperation on the border of sociology and medical sciences becomes necessary. Contemporary medical sociology finds its place in a wide problem area focused not only on the social aspects of medicine and medical practice, but also on health, disease and the human body. Actions in the field of preventive health care, one of the sub-fields of medical sociology, are increasingly based on the model of building health literacy among the society [16]. The concept of health literacy, functioning since the 1970s, is the ability to make decisions by an individual in the field of health in the context of everyday life, as well as in the perspective of functioning in society. The above definition, by Kickbusch and Maag, emphasizes the role of man as a consumer of health services. This consumer takes control over his own health, in particular, he has the ability to search for information about health and takes responsibility for decisions made in the area of health [16,17].

The aim of this study was to quantify observed strategies related to fall prevention and health literacy in a group of patients with pertrochanteric fractures treated with surgical fixation.

Material and methods

3.1. Subjects

A total of 70 patients, admitted to Central Clinical Hospital of the Ministry of Interior and Administration in Warsaw for pertrochanteric fractures between 2015 and 2019, at a mean age of 80.65 (range 75–99) were enrolled. Fracture osteosynthesis in 31 subjects was performed using the DHS method and in 39 subjects using the Gamma nail method. Between patients operated on with these two methods, there was no statistical differences in the sex and age distribution emerged. Eligibility criteria for inclusion: patients who had been operated by the same operator, DHS screw plate or intramedullary Gamma nail as a type of fixation used, age 75 and over, a minimum postoperative follow-up of 3 months. Criteria for exclusion: multi-site musculoskeletal injuries, pathological fracture (excluding osteoporosis). All patients after the fixation of PFs were subject to the same rehabilitation protocol. The study group, medical procedures performed, types of fixations, hospital stay and operation time were described in detail by the authors in a separate publication [18].

Each person involved in the study gave informed consent for inclusion before participating in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Medical Institute of the Ministry of Interior and Administration, Warsaw, Poland (protocol code 32, 13.02.2019).

3.2. Data analysis

Westmead Home Safety Assessment (WeHSA) Short Form is a comprehensive assessment designed to identify fall hazards in the home environments of older adults. It is an observational tool that provides a checklist of potential fall hazards. The checklist guides the examiner to supervise 14 general categories: external trafficways, general indoors, mobility aid, internal trafficways, living area, sitting, bedroom, footwear, pets, bathroom, toilet area, kitchen, medication management, safety call system. Each categories has a series of questions to encourage the examiner to watch for potential fall hazards. WeHSA also include history of falls, functional vision and cognition, mobility, home and community supports/ assistance. The assesment was performed approximately three months after surgery in a home visit [19].

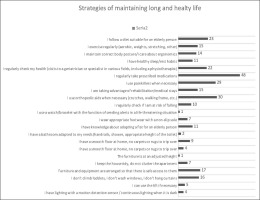

The medical interview with the patient was extended with data from the authors’ own questionnaire regarding the causes and location of the injury, and the sociological part, which consisted of strategies used by patients to maintain a long and healthy life. The questionnaire form can be found in the appendix to the article. Strategies for maintaining a long and healthy life were divided into three categories. The first category concerned the patients’ habits, such as: following a properly balanced diet, following the recommendations regarding physical activity, adopting a body position in accordance with the principles of ergonomics, and observing sleep hygiene. The second category related to the health-promoting behavior of patients, including regular check-ups with specialists, taking recommended medications, using rehabilitation treatment and auxiliary equipment (e.g. crutches, props), being especially careful when exposed to a fall, using with the function of sending alerts in a life-threatening situation, using appropriate footwear to prevent slipping. The third category of strategies applied concerned the prevention of falls at home. This category included both issues related to the respondents’ knowledge of adapting the apartment in terms of the changing needs of an elderly person, as well as specific actions aimed at preventing falls, such as having an appropriate bathroom, floor, furniture, lighting, spatial arrangement, keeping order and avoiding potentially dangerous household activities. Data were collected during follow-up visits, and patients were asked to tick the option they agreed with or the statements included in the questionnaire were read by the researcher and the subject responded whether he or she agreed with them or not. The questionnaire was performed three months after surgery.

3.3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with Statistical software—Statistica 10.0 working on Windows 10 (StatSoft, Cracow, Poland). The data were normally distributed, as tested by the t-test for independent sample tests. Data with a distribution inconsistent with the normal (plantar pressure distribution in masked regions of the foot) were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U Test. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses.

Results

The Westmead Home Safety Tool Short Form was administered to 70 people, including 12 people who agreed to the study being conducted at their place of residence, and the remaining 58 people answered the questions during a follow-up visit to the clinic. Among the people surveyed, 26 questionnaires were completed in full, in the remaining cases partial answers were obtained. A summary of the most important results, where n - number of residents confirming the presence of the most common fall hazards was greater than or equal to 5 (n ≥ 5), is presented in table 1 below (Table 1). All results are presented in the supplementary material.

Tab. 1

The list of residents with the most common fall hazards assessed using Westmead Home Safety Tool Short Form within three months after surgery. The results show the number of respondents who agree with the following statement (n > 5, short version)

The study conducted using the authors’ questionnaire showed that dominant cause of injury was a ground-level fall in the place of residence, respectively 52 test subjects in all group. The direct cause of the fall was a trip/slip, respectively 43 subjects in the study groups gave such an answer, as well as fainting, 13 persons. Among the direct causes of falls, dizziness was also distinguished, respectively 10 responses in the study group.

Discussion

Injury prevention is a very important and underestimated element of healthy aging. Low-energy fractures, including pertrochanteric fractures, caused by falling due to slipping or tripping in one’s own home have become the main cause of injuries among older people [20]. According to Zhu et al. hip fractures accounted for 58,3% of all fractures [21]. Based on the literature review the mortality rate is up to 30% in the first year after the pertrochanteric fracture [22].

The research we have conducted shows that 74.3% (54 from70 patients) of all fractures occurred in the patient’s home, which has been also confirmed by the results of Zhu et all research [21]. Taking into account the fact that the leading cause of the accidental fall in the analyzed group was a trip/ slipping, preventive actions aimed at raising health literacy and unifying the commonly used criteria for evaluating risk factors for falls related to the home environment seem to be a priority. The analysis of the results obtained using the WeHSA Short Form showed that the apartments inhabited by older people are largely unsuited to their changing needs and capabilities, especially the bathroom and toilet area. Eliminating potential obstacles and proper arrangement of apartments significantly increases the safety of older people [20].

The study draws attention to the fact that a small percentage of respondents take specific actions to maintain a long and healthy life. Only about 15% of the surveyed people have knowledge about the possibility of adapting the apartment in terms of the changing needs of the elderly, and few people take preventive measures, both pro-health habits and specific actions aimed at reducing accidental falls.

Based on the analysis of the survey results, it can be assumed that the elderly, in addition to the deficit of knowledge about the risk factors of falls, have difficulties in implementing specific strategies aimed at maintaining a long and healthy life. Only 21% of people in surveyed group confirmed that they systematically use rehabilitation programs and treatment stays, while 14% of the respondents checked the risk of falling. The results obtained in the project confirm the existing problem in the appropriate adaptation of flats in terms of the changing needs of the elderly. Only 2 people from the entire study group have an adapted bathroom, the lack of carpets and rugs, posing a potential tripping hazard, was found in 7 people. Four people from the 70-people surveyed group have adapted room lighting. It should be noted that only 1 person from the entire study group had a system of calling for help in a life-threatening situation. Numerous scientific studies indicate that unsuitable floors (presence of thresholds, carpets and rugs, lack of non-slip mats) [23], unsuitable bathroom and toilet (without handles and handrails) [24,25], insufficient lighting [25,26], protruding elements that can be tripped over, as well as incorrect height of furniture and household appliances [23] contribute to falls [27,28]. Research conducted by Rasu et al. confirms that a high level of health literacy shortens the length of hospital stay and reduces the frequency of using medical services [29]. The level of health literacy is influenced by demographic and socio-cultural factors such as social status, education, employment, income level, culture and language. This awareness is also shaped by one’s own experiences related to the disease, the health care system, individual characteristics of a person, such as: age, sex, race, or the ability to think analytically [21].

Injuries of the musculoskeletal system in the elderly are among the diseases that significantly generate the costs of long-term care due to the growing process of population aging [20]. According to data from the Central Statistical Office in Poland, current expenditure on health care for 2021 amounted to PLN 169.4 billion, which represented 6.4% of GDP, including 8.1% of the costs of long-term health care [30]. Tailored policy for healthy aging, increasing health literacy and injury prevention, can effectively reduce the need for long-term care, thus contributing to lower expenditure on care service delivery, which belongs to the fastest growing social expenditure in Europe [31].

Treating prophylaxis as the most optimal method of treatment, it seems legitimate to state that quick diagnostics including functional assessment and the risk of falls, as well as appropriately applied preventive measures will allow for more effective prevention of falls in the future [20]. One of the potential opportunities to introduce preventive measures is an action similar to that proposed by WHO in the case of ensuring perioperative safety. In 2009, WHO introduced the “surgical safety checklist”. It is a simple survey, currently operating all over the world based on simple questions allows to reduce the number of surgical errors. The use of similar algorithms to improve the safety of the elderly could reduce the number of falls and thus the number of surgical interventions [32,33].

Demographic and socio-cultural factors were not included in the survey questionnaire due to limitations resulting from the possibility of the respondent to focus on a limited number of questions asked. Elderly patients, often with numerous comorbidities and at the same time communication limitations - visual impairment, hearing loss, difficulties in expressing themselves and formulating coherent statements, are exposed to problems related to the lack of effective communication. With increasing age, there is a weakening of cognitive functions, which can be considered physiological and natural for the aging process. In the elderly, the selectivity and concentration of attention are also weakened, and the reaction time to stimuli is prolonged. There may be difficulties asking the right questions or giving answers, losing the thread of the conversation, synthesizing information, or getting tired of the conversation. Answers given to too many questions, at least by some of the respondents, may be unintentionally falsified [34-36]. Although the study group consisted only of 70 people and the results cannot be certainly applied to the entire population of middle-old and oldest-old patients, it can be assumed that people with a low level of health literacy do not attach due importance to health prevention, which is confirmed by the fact that the leading direct cause of a pertrochanteric fracture was a ground-level fall in their own apartment due to tripping/slipping.

Conclusions

The majority of falls in the elderly population stem from inadequate housing adaptations. This necessitates systemic institutional strategies to advance senior-centered environmental design principles.

Older adults predominantly prioritize post-fall therapeutic management over primary prevention strategies. This necessitates evidence-based educational campaigns integrating standardized fall risk assessments and proprioceptive training protocols to enhance postural stability.

Effective fall prevention requires intersectoral cooperation, i.e. integration of medical, social and engineering activities, mainly architectural (e.g. environmental consultations, building modifications).

POLSKI

POLSKI