Introduction

Diabetes is undoubtedly one of the most prevalent and serious lifestyle-related diseases, often referred to as the first non-communicable epidemic. In the modern world, the aetiology of this condition is largely associated with civilisation-related factors, including changes in lifestyle such as the consumption of processed food and reduced physical activity. In recent years, the number of patients living with diabetes worldwide has risen significantly (six-fold), and mortality attributable to diabetes and its complications reaches up to 5 million annually. It is estimated that in Poland approximately 2.5 million individuals suffer from diabetes, some of whom remain undiagnosed (1). For this reason, early detection, prevention, and appropriate management are of paramount importance. This encompasses dietary interventions (including weight reduction), increased physical activity, and pharmacotherapy (2).

Equally vital is patient education, aimed at preparing individuals to actively participate in the therapeutic process. Educational interventions directed towards both patients with diabetes and their caregivers constitute one of the key components of contemporary models of diabetes care. Effective diabetes education enhances the likelihood of preventing complications, thereby improving patients’ quality of life and prolonging survival (3,4).

The principal objective of therapeutic measures in the management of diabetes is to equip patients and their families with the skills required for effective self-management, conscious collaboration with the multidisciplinary care team, and the maintenance of self-discipline. The effectiveness of diabetes care depends on numerous factors, among which the competence and experience of the therapeutic team play a crucial role. An interdisciplinary and highly qualified diabetes care team consists not only of physicians and nurses, but also dietitians, physiotherapists, and diabetes educators. Nurses, who spend the most time in direct contact with patients, must therefore possess up-to-date clinical knowledge enabling them to provide effective education. Regular training, specialist courses, and self-directed learning in diabetology are essential for the success of educational and therapeutic interventions. Well-prepared nurses are able to convey essential information and provide professional nursing care for hospitalised patients with diabetes. Continuous knowledge updates and the acquisition of new skills form the foundation of lifelong learning, which is one of the core obligations of the nursing profession and a vital element of medical practice in the management of diabetes (4–6).

It is widely recognised that diabetes, particularly type 2 diabetes, is one of the most prevalent chronic conditions and constitutes a major burden on public health worldwide. Regardless of type, diabetes requires intensive and continuous self-monitoring, which entails patients adopting new roles and responsibilities crucial for disease management. The burden of diabetes extends beyond increased morbidity and mortality; it also encompasses reduced quality of life, affecting physical and mental health, social interactions, and environmental factors. The demand for self-discipline in managing the condition frequently induces psycho-emotional stress. Moreover, many patients experience fear of both short- and long-term complications resulting from poor glycaemic control. Consequently, psychological distress may develop, negatively impacting quality of life. Psychiatric or psychosocial problems, in turn, may disrupt self-management and adherence to treatment, significantly complicating or even impeding effective diabetes care. Such patients pose a substantial challenge for diabetes care teams and require an individualised therapeutic approach that integrates medical, nursing, psychological, and even social support, despite routine evidence-based diabetes care pathways (4,7–11).

Integrated diabetes care interventions aim to improve glycaemic outcomes, reduce stress, and enhance social functioning in individuals affected by the disease. For this reason, it is imperative that nurses providing diabetes care possess comprehensive knowledge and the full range of skills necessary to support patients in managing their condition effectively, thereby contributing to improved health outcomes and quality of life.

The primary aim of this study was to analyse the nursing responsibilities involved in the care of hospitalised patients with diabetes. Numerous factors influence the effectiveness of such care. One of the key objectives of the study was to highlight the nurse’s role in monitoring blood glucose levels. In addition, the study sought to demonstrate the importance of nursing in educating patients and their carers regarding self-management of diabetes, including the performance of self-monitoring of blood glucose, insulin administration, and adherence to dietary recommendations (12). Parallel objectives included evaluating the contribution of nursing care to the psycho-emotional status of patients, particularly in supporting them to accept the disease (13,14).

The intention of the study was to provide a comprehensive understanding of the role of nursing care in the therapeutic process and in the management of patients with diabetes. The study attempted to assess the impact of nursing practice on improving patients’ quality of life, emphasising a holistic approach to health and well-being in the context of diabetes management (11).

Material and Methods

The research material was obtained through a diagnostic survey. The applied research technique was a questionnaire, and the research tool consisted of an original survey questionnaire. The questionnaire comprised a demographic section and a general section. Additionally, two standardised instruments were employed from the ‘Health Behaviour Inventory’.

Health-related quality of life associated with health behaviours was assessed using the standardised Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) (15). A five-point Likert scale was applied, where the highest score represented the greatest level of health-related burden, and the lowest score indicated the least burden. The second standardised tool utilised was the Self-Care of Diabetes Inventory (SCODI), which consists of 40 questions (16,17). In this case, a five-point scale was also employed, with the highest score reflecting the most consistent performance of daily behaviours applicable to individuals living with diabetes, and the lowest score denoting the least engagement in such behaviours.

The study focused on nursing tasks undertaken in the care of hospitalised patients with diabetes. The survey was conducted between March and May 2025 during a period approved by the Bioethics Committee (approval no. KB/PIEL–II27.2025). Questionnaires were distributed to patients in accordance with GDPR regulations, and completed forms were collected in person. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study, its anonymity, and the voluntary nature of their involvement. Using the observation method, which involved systematic monitoring of patients’ functioning in their daily environment, the information obtained from the questionnaire was verified through direct observations of their health status. The selected group was not very large due to the short duration of the research but close observation allowed for the selection of representative study population.

The survey was carried out among patients admitted to the hospital’s Department of Internal Medicine. The obtained results were subjected to statistical analysis using the χ2 test for independent samples. A 5% margin of error was adopted, and a probability value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

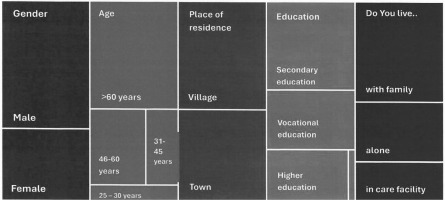

The demographic data relevant to the analysis of patients with diabetes are presented in Table 1 and illustrated graphically in Figure 1.

Table 1

Sociodemographic structure of the subjects (N = 50)

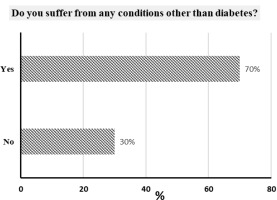

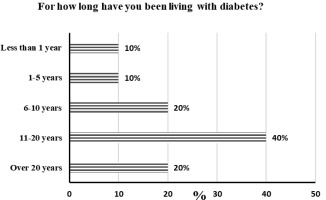

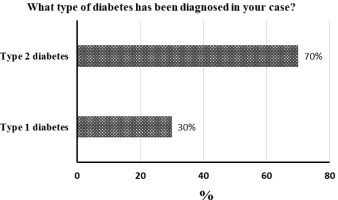

The distribution of responses to the items included in the original survey questionnaire are illustrated graphically in Figures 2-14.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of responses to question no. 1 “Do you suffer from any conditions other than diabetes?” Thirty-five respondents (70%) reported different conditions in addition to diabetes, while 15 participants (30%) indicated no coexisting conditions.

Figure 3 shows the distribution of responses to question no. 2 “For how long have you been living with diabetes?” Twenty participants (40%) had been living with diabetes for 11–15 years, 10 participants (20%) for 6–10 years, another 10 participants (20%) for more than 20 years, 5 participants (10%) for 1–5 years, and 5 participants (10%) for less than 1 year.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of responses to question no. 3 “What type of diabetes has been diagnosed in your case?” Thirty-five respondents (70%) reported type 2 diabetes, while 15 participants (30%) indicated type 1 diabetes.

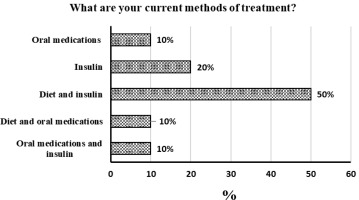

Figure 5 shows the distribution of responses to question no. 4 “What are your current methods of treatment?” Twenty-five respondents (50%) reported combining dietary management with insulin therapy. Other responses included: 10 participants (20%) treated solely with insulin, 5 participants (10%) with oral hypoglycaemic agents, 5 participants (10%) with diet and oral medication, and 5 participants (10%) with a combination of oral medication and insulin.

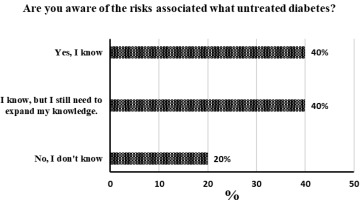

Figure 6 shows the distribution of responses to question no. 5 “Are you aware of the risks associated with untreated diabetes?” Twenty respondents (40%) reported awareness of the risks of untreated diabetes, 20 participants (40%) declared the need to expand their knowledge in this area, and 10 participants (20%) stated they were unaware of the potential consequences.

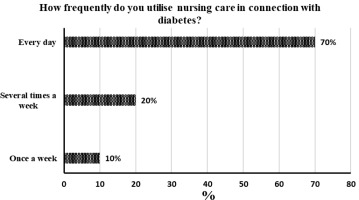

Figure 7 shows the distribution of responses to question no. 6 “How frequently do you utilise nursing care in connection with diabetes?” Thirty-five respondents (70%) reported daily nursing care, 10 participants (20%) indicated several times per week, and 5 participants (10%) reported once per week.

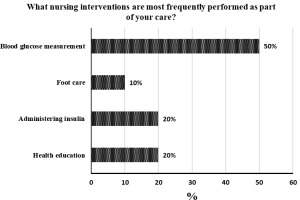

Figure 8 shows the distribution of responses to question no. 7 “What nursing interventions are most frequently performed as part of your care?” Twenty-five respondents (50%) reported that the most common nursing activity was blood glucose monitoring, whereas the least frequent was foot care (5 participants, 10%). Insulin administration and health education were each reported by 10 respondents (20%).

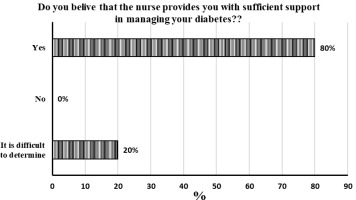

Figure 9 shows the distribution of responses to question no. 8 “Do you believe that the nurse provides you with sufficient support in diabetes care?” Forty respondents (80%) reported adequate support from nurses in diabetes care, while 10 participants (20%) indicated difficulty in assessing the level of support.

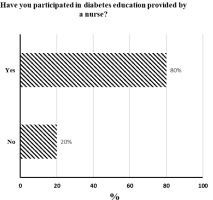

Figure 10 shows the distribution of responses to question no. 9 “Have you participated in diabetes education provided by a nurse?” Forty respondents (80%) confirmed participation in nurse-led diabetes education, while 10 participants (20%) reported no such involvement.

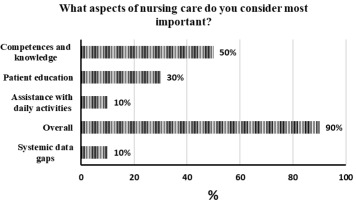

Figure 11 shows the distribution of responses to question no. 10 “Which aspects of nursing care do you consider most important?” The majority of respondents (25 participants, 50%) identified nurses’ competence and knowledge as the most important aspect of nursing care. The least important was assistance with activities of daily living (5 participants, 10%). Other responses included education (15 participants, 30%), while 5 participants (10%) provided no data.

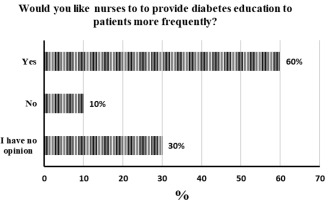

Figure 12 shows the distribution of responses to question no. 11 “Would you like nurses to provide diabetes education to patients more frequently?” Thirty respondents (60%) stated that they would like nurses to educate patients more often. Five respondents (10%) reported that they would not want more frequent education, while 15 participants (30%) had no opinion on the matter.

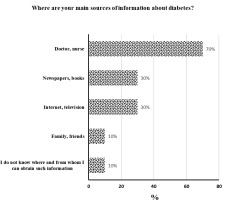

Figure 13 shows the distribution of responses to question no. 12 “What are your main sources of information about diabetes?” The majority of respondents (35 participants, 70%) indicated that they obtained knowledge about the disease from physicians and nurses. Additional sources of information included the press and books (15 participants, 30%), as well as the internet and television (15 participants, 30%). The least common sources were family and friends (5 participants, 10%), and uncertainty regarding where or from whom to obtain information (5 participants, 10%). Note: multiple answers were permitted for this question; therefore, the total percentage exceeds 100%.

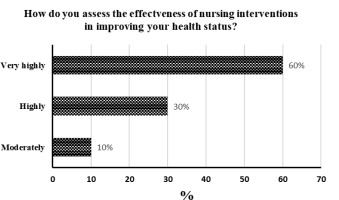

Figure 14 shows the distribution of responses to question no. 13 “How do you assess the effectiveness of nursing interventions in improving your health status?” The majority of respondents (30 participants, 60%) rated the effectiveness of nursing interventions as very high. A further 15 participants (30%) assessed them as highly effective, while 5 respondents (10%) indicated moderate effectiveness.

Of particular concern is the proportion of respondents (20%) who answered “No, I do not know” to Question 5 – “Are you aware of the risks associated with untreated diabetes?”. This finding is closely related to the responses to Question 9 – “Have you participated in nurse-led diabetes education?”, in which 10 respondents (20%) answered “No”.

Table 3

Distribution of responses to questions 13–18 from the standardised Self-Care of Diabetes Inventory (SCODI).

Based on mean scores, the highest rating was given to attention paid to symptoms of abnormal glycaemic levels, such as increased thirst, frequent urination, weakness, or excessive sweating. The mean score was 4.1 with a standard deviation (SD) of 0.83, indicating a high level of consistency among nurses in this area. Regular blood glucose monitoring received a mean score of 3.5 (SD = 0.35), reflecting relatively frequent performance of this task. Recording blood glucose values in a logbook was rated at 2.9 (SD = 0.64), while systematic blood pressure monitoring scored 2.8 (SD = 0.64), suggesting that these activities were performed moderately often. Lower scores were reported for daily foot monitoring (mean 2.4; SD = 0.84), indicating insufficient regularity despite its importance in preventing diabetic complications. The lowest rating was given to regular body weight monitoring (mean 2.2; SD = 0.94), suggesting this activity is rarely undertaken by nurses.

In summary, nurses paid the greatest attention to clinical symptoms indicative of glycaemic disturbances, while the least emphasis was placed on daily foot monitoring and body weight control.

Table 4

Distribution of responses – Self-Care of Diabetes Inventory (SCODI).

| Lp. | SELF-CARE OF DIABETES INVENTORY – SCODI) | N | Min | Max | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Health behaviours | 50 | 33 | 48 | 39,4 | 4,8 |

| 2 | Health status monitoring | 50 | 20 | 34 | 24,4 | 3,8 |

| 3 | Blood glucose monitoring | 50 | 24 | 31 | 27,5 | 2,3 |

| 4 | Self-confidence | 50 | 32 | 43 | 36,3 | 3,3 |

Among the 50 patients studied, the highest mean score was observed in the domain of blood glucose monitoring, with a mean of 27.5 points and a SD of 2.27. This indicates a relatively high and consistent level of engagement in glycaemic self-monitoring. The second-highest domain was self-confidence in diabetes self-care, with a mean of 36.3 points (SD = 3.32), suggesting that patients reported moderate-to-high confidence in their ability to manage the condition independently. Health-promoting behaviours achieved a mean of 39.4 points (SD = 4.83), indicating greater variability in the extent to which respondents engaged in general health-related behaviours. The lowest mean score was recorded for overall health monitoring (24.4 points; SD = 3.84), which may reflect insufficient patient engagement in the systematic monitoring of various health aspects beyond glycaemia.

In summary, patients demonstrated the strongest performance in blood glucose monitoring and displayed relatively high self-confidence in self-care activities, while their weakest results were observed in overall health monitoring.

Table 5

Distribution of responses – Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) Questionnaire.

The vast majority of patients (90%) reported a moderate level of emotional distress associated with diabetes, highlighting the need for in-depth dialogue with healthcare professionals and, where appropriate, psychological support. Only 10% of respondents demonstrated a high level of distress, which may be indicative of more severe emotional difficulties and the necessity for referral to specialised psychological or psychiatric care.

The findings suggest that although most patients do not experience extreme levels of distress, as many as 9 out of 10 individuals report emotional difficulties significant enough to warrant the attention of the therapeutic team.

Table 6

Distribution of responses to item 8 in the Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) Questionnaire.

In this study, 87.5% of respondents who rated nursing support as adequate reported a moderate level of emotional distress, while 12.5% reported a high level of distress. Among patients who answered “difficult to say”, all (100%) experienced a high level of distress. Statistical analysis using Pearson’s chi-square test did not reveal a significant association between the perceived adequacy of nursing support and the level of emotional distress (χ2 = 1.38; p = 0.238). This indicates that the subjective evaluation of nursing support did not have a statistically significant impact on the emotional stress levels of patients with diabetes.

Table 7

Distribution of responses to Question 9 in the Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) Questionnaire

Among patients who participated in nurse-led diabetes education, 87.5% reported moderate emotional stress, while 12.5% reported high stress. Among those who did not participate in such education, all (100%) experienced only moderate stress. Statistical analysis using Pearson’s chi-square test revealed no significant relationship between participation in diabetes education and emotional stress levels (χ2 = 1.38; p = 0.238). This indicates that participation in nurse-led education had no significant impact on the severity of emotional stress in the study patients.

Table 8

Distribution of responses to Question 8 in the original survey questionnaire

Patients who perceived nursing support as adequate achieved higher mean scores in the following self-care domains: health behaviours (M = 50.00; SD = 5.18), health monitoring (M = 24.50; SD = 4.02), blood glucose monitoring (M = 34.50; SD = 2.43), and self-confidence (M = 35.38; SD = 2.68). In contrast, participants who responded “difficult to say” demonstrated lower mean scores: health behaviours (M = 29.25; SD = 3.16), health monitoring (M = 24.00; SD = 3.16), blood glucose monitoring (M = 20.50; SD = 1.58), and self-confidence (M = 40.00; SD = 3.16). The Mann–Whitney U test confirmed statistically significant associations between perceived nursing support and the overall level of self-care. These findings suggest that patients’ subjective evaluation of nursing involvement in diabetes care has a significant impact on the extent to which self-care behaviours are undertaken.

Table 9

Distribution of responses to Question 9 in the original survey questionnaire

This analysis compared the level of self-care between patients who participated in nurse-led diabetes education and those who did not (Table 10). Among participants in education, the mean scores were as follows: health behaviours (M = 38.75; SD = 4.55), health monitoring (M = 24.88; SD = 4.10), blood glucose monitoring (M = 27.25; SD = 2.47), and self-confidence (M = 36.75; SD = 3.35). In the group that did not participate in education, higher mean scores were recorded for health behaviours (M = 42.00; SD = 5.27) and blood glucose monitoring (M = 28.50; SD = 0.53), while lower scores were observed for health monitoring (M = 22.50; SD = 1.58) and self-confidence (M = 34.50; SD = 2.64). Although some differences between groups were observed, the Mann–Whitney U test showed that they were not statistically significant (Z = 3.83; p = 0.056). This indicates that participation in nurse-led diabetes education did not have a clear, statistically significant impact on the level of self-care behaviours among the patients studied.

Discussion

This study analyses various aspects of nursing care provided to hospitalised patients with diabetes, including both core clinical issues and psycho-emotional dimensions.

The findings demonstrate that nurses focus primarily on clinical manifestations, particularly disturbances in blood glucose levels, while paying less attention to daily foot monitoring and body weight control. Glycaemia, especially in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of diabetes, remains the principal indicator of disease progression, and its measurement constitutes a routine element of health monitoring. However, the prioritisation of routine measurements risks marginalising other indicators that are equally significant in disease progression. On the other hand, the emphasis on strict glycaemic monitoring, as other authors also show, reflects nurses’ vigilance towards life-threatening complications and highlights this area of practice as a priority in daily nursing care [ 18, 19].

The results also confirm that the educational role of nurses is essential in supporting patients’ self-care behaviours and optimising their ability to manage life with a chronic condition. Nurses’ motivation and professional attitude directly influence the level of patients’ self-care, underlining the importance of holistic care and the need to strengthen nurses’ communication and educational competencies. Similar findings have been reported by other authors, who have shown that intensive health education contributes to improved clinical outcomes, including a reduction in hyperglycaemia in patients with type 2 diabetes (20). These observations are supported by further evidence indicating that patient education and an individualised, interdisciplinary approach are crucial for effective therapeutic outcomes and for improving the quality of life of patients living with diabetes (20). The findings also suggest that individuals with diabetes present higher levels of health-promoting behaviours, which may be an outcome of education provided as part of chronic disease management. This interpretation is consistent with research conducted by Z. Juczyński and coauthors, who demonstrated that patients with diabetes achieve the highest scores in the “Health Behaviour Inventory” compared with individuals with other chronic diseases (21, 22).

In our study a significant association was observed between nursing support and patient’s emotional stress levels. This is not surprising because other authors have shown that diabetes can cause negative emotional reactions known as diabetes-related mental disorders (DRD) (23). In addition to that, the stress associated with this disease mainly relates to the anxiety and fear that accompany living with diabetes and the burden of self-monitoring (24).The high prevalence of moderate emotional distress among patients with diabetes (90%) observed in the present study may reflect the considerable psychological burden of living with a chronic condition. The fact that 9 out of 10 patients reported moderate emotional distress highlights the need for structured supportive conversations and psychoeducational interventions as part of standard diabetes care. It seems that such measures may help prevent the escalation of emotional problems and contribute to improved treatment outcomes. Therefore, a detailed assessment of diabetes-related stress should be carried out by a qualified diabetes education team to help patients cope with their emotions, enabling them to take a more balanced approach to living with disease (23, 24). Although, the presented results show that, distress levels were not extreme, their prevalence constitutes a serious warning sign for healthcare teams. Among 10% of respondents, high levels of emotional distress were identified, suggesting deeper psychological difficulties and the need for referral to specialised psychological or psychiatric care. These findings strongly confirm the necessity of a holistic approach to diabetes management, integrating both somatic and psychological care. Chronic emotional stress may negatively affect treatment adherence, glycaemic control, and overall quality of life, making psychological support an integral component of effective diabetes therapy. The present study indicates that the therapeutic team and particularly nurses, who have the most frequent contact with patients play a crucial role in recognising urgent problems and responding appropriately to patients’ emotional needs. They also confirm the need to continue this type of distress research, with a particular emphasis on collaboration between mental health professionals, primary care nurses, and family doctors in the care of patients with chronic diseases (25).

Given the multifaceted challenges faced by patients with diabetes and their expressed needs, healthcare provision must adopt an interdisciplinary approach with strong emphasis on comprehensive nursing care. These findings, consistent with reports from the literature, emphasise that nurses’ involvement and objective clinical assessment are key to effective patient education, psycho-emotional support, and the overall success of the therapeutic process (12, 25). The present results also confirm once more, just like the others (26), a collaborative healthcare model is much more beneficial for improving patient satisfaction with care and for the development of harmonious nurse-patient relationships.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that priority nursing interventions are primarily focused on glycaemic monitoring. While this reflects vigilance towards immediate health risks, it may lead to the marginalisation of other important aspects, such as regular foot examinations.

The psychological burden associated with diabetes highlights the need for emotional support and the implementation of structured psychoeducational interventions.

Nurses’ involvement, professional competence, and communication skills significantly influence multiple dimensions of the therapeutic process, substantially enhancing its effectiveness. As the healthcare professionals in closest and most frequent contact with patients, nurses play a central role not only in identifying somatic problems but also in recognising psycho-emotional difficulties.

The findings confirm that an individualised approach, incorporating diabetes education and addressing both somatic and psycho-emotional aspects, contributes to improved therapeutic outcomes, including glycaemic control and health-promoting behaviours.

In summary, effective diabetes care requires an interdisciplinary model in which nurses play a pivotal role in supporting physicians and psychologists, ensuring both clinical oversight and psychological support are integrated into the therapeutic process. However, this assumption should be treated with caution due to the relatively small number of respondents. It’s worth to emphasise that our data are still preliminary and need to be verified by further research.

ENGLISH

ENGLISH